How to read the Bible in the 21st century

Frank O’Dea, December 2010.

Download PDF

How to read the Bible in the 21st century

Frank O’Dea

Frank O’Dea was a parish priest in Perth. His principal ministry now is working with a team of lay people putting on Life in the Eucharist programs. He assists in neighbouring parishes on Sundays and ministers at St Francis chapel in the Eastland shopping centre (Ringwood, Victoria) on weekdays.

This paper was presented at the ISCAST Intensive, ‘Who says? The use and misuse of the Bible in an age of science and technology’, held in Melbourne in October 2010.

Abstract

This paper give some history of how the Bible has been understood over the centuries. The rise of science and the Enlightenment made some people think that the only truth is what science and reason can prove. This has led to much abuse of the Bible. We need to recover the truth that is also found in parable, poetry and metaphor. We must understand the literary form used by each author. We need prayer to get a deeper understanding of the Scriptures.

I would think that all of us doing this intensive would agree with this quote from the last council of the church in the 1960s which put out a wonderful document on scripture called ‘Dei Verbum, the Word of God’.

The church has always venerated the divine scriptures just as she venerates the body of the Lord, since from the table of both the word of God and of the body of Christ she unceasingly receives and offers to the faithful the bread of life especially in the sacred liturgy.

Dei verbum, 21

I find Karen Armstrong’s ideas are a good framework for this discussion. She says there are two ways of thinking, speaking, teaching, acquiring knowledge: mythos, logos. (Karen Armstrong, On the Bible, Allen & Unwin).

Mythos deals with story, art, song, dance.

Logos is rational, calculating.

Let’s look a little more closely at these two items.

Mythos is primary, story; it is concerned with what is timeless and constant in our existence. It looks to the origins of life, foundations of culture, deepest levels of the human mind. It is not concerned with practical matters but with meaning. It is rooted in the unconscious mind, and can’t be demonstrated by rational proof. Its insights are more intuitive, similar to those of art, music, poetry, sculpture and are embodied in cult, rituals, ceremonies. It evokes a sense of the sacred, enables comprehension of deeper currents of existence. It is not much interested in whether an event actually happened, but more concerned with the deeper meaning of the event.

All cultures had their mythos, e.g. aborigines have their dreaming stories, centred on the Rainbow Serpent. Greek, Roman, Nordic, African cultures all had creation myths which helped people to have some understanding of how things are as they are.

Logos is equally important.

It is the rational, pragmatic, scientific thought which enables us to function well in the world. It relates exactly to facts, corresponds to external realities, works efficiently in the mundane world. Logos looks ahead, tries to find something new, achieves greater control of environment, invents things.

For most of human history, mythos and logos were in harmony.

People had some awareness of their place in the total scheme of things through mythos, and went about their daily practical lives using logos. The aborigines had their dreaming, the rainbow serpent, to explain how the mountains, the lakes, the rivers were formed. When they went hunting, they would use logos, for example, keeping down wind of their prey and finding ways to ambush them.

The Christians had their creation stories in the Bible, the conquest of the promised land, the parables of Jesus. These answered the big questions of life: why are we here, what’s the purpose of life, is there life after death etc? Then in their workaday lives they would use logos to build their towns, do their trading and farm the land.

Christians were taught that reading the Bible is a spiritual exercise; it needs discipline of mind and heart, and it is best done in a liturgical setting.

For centuries, lectio divina, divine reading, was the method used for understanding scripture. One would take a scripture text, read it several times and ponder over it in prayer, asking the Holy Spirit for guidance in finding out what this passage means for the reader at this time, how this passage could help in the spiritual journey. Prayer is an essential element in reading the Bible. The Jewish philosopher, Martin Buber said, ‘Stand before the Bible as Moses stood before the burning bush and listen intently’. Ambrose said, ‘We speak to him when we pray; we hear him when we read the divine sayings’.

If I were asked to describe in one sentence what the Bible was about – a risky question – I would say it describes the relationship between God and his people and among people.

As soon as we begin talking about God we are talking about mystery, as in the end God is incomprehensible. The best way to talk about God is through poetry, metaphor, music and … silence. Therefore to understand the God of the Bible we may not be able to accept the surface meaning of the words but must dig deep like mining for gold – and this can be hard work.

Some events like the Israelites putting to death all the inhabitants of the city of Jericho are not acceptable, as this doesn’t harmonise with the fullness of revelation from Jesus that God is love and loves all his people. We may find in prayer that God is asking us to put to death the evil tendencies within us – selfishness, avarice, anger …

Justin, Origen, Antony of Egypt, Athanasius, Jerome and many others all insisted on the role of prayer in the exercise of reading scripture.

Augustine insisted that reading scripture must lead to love of God and love of neighbour. For all these people reading the Bible had to be done in harmony with a life of discipline. You don’t just read scripture, you do it. Incidentally, the ancient Greeks such as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle also said that you can’t discover truth unless you lead a disciplined life.

This harmony of mythos and logos became disrupted in what we can call the modern era in which science developed, although the earliest scientists had no problem.

Copernicus who discovered the earth revolved around the sun, and which the pope of the time approved, said ‘My science is more divine than human’. Galileo who built on the ideas of Copernicus, Kepler and Brahe believed that his research was inspired by divine grace. Other scientists discovered microbes, learned ways to control the environment and increased farm productivity. All these discoveries were a feature of the pragmatic, scientific spirit of logos, which began to take control and overshadow the importance of mythos.

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) insisted that all truth, even the most sacred doctrines of religion, must be subjected to the stringent critical methods of empirical science.

Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) synthesized the findings of his predecessors by a rigorous use of the evolving scientific methods of experimentation and deduction. Newton believed in God as the great ‘Mechanick’, running a precise, mathematically controlled universe. He became totally immersed in the world of logos and couldn’t appreciate there were other forms of knowledge such as intuition. He wrote: ‘Tis the temper of the hot and superstitious part of mankind in matters of religion ever to be fond of mysteries and for that reason to like best what they understand least’. Newton became obsessed with the desire to purge Christianity of its mythical doctrines such as the Trinity and the Incarnation. Modern science was beginning to discredit mythos.

The philosophers, Rene Descartes (1596-1650), Thomas Hobbes (1588- 1679), John Locke (1632-1704), Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) all followed this general trend. This era came to be called the Enlightenment, the Age of Reason.

Printing was invented – a huge step forward for humankind. For the first time in the Christian era, the Bible became available to anyone who could read. Now people could physically see the Bible as a single volume rather than a collection of many books that were written by hand. Scripture was now read for the information it could impart. The words of scripture, once seen as earthly replicas of the divine Logos, lost their numinous dimension.

