Chris Mulherin originally presented this talk at the MST Paradosis Conference, held 9–10 August 2024.

It is a great pleasure to offer this “taster” tonight as we launch into what will surely be a worship-inspiring exploration of creation and the God who we know as Creator. After all, whatever we think about origins and creation, in the most profound sense of the word, Christians are all “creationists” because we worship the one who we affirm as Creator of all things and the ultimate origin of all that is.

In these opening comments about “integrating our knowledge of origins,” I want to offer some takes on creation and origins, some takes on science and faith and the relationship between them. And also some takes on why Christians ought to engage robustly with science and technology. We will only integrate our knowledge of origins if we come to peace with science.

“In the beginning was the Word.” The universe owes its origins and continued existence to the creator God revealed most fully in Jesus Christ. Creation is not just an event in deep-time history. For thoroughgoing theists and especially Christians, the doctrine of creation affirms that there is a sustainer-God upholding life, the universe and everything.

And, for centuries, some Christians, who were known as “natural philosophers”—and now, more recently as “scientists”—have understood themselves to be exploring and revealing the hand of the Creator as they do their science. In fact, it was not until 1833 that an Anglican clergyman by the name of William Whewell first called such people scientists.

Another word, invented by a group of Australian scientists some forty years ago, was an awkward one. Despite the efforts of people like me, that word has not come into common use. I am thinking of the word or acronym “ISCAST.”

In 1987 a group of Jesus-following scientists from the Research Scientists’ Christian Fellowship set up the Institute for the Study of Christianity in an Age of Science and Technology. That is definitely a name designed by boffins, so today we prefer the tagline, “Christianity and Science in Conversation.”

From students to eminent scientists as well as theologians and philosophers, ISCAST brings together Christians who are interested in God’s creation and the knowledge and questions that science and technology raise. Our senior members are the fellows, three of whom have won the Prime Minister’s Prize for Science. One of our overseas fellows is Jennifer Wiseman, who works for NASA and is the senior project scientist on the Hubble Space Telescope; you’re probably familiar with some of Jennifer’s snaps.

Let me tell you something about why a fellowship of people around the country might enjoy thinking and writing and meeting together around science and faith. And, in the bigger picture, why have Christians, historically, engaged in science and connected science with the theological doctrine of creation?

Why should Christians engage with the technoscientific enterprise?

1. Because science reveals the hand of the Creator

Firstly, Christians should engage with technoscience because science reveals the hand of the creator.

The history of Christians doing science, and indeed the history of the scientific revolution, is a history of understanding science as revealing the hand of the Creator. Francis Bacon was a Christian who did so much to give us the foundations of science as we know it.

In 1605, Bacon published The Advancement of Learning in which he formalised a metaphor that Christian scientists have used for centuries. It’s the metaphor of the two books of God. Bacon says that God has two books—the book of his word and the book of his works—Scripture and science. So, science, understood this way, reveals the hand of the Creator and draws us to God.

It’s ironic that Bacon’s words appear opposite the title page of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species, which is perhaps the most famous example of so-called conflict between science and faith. Darwin chose to use Bacon’s affirmation of the importance of both science and faith.

To conclude, therefore, let no man out of a weak conceit of sobriety, or an ill-applied moderation, think or maintain, that a man can search too far to be too well studied in the book of God’s word, or in the book of God’s works; divinity or philosophy; but rather let men endeavour an endless progress or proficience in both. (Bacon: Advancement of Learning)

I won’t read out Bacon’s original words. Instead, my paraphrase, with a nod to Douglas Adams and the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, is this: “Be sure to study both God’s word and God’s world. Both science and Christianity help us to know the truth about life, the universe and everything.”

2. Because technology fulfils the creation mandate

When we take the knowledge of science and use our God-given creativity, we become co-creators with God. This is the heavy responsibility given to humans in the image of God: the responsibility to use our creative gifts for good and not for evil.

