Download PDF

A reflection on scientific and religious moments of insight.

The Eureka Moment

James Garth

James Garth [BEng (Aero) (Hons), MAIAA, AMRAeS] is a practising aerospace engineer and a member of ISCAST.

Many scientists will be familiar with the concept of the ‘Eureka Moment’, that special point in time when you realize that you have discovered something special, an insight that adds to the sum of human knowledge, something unique that is verifiable and absolutely true. Engineers feel it too, in the sudden realisation that one’s design is elegant and effective, and inherently works.

These deeply satisfying moments remain the holy grail of scientific endeavours. And yet, despite our best efforts, these moments remain stubbornly elusive, rare and unpredictable. The distinguished scientist Fred Hoyle once compared notes with Richard Feynman, and quizzed him about his own ‘Eureka Moment’ experiences.

‘The elation lasts about 10 seconds in the short term and about three days in the long term’, said Feynman. ‘I’ve had three of them.’ (Pause.) ‘Not much to show really, nine days’ pleasure for a lifetime’s work…’

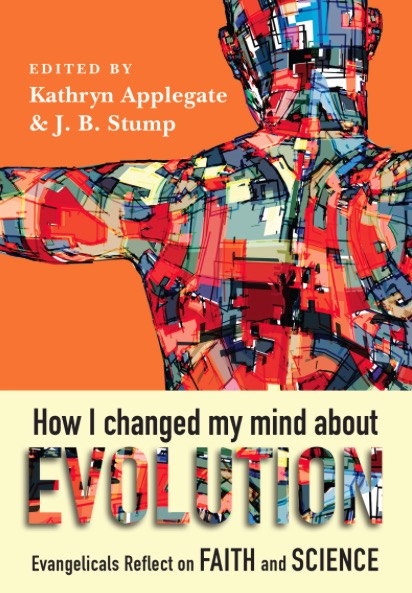

Given the scarcity of such experiences, as scientists we may, like Feynman, sometimes wonder whether the whole enterprise is worth it. In many ways this is not unlike the dilemma faced by the religious believer, the person who eagerly seeks God but at the same time finds His transcendent presence intermittent, perhaps even elusive. I suggest that we can gain a couple of points of insight by comparing scientific ‘Eureka Moments’ with religious ones, as I think they have more in common than we might initially suspect.

The first insight is critical: we can no more instigate or precipitate a religious ‘Eureka Moment’ than we can a scientific one. Even scientists must rely to a great degree on both faith and hope when they set up research projects, having to live and work in the hope that their research grants will yield some moments of insight, all the while doing so in the knowledge that such outcomes can never be certain.

The second point is just as critical: although we cannot instigate such moments, what we can do is at least allow ourselves to be open to the possibility of them. Further, it seems to me that this very attitude of openness, this striving for a moment of understanding, is in fact a necessary pre-requisite for the possibility of such moments actually occurring…

A personal anecdote

It was December 19, 2008, about 7a.m. I was standing alone, in the concourse at Flinders Street Station, just behind a short queue of commuters who were patiently waiting to purchase a morning croissant or coffee from a convenience stall. I felt at ease, in a casual frame of mind, just about ready to embark upon the next leg of my commute to work.

And then, out of the blue I heard a solo bugle begin to play, strong, pure and crisp in the morning air. I recognized it instantly as a Christmas Carol

– appropriate, of course for this time of year. ‘Hark the Herald Angels Sing’ or some such hymn – I had never really cared for hymns, nor consciously known any of their lyrics…

Then, suddenly, something happened. My entire body and mind surged with something that felt like electricity, running, pulsating from head to toe. My feet felt rooted to the floor as I physically bristled with what I can only describe as an intense and electric sensation.

As the melody played, I felt each and every word of the hymn – words I was unaware that I knew – imprint itself with precision and impact into the very centre of my mind. Each word hung there, practically audible, striking like the palpable blows of a hammer as for once I listened – actually listened…

Hark the herald angels sing ‘Glory to the newborn King! Peace on earth and mercy mild God and sinners reconciled.

Joyful, all ye nations rise, Join the triumph of the skies.

With the angelic host proclaim: ‘Christ is born in Bethlehem’.

Hark! The herald angels sing ‘Glory to the newborn King!’.

Every invisible syllable seemed to impact, every line seemed alive, pertinent, reverent and beautiful, drenched with high Christology, as if calling to my attention anew this definitive revelation of God to humanity. The music continued, again every word carving itself into the forefront of my consciousness:

Hail the heav’n-born Prince of Peace! Hail the Sun of Righteousness!

