Do the heavens declare the glory of God? Fergus McGinley wrestles, in this provocative opinion piece, with the scientific understanding of a cold pitiless universe that perhaps does not “declare the glory of God.” We welcome responses to this article.

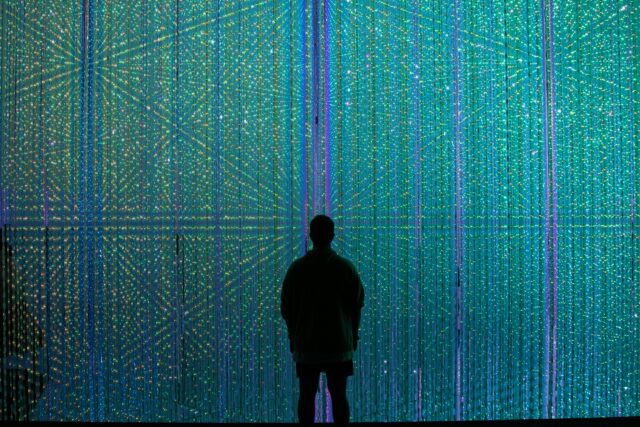

Recently, we’ve been treated to the wonderful ABC TV Series Stargazing Live, featuring our very own Julia Zemiro (legendary compere of RocKwiz), the scarily talented (if foul-mouthed) Tim Minchin, and Britpop boy-astronomer, Professor Brian Close, among a veritable galaxy of space-experts. How we marveled at spectacular views of the solar system from the Siding Springs Observatory, even grander pictures of deep space from the Hubble Space Telescope, dramatic computer-generated simulations of stellar and galactic evolution, not to say the homespun DIY-astronomical charms of quirky Greg Quicke (Space Gandalf), from out back-of-Broome. The world of outer space is without doubt marvelous, breathtaking, beautiful, full of hope and promise; the final frontier no less.

And you know there’s even a cast-iron biblical warrant to all this. Long before Julia, Tim, Brian, Greg et al. cottoned onto it, the great psalmist himself noticed something slightly glorious about the heavens. In Psalm 19—everyone’s favorite celestial psalm—David boldly testifies:

“The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands.” (v. 1).

The night sky, apparently, has God’s name written all over it.

But no, a thousand times no!

For starters, the modern scientific view of the heavens is absolutely not friendly, awesome, beautiful; in fact, it is hostile, totally scary, the worst nightmare you ever had. And secondly, anyway, the ancients, including the psalmist, had a completely different view of the cosmos, one which is utterly at odds with the modern scientific worldview.

Just think about it. The heavens, on our current scientific view of the universe, are a virtual infinity of dead empty space. Sure, there might be billions of stars out there, but they’re all so far away from each other and from us, that as big and mighty as they might be, the dread emptiness of empty space trumps them a billion times over. Sure, there’s a vague chance, a snowflake’s chance in hell, that there might be a planet or two, somewhere, sometime, around one of these billion suns, that might sustain life, might have already produced it. But fat chance of us ever finding that out, let alone interacting with those fellow life-forms in any way whatsoever.

And it’s only going to get worse. It’s a one-way ticket to oblivion. The stars, the galaxies, are just getting further and further apart, Hubble’s famous constant assures us. Matter, energy, everything is being dispersed, stars are burning out, raging futilely against the dying of the light. In the end there’ll be so much nothing, that even a zillion galaxies won’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy old universe. Science declares it with an authoritarian flourish: the heat death of our puny universe, unwitting victim of that cruelest and most tyrannical of all laws, the fabled Second Law of Thermodynamics. God help us.

I’m running out of hyperbole. Of course, it all looks beautiful and charming when we look up at the night sky at the brilliance of the Milky Way from the comfort of our earthly station (when we’re out happily camping far from the city lights, or having a lovely night out with the kids at the local observatory). But if we were actually out there beyond the safety of the atmosphere we’d be dead in an instant before plummeting back to earth, burning up in the atmosphere along the way. Most of us feel the sheer terror of it when we go flying, even if it’s only for a moment before we put it out of our minds and keep watching the in-flight movie. What even greater terror there must be, space-walking, hanging by a thread, from the International Space Station. Let alone on Apollo 11, floating in a tin can, desperately, with Houston faintly calling, trying to make it back to Planet Earth.

And of course it all looks awesome and amazing from the comfort of our sofas, when we’re watching Stargazers Live, or the latest sci-fi film, showing the wonders of space with the latest computer graphic imagery, accompanied by fabulous classical music. But that’s the music, the CGI, the comfy sofa speaking. Really imagine yourself out there, amongst it, just for one instant, and you’ll turn to stone, regret you ever turned on the telly in the first place. Martin Amis put it pretty succinctly when his narrator in God’s Dice, mulling over the contradictions of his London neighbor, the enigmatic Bujak, muses:

“Staring up at our little disc of stars (and perhaps there are better residential galaxies than our own: cleaner, safer, more gentrified), I sensed only the false stillness of the black nightmap, its beauty concealing great and routine violence, the fleeing universe with matter racing apart, exploding to the limits of space and time, all tugs and curves, all Hubble and Doppler, infinitely and eternally hostile.”