This is part of the outworking of the so-called creation mandate of Genesis 1:28; humans are called to what one of our ISCAST founders called “responsible dominion.”

Let me introduce you to one of Australia’s most eminent living scientists, who will make my point for me.

Graeme Clark won the Prime Minister’s Science Prize for his groundbreaking development of the bionic ear. At four years old his kindergarten teacher asked what he wanted to do when he grew up. Graeme’s father was almost deaf, and Graeme’s response was definite: “I want to fix ears.”

Listen to Graeme as he describes the role of a Christian co-creator serving the creator God.

So, a second reason for Christians to engage with technoscience is because we have the responsibility of being co-creators, working with the Creator for his purposes. And it is in technological ingenuity, more than any other field of human endeavour, where the Creator’s gift of creativity to humanity has the potential for amazing good and also for appalling evil.

3. Because we are called to be light and salt

A third reason Christians should engage with technoscience is because we are called to be a light in the darkness, offering hope, calling people to God, and contributing to understandings of the common good. Given that we are immersed in a technoscience world, will we engage or retreat?

Unless Christians think that retreat from the world is a valid option, we must engage with the cultural space in which we find ourselves. In a culture dominated by science and technology, Christians must be part of the conversation about creating human futures, about the common good, about where the global community is heading.

Technoscience is not one aspect of culture that we may or may not take an interest in, like sport perhaps, or music, whatever your preference is. The technoscientific world and mindset is the air that we breathe; or, to change the metaphor, it is the water that we swim in. We are totally dependent upon the outputs of technoscience. Perhaps you are a first adopter. Or perhaps you are a resister of technology for ethical or economic reasons. Either way, we are technologically enmeshed. And that enmeshment goes way beyond mere dependency.

It’s not just that we are dependent on technology to do things for us; our enmeshment in technoscience means that technology does things to us. It moulds us and forces us to think in certain ways, to behave in certain ways, to relate in certain ways. Christian and other thinkers have warned and written for decades about how technology moulds us: Jacques Ellul, Neil Postman, Marshall McLuhan. More recently Shoshana Zuboff in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism or Jonathan Haidt in The Anxious Generation, Andy Crouch in The Life We Are Looking For, or Shannon Vallor in The AI Mirror: Reclaiming Our Humanity in an Age of Machine Thinking. In New Zealand, Stephen Garner has, for decades, been at the forefront of what is called digital theology. Incidentally Stephen will be in Sydney for the ISCAST AI and human futures conference at the end of November; let me encourage you to join us.

4. Because science is a gateway drug

A final reason why we as Christians should engage with the creation as science reveals it to us is because science is a gateway drug.

As people leave the church and lose touch with traditional forms of transcendence, where do they go to be amazed, and indeed to worship? They turn to the creation. How ironic that the world’s most famous atheist started his talk at the Melbourne Global Atheist Convention with these words: “It is an amazing universe and you ought to be grateful.” Of course, Professor Richard Dawkins was forced to clarify: “However,” he said, “there is no one to be grateful to.”