Light and life to all He brings, Ris’n with healing in His wings. Mild He lays His glory by,

Born that man no more may die, Born to raise the sons of earth, Born to give them second birth. Hark! The herald angels sing ‘Glory to the newborn King!’.

What was happening here? A beautiful, unexpected moment of transcendence? Here, of all places, in the bustling hub of inner-city Melbourne? Was it – dare I say – a Eureka Moment? Perhaps one of an entirely different sort, yet every bit as ‘real’ as those obtained by scientific insight? How are we to explain such glimpses of transcendence? The physicist John Polkinghorne has suggested that God interacts with us through an energy-less information transfer, inputting information into our brains in acts of special providence. I believe he is absolutely right. I could mention other such moments in my life, a handful more in number than Feynman’s experiences, though not by much. Unlike Feynman though, I feel that’s not too bad for a life’s work, at least at this point!

As scientists we hope patiently and expectantly for the prize of Eureka moments. But, as religious believers, do we also exhibit such hope and expectancy? Perhaps the shadow side of science itself is that it has conditioned us to treat moments of transcendent, religious insight with some sort of fear, frightened that they be in fact somehow contrary to reason. Blaise Pascal once said that the cure for fear of religion was:

first to show that religion is not contrary to reason, but worthy of reverence and respect. Next make it attractive, make good men wish it were true, and then show that it is.

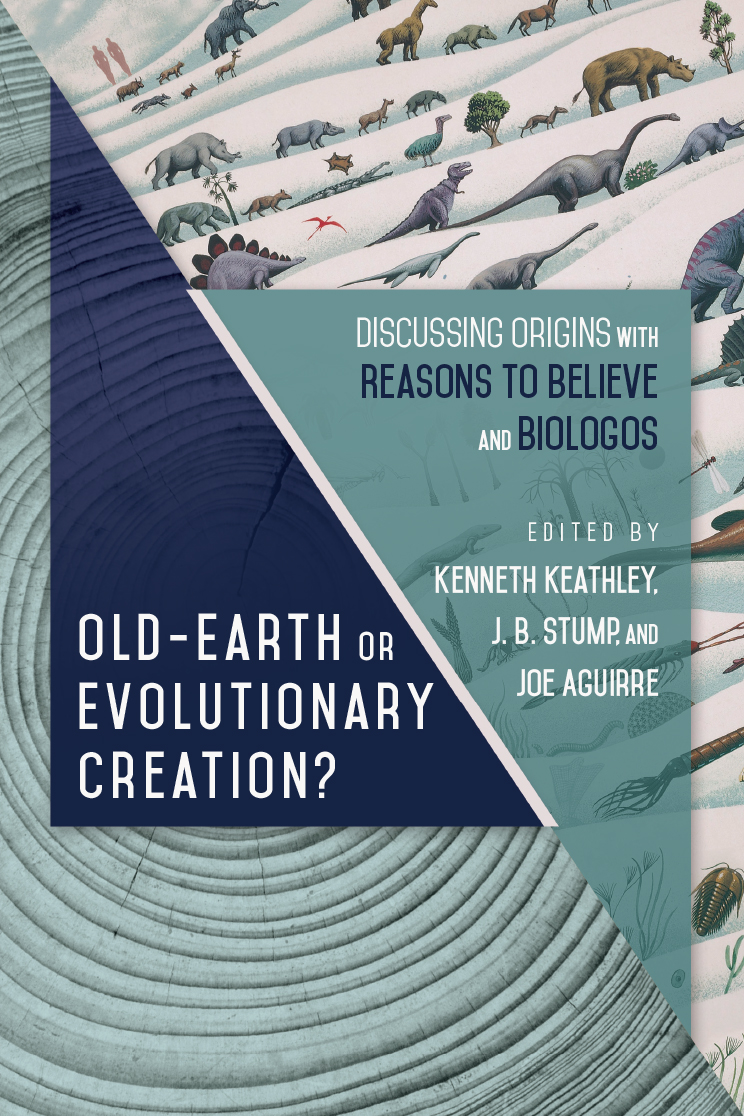

The working life of the scientist is guided by the ideal of a universe that is inherently rational and intelligible, with the ultimate goal being that a genuine, deep understanding of the structure of the physical world is something both possible and expected.

The moral life of the Christian is guided by the ideal of the existence of a completely loving, all-powerful being, with the ultimate goal being the notion that there is more beyond this life, that death will be defeated, that justice and moral endeavour will not be in vain.

Perhaps, and it is my ongoing hope and prayer, as Christian scientists we can stimulate and encourage a full measure of openness not just to the former sort of life, but the latter as well.