Yes, there is only an infinitesimal slice of this universe that is not absolutely hostile to human life. It’s a virtual infinity of instant death. If you don’t believe me, here’s what’s written beside the model astrolabe on top of the dam wall at Mt Lofty Botanic Gardens in Crafers, part of an interpretive trail set up for visiting kiddies to read (God help the poor little darlings):

Life on earth is only possible because of stars.

Almost every element of earth was made inside a star.

We feed off energy provided by our star, the sun

And one distant day we will be consumed by it.

But what about Psalm 19; surely that will give us some succor? Unfortunately, no. Remember that David was writing circa 1000 BCE. In those days we still lived in a geocentric universe. The sky, the heavens, apart from being the home of all sorts of pretty celestial orbs, were where God and the angels resided. Hence the prophet Elijah was translated into heaven in a chariot of fire by a whirlwind. He wasn’t going to the after-life, but to the heavenly present-life with God, promoted straight from human to angel, so to speak.

So, no wonder the heavens looked good to the ancients. There was a real sense in them of a return to our true home, our true source. They were awesome, friendly, meaningful. Millennia of astrologers extracted all sorts of interesting and useful life lessons from them.

But now we know better. We’ve got scientific goggles on. Astrology is just silly pseudo-science, and God and the angels no more reside in the heavens than do Ra, Zeus, Ahura-Mazda or the Big Chicken in the Sky. If we still want to cling on to some belief in an after-life, it’s in Heaven—presumably a sort of parallel spiritual universe—not The Heavens. Modern science seems to have managed to banish everything cute, cuddly or heavenly from the heavens forever, leaving it mostly a dead nothingness.

So what, you say. Even if the heavens are a lifeless infinity, what matters is that, either way, God created them. That is enough. They’re beautiful, they declare God’s glory, end of story. If God wants to create a universe which is more or less completely hostile to human life, that’s God’s business—who are we to interpret it in a negative way? And even if we do start asymptoting off into a universal heat extinction event, presumably Jesus will return in the nick of time and save the day, the ultimate deus ex machina.

Well, maybe. The problem is that this view sounds plausible only if you’re already a believer; only if you’re already committed to interpreting the world as created by God, regardless of how different it might look now, through scientific eyes, compared to how it looked in Bible-days. You’re ever ready with the ad hoc fix, the disclaimer that it will all make sense when Jesus returns, so don’t worry about trying to make sense of it now. But this will never convince modern Westerners, who’ve been brought up on a steady diet of all-saving science and God-skepticism. It will just confirm the fact that things are as they seem to be: you’re just making it up as you go along.

There’s a real impasse here, a fatal clash between science and Christianity. And at the moment it looks more like it’s going to be fatal for Christianity. The fact of the matter is that the scientific view of the world is utterly soulless. Humans don’t have souls; animals and plants sure don’t. And the Soul of the World (i.e., God)?—you really are nuts. Doesn’t matter whether you are looking on the super-micro or super-macro level, there is no soul to be found anywhere in this material, scientific world. Just matter, lots of empty space, maybe a bunch of fields. Not so much as a whisper of soul.

The ancients by contrast found soul everywhere. Deluded they surely were, but they were the same ones who thought the heavens declared the glory of God. In those animistic days everything was alive and had meaning—the heavens, the rocks and trees, the earth and the seas, the animals, even humans. The story of human history is the story of the rise of science and technology, and the gradual de-animation of the world. It was de-animate or perish, really: in order to effectively control the hostile material conditions of life, one just has to treat those material conditions (the heavens, the rocks and trees, the earth and the seas, the animals, even humans) as if they had no soul. For soul has agency, and it is precisely that external agency which ever threatens you.

Here’s the crux of the argument in fact. It is we human souls, we human agents, who have driven soul from the world. We have won material control, even world domination, but the price we have paid is to sell our own souls to the devil (so to speak). Delicious irony.

So, no, the Heavens surely don’t declare the glory of God, not any longer anyway, not through the scientific eyes we moderns are doomed to view the world with. The worldview of the ancients, of the psalmist himself, is no longer accessible to us. We and him look at the night sky and see different things: he a living, meaningful cosmos, we a dead, soulless infinity. Is it a crying shame—the end of religion, the end of God, the end of life as we knew it? Or is it worth the prize we have won in its place: beautiful science and wonderful technology? You decide.

As for Stargazers Live, we’re not going to stop loving Julia, Tim, and Brian (well, maybe not Tim and Brian), and we’re not going to stop being mind-boggled by the visual beauty of the stars, but I don’t know where the terror’s going to go. As dear old Ishmael muses in Moby Dick, waxing lyrical about the dread whiteness of the great leviathan:

“Is it that by its indefiniteness it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation, when beholding the white depths of the Milky Way?” (Chapter 42)

Let’s just hope our future voyages into deep space don’t suffer the same fate as the Pequod.