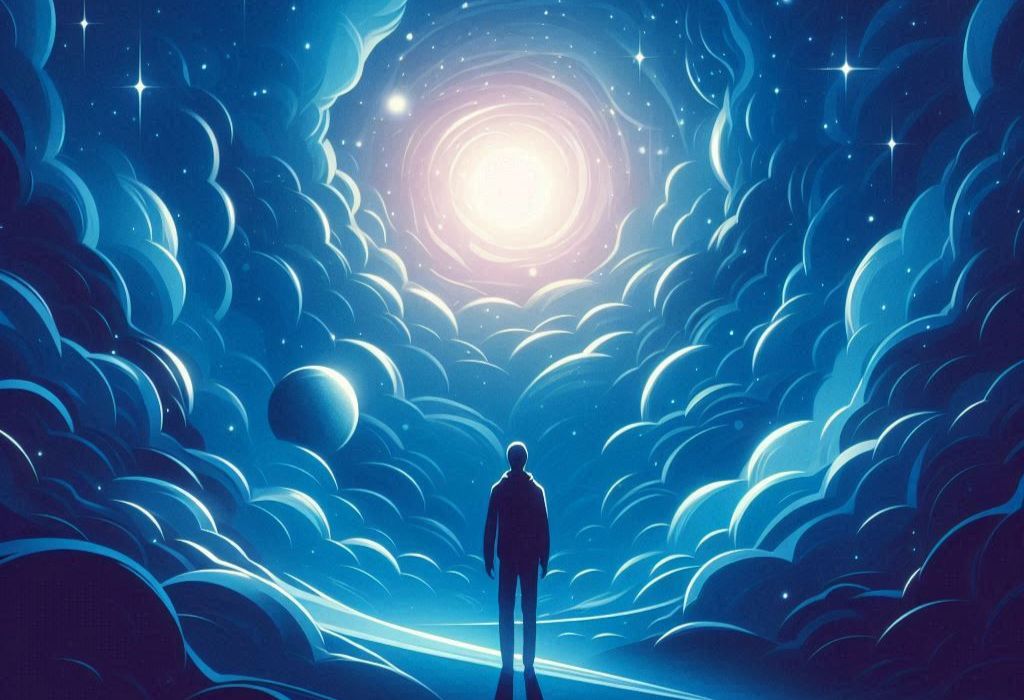

I mentioned Jennifer Wiseman who runs the Hubble Space Telescope. Here is one of her snaps revealing the wonders of God’s creation.

It is commonly known as the Horsehead Nebula. This is a star-forming region of our Milky Way galaxy where cosmic dust is being pulled together by gravity to form baby stars.

How many millions of people have looked at photos like this from the Hubble and been led to ponder the magnificent splendour of the universe. If only they knew Psalm 19, “The heavens declare the glory of God and the skies proclaim his handiwork.”

The ability of science to unveil the creation is a gateway drug to the creator. If only Christians could harness this power of the creation as it engenders awe and wonder, and then lead people to the one who is Creator and Lord of all.

This is a missional imperative. And in a culture where the drug of choice for many people is the wonders of science, where are the people of God?

What better way to introduce people to the creator than to take Queensland astrophysicist, Sarah Sweet, into St Margaret’s School? Sarah introduced the girls to the wonders of the universe and then went on to talk about her personal faith in the Creator of that universe.

As we think about creation and as we think about integrating our knowledge of origins, those are my four reasons why science and technology must be front and centre for Christians in our culture.

But wait. I can read your minds! What about the elephant in the room?

When it comes to creation and origins, there is often an elephant in the room. “What about the conflict between science and faith? What about Genesis 1 and 2, Adam and Eve, the age of the earth, death before the fall, evolution, the dinosaurs? What about Romans 5, 1 Corinthians 15, 1 Timothy chapter 2?”

Let me finish by offering five brief pieces of advice on elephant taming.

Five thoughts about elephant taming

1. Relax … Jesus is Lord!

My first piece of advice is to relax.

However we think about mainstream science and the biological history and age of the earth, Jesus is Lord. Jesus Christ crucified is the central affirmation of our faith.

Some Christians are convinced that so-called young-earth creation is the only faithful option. Others are convinced that mainstream science reveals truth and that robust Christian faith can get along with a scientific understanding the universe.

However, all Christians affirm that Jesus is Lord. And that is the message that we must stand for.

So, perhaps we need to relax a little about our differences on secondary matters and, united, affirm, and proclaim the name of Jesus.

2. Remember Aristotle’s causes

Secondly, let’s not forget Aristotle’s causes.

Long before Jesus, the Greek philosopher Aristotle spoke of four causes. We won’t go into them all now but let me remind you of a familiar illustration.

Why is the water boiling, asks the physics teacher. A bright girl puts up her hand. “It’s boiling because the energy of the gas is being converted to heat energy and then transferred to the molecules of water. They start to jiggle and eventually some vaporise and the water boils.”

