Fergus McGinley

In this follow-up to his previous and provocative article, “Do the heavens declare the glory of God?”, Fergus McGinley critiques “scientific ideology” and attempts to retrieve the soul.

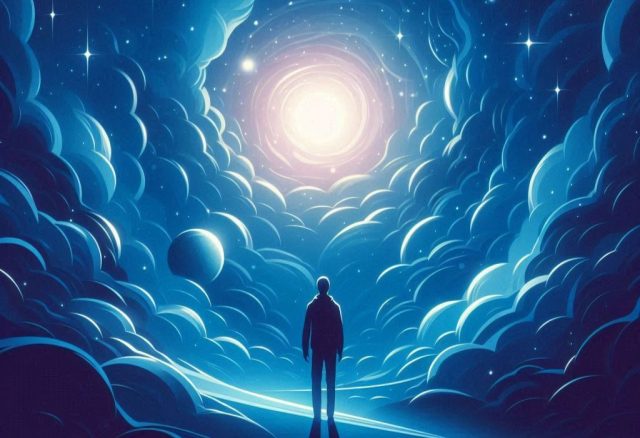

If you read my previous opinion piece in these hallowed pages,[1] you’d know that I just don’t buy the idea that “the heavens declare the glory of God” (Psalm 19). As much as I try, when I look up at the night sky I don’t see the beauty and charm and thrill of the planets and the Milky Way; rather I see the endless, heartless void of the material cosmos, coming from nowhere in particular (the so-called Big Bang), and going nowhere very nice at all (eventual universal heat extinction). It is the ruthless, totalitarian scientific laws of nature I see, writ large, in the night skies, not the benevolent hand of the Creator; in a word, death, not life.

Yes, now that human technological and scientific development has chased the soul out of the world, there’s no way back, I’m sorry to say, to the worldview of the ancients. Never again, presumably, will God be the Spirit in the Sky, and never again will we imagine chariots ascending into the heavens, or try to glean meaningful life lessons from the ever-changing configurations of the celestial orbs.

It’s the soul thing that’s really the most painful, the most demoralising. We might have been able to cope with science disappearing the soul from the heavens, the earth and the seas, the rocks and trees and animals; even, heaven-forbid, with science deleting God himself—the great Soul of the World – from the picture. But the one it really hurts to let go of is our own soul—yours and mine.

Because, according to the latest scientific theories, you and I are not living souls, but bundles of neurons, synapses and brain-waves, beeping away in material brains, ultimately controlled by their own biochemistry and at the mercy (not that they’ll show any) of genes and environment. Welcome to the Zombie Apocalypse, I reckon. For when we cut loose our own souls in the name of scientific correctness, what else do we become but zombies—bodies wandering around without souls, with no real living agency to animate them, just a dumb urge to act as if life is actually meaningful? God help us.

Francis Crick, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, put it pretty baldly when he said:

You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of identity and free will are in fact no more than the behaviour of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.[2]

God help us, indeed; and God save us from such zealots.

But surely there must be some way back from the brink of this particular abyss? Is there any chance, we might venture, that we can prevail upon science to give us back our souls? Let me regale you with a few hopeful, if wacky, thoughts in this direction.

The scientific worldview is just plain false

There’s one very significant misconception we need to deal with for starters. The scientific worldview is just plain false. I’m not talking about science itself—wonderful, beautiful, useful, reliable, marvellously objective science, our go-to problem-solving toolkit any day of the year for just about every practical problem our species comes across—rather I’m talking about science as ideology, science supposedly explaining the world.

Science certainly does explain a whole lot of things. It explains how technologies and all sorts of practical processes work—everything from computers and motor cars, to plant breeding techniques and genetic engineering, minerals extraction, vaccinations and chemotherapy. You name it, science doesn’t just explain it, it more or less creates it. Yes, science explains a million and one things we can do to the world; but it does not, and cannot, explain the world itself.

Shock-horror. You’re thinking that this is a pretty well-kept secret I’m letting you in on. But the prime cause of science’s inability to explain the world is down to the very method it employs, the much-vaunted scientific method. The central MO of the scientific method is an active, controlled, material intervention in pre-existing reality. There is no sitting around waiting for reality to do something off its own bat; rather science, quintessentially, acts. It is material cause and effect, action and reaction, stimulus and response, from start to finish. The scientist pokes reality then observes how it responds. What is observed in a scientific experiment, therefore, is not reality itself, but how it responds to our pokes. This, in a nutshell, is why science can’t explain the world.

It doesn’t matter whether the intervention by science is direct—you accelerate bits of matter up to insane speeds in a particle accelerator then fire them at a vanishingly thin metal foil target—or indirect—you artificially set up and control conditions of observation in, say, an experiment to observe animal behaviour. Either way, what’s never really observed, what is just not observable at all in this way, is pre-existing reality itself. Reality is sitting there, hidden in plain sight, behind or beyond (or before) the scientific observations. There’s no doubt it exists; it’s just that science can never get its hands on it.