At which, the teacher pulls out a tea bag and says …

“Actually, it’s boiling because I want a cup of tea.”

Which is the correct answer? Both, of course. One is the scientific answer; the other is an answer in terms of human decisions and intentions.

One is an answer in terms of mechanisms and particles. The other is an answer in terms of meanings and purposes. And they can both be right at the same time. There is no conflict between the scientific answer and the answer in terms of purposes and intentions.

For the most part, Christian theology and Scripture is not about particles or mechanisms. As Augustine said some 1600 years ago, we ought to leave that to science.

3. Remember the limits of science

As for science, it simply can’t answer questions about meanings and purposes. And, with all due respect to scientists, sometimes they are not very clear about the limits of science. Sometimes scientists and those who love science tend to overstate the reach of science.

My advice to them and perhaps to some of us is to remember the limits of science. In short, science can’t answer moral questions. “Is torture wrong?” is not a scientific question, even if science can “improve” techniques for extracting information from people.

Nor can science answer philosophical questions. For example, surprising as it may be, science can’t prove to us that science leads to truth.

And nor can science answer those questions that we all face once in a while that stop us in our tracks. The existential questions … What is the purpose of life? Is there a God? Or, more personally, why did our oldest son die of cancer? Or the question of our nine-year-old, youngest son: “Mum, you aren’t going to die are you?” “No, why?” “Well, Ben died, so anyone can die.”

Science is great at uncovering the natural world—the creation. But it is totally incompetent to deal with the most important questions of human existence.

4. Watch your French

Now for a French lesson.

I think one of the most common confusions about reading Scripture is that we forget that while it is the word of God, it is also the word of human beings. It is literature. And in order to interpret any type of literature we have to know our French. Well, we only have to know one French word, and that is “genre.”

genre

/ˈʒɒ̃rə,ˈʒɒnrə/

noun

1. a style or category of art, music, or literature.

If you pick up Harry Potter and the Philosophers’ Stone expecting to learn a sure-fire way of turning metal into gold or of making an immortality potion, then you would be mistaken. You are mistaken because you didn’t realise the genre of literature you were reading. Harry Potter is fantasy, not science. And when it comes to the Bible, we have numerous types of literature; numerous genres. So, that’s my fourth piece of elephant taming advice; watch your French.

When you read Revelation or Ezekiel, when you read a Gospel or Genesis chapter 1, or a letter of Paul, ask yourself, what sort of literature am I reading? What is the author’s intention here? I won’t answer it now, but perhaps one of the questions that focuses our minds when it comes to origins is this: “Did the author of Genesis chapter 1 intend to teach us how many hours it took God to make the universe?” That’s another way of asking, what sort of genre is Genesis chapter 1?

5. There are no simple answers

Finally, if we are going to tame the elephant, I think we ought to be honest with ourselves, and recognise that when it comes to the relationship between scientific understandings of origins and theological understandings, there will never be an easy, problem-free position. Like the Facebook relationship status, it’s complicated!

For the person convinced of a literal six-day creation and a young earth, complications arise when explaining how mainstream science can get some things so wrong, as well as explaining where the line lies between figurative and more literal interpretations of Scripture.

For the person who thinks that mainstream science probably has the big picture correct, complications arise around how we think about Adam and Eve and the nature and effects of the fall.

Let’s not pretend that if only people could see it our way, all the complexities would be removed.

Let me finish now with a Bible reading. It’s one of the many creation accounts found in the Scriptures and it’s a glorious drawing together of origins with the ultimate fulfilment of the plan of the Creator.

Colossians 1:15–20

15 The Son is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation. 16 For in him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities; all things have been created through him and for him. 17 He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.18 And he is the head of the body, the church; he is the beginning and the firstborn from among the dead, so that in everything he might have the supremacy. 19 For God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in him, 20 and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross.

May our time together thinking about creation lead us to worship the one through whom and for whom all things were made; the one who made our peace with God through his blood shed on Calvary. Amen.