This fundamental limitation of science, and of human perception in general, has been pointed out endlessly in the history of philosophy. It is the age-old problem of the noumena versus the phenomena—reality versus appearance. It is the observer paradox, the theory-ladenness of observation, even the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. Every attempt to develop a simple representation theory for scientific truth founders on this point. There is no way out of it; science cannot represent, cannot explain, the world.

No big fizz for science itself, of course. Science goes on its merry way, being without doubt the most useful, reliable practical tool humans have ever invented. It’s the never-ending packet of Tim Tams, the gift that keeps on giving. But using science to explain the world? That’s another matter altogether, fraught with peril, bound to fail.

The world of science is really a virtual world, linked to the real world not by representation but by action. It comes alive—becomes actual—only when we apply it. We humans love building virtual worlds. Cyberspace, the internet. The many worlds of literary fiction, of film, of art generally. Systems of government, social and economic institutions. The ABC and the AFL. The world of the soul—thinking, memory, imagination, dreaming—is a beautiful virtual world; in fact the original virtual world, the one from which all other virtualities flow. Nothing wrong with virtual worlds; well, nothing necessarily wrong. What’s great about science, qua virtuality, is its link to the world of everyday experience through material action. It is a wonderfully fecund schema of potential material action, ever growing, ever being refined. It doesn’t explain the world; rather it does something much more useful: it changes it.

Save our souls

Now what has all this got to do with getting science to give us back our souls? Well, just about everything. As Francis Crick says, people believe science has somehow proved the soul doesn’t exist. We’ve fallen for this hook, line and sinker. We all think the soul is a metaphor, or perhaps a “theological category” (as opposed to a scientific one). More fool us. Because science has absolutely not proved the soul doesn’t exist, not even remotely. All science has done is search for material techniques for influencing the soul—influencing human behaviour, consciousness, mind, whatever you want to call it. The biological, genetic, biochemical, physical, etc. determinants of the mind or soul are not determinants at all. Rather they are material means for influencing, changing, modifying, interacting with the soul.

The soul itself is beyond the reach of science. Why? Because the soul can’t be directly controlled by any material cause. Because the soul itself is not material. Because the soul is a self-cause; that is, it causes itself. It is free agency, pure and unalloyed, ultimately autonomous. We can use other words for soul like “self,” “persona,” “spirit,” “mind,” “consciousness,” “I” and so on, but they are all at root the same one thing: an immaterial agency or volition which can’t be directly controlled by any sort of material, external cause and basically causes itself.

Obviously soul is influenced in all sorts of ways by external causes. It is stuck in a physical body for starters, which puts all sorts of demands and constraints on it. Then there are the physical and social environments which hem it in on every side. But at the centre of soul—and this is true for all living things, plant or animal—there is a free living agency, a thing (not a material thing) which causes itself; which, at a deep and irreducible level, is master of its own destiny.

I hope you’re breathing a sigh of relief. We’re not zombies after all! The philosophers have been pointing this out since forever; it’s only in the twentieth century with the rise of scientific ideology that people have been silly enough to think that the soul mightn’t be real. It’s the cogito of Descartes, the conatus of Spinoza (and others), the élan vital of Bergson, the will to live of Schopenhauer, the struggle to survive of Darwinism, the will to power of Nietzsche, even the autopoiesis of Maturana and Varela. And of course it’s the central character of every religious tradition under the sun. But whatever you want to call it, it’s staring you right in the face, every minute of every day.

Before and after science

Now we’ve got our souls back, we can return to the heavens. What do they look like through this post-scientific lens? Well, actually more like they used to look to the ancients, interestingly enough. Scientific cosmology imagines a virtual eternity and infinity of materiality, mostly empty space with a few (zillion) pin-pricks of matter, coming (as I have said) from nowhere in particular and going nowhere very nice at all. But there is one big thing missing. Yes: soul. The missing piece of the puzzle, the most important piece of the puzzle.

Really, once you realize that science can’t explain the world, and that, despite all the bad press, the soul is really real, all bets are off. What the world is, where it came from and where it is going to, simply cannot be accounted for by science in any way. These are open questions once again, and science has no more of a say, in fact much less of a say, than the great human traditions of philosophy, art and (heaven forbid) religion, which we always looked to in the past.

So what does philosophy say, what does art say, what does religion say, about the heavens? Try something like this:

The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands.

Day after day they pour forth speech; night after night they reveal knowledge.

They have no speech, they use no words; no sound is heard from them.

Yet their voice goes out into all the earth, their words to the ends of the world. (Psalm 19: 1-4)

Sounds pretty good to me.

What we are looking at, when we take our scientific goggles off, is a universe with soul. The universe has produced, somehow, both mind and matter, operating in tandem, with a marvellous symbiosis (though not always mutually beneficial), one not reducible in any way to the other. When we look out at the night sky, therefore, what we see is not merely an endless, merciless, material void, but a living cosmos; one in which we sense, in spite of (or perhaps because of) its apparent immensity, a real connection with us as individuals—a soul-to-soul connection. This is certainly what the psalmist felt so keenly back in the day, and it is also, very certainly, what we can still feel today. There’s something out there, something alive and real and profound; I don’t know what it is, but I sure can’t wait to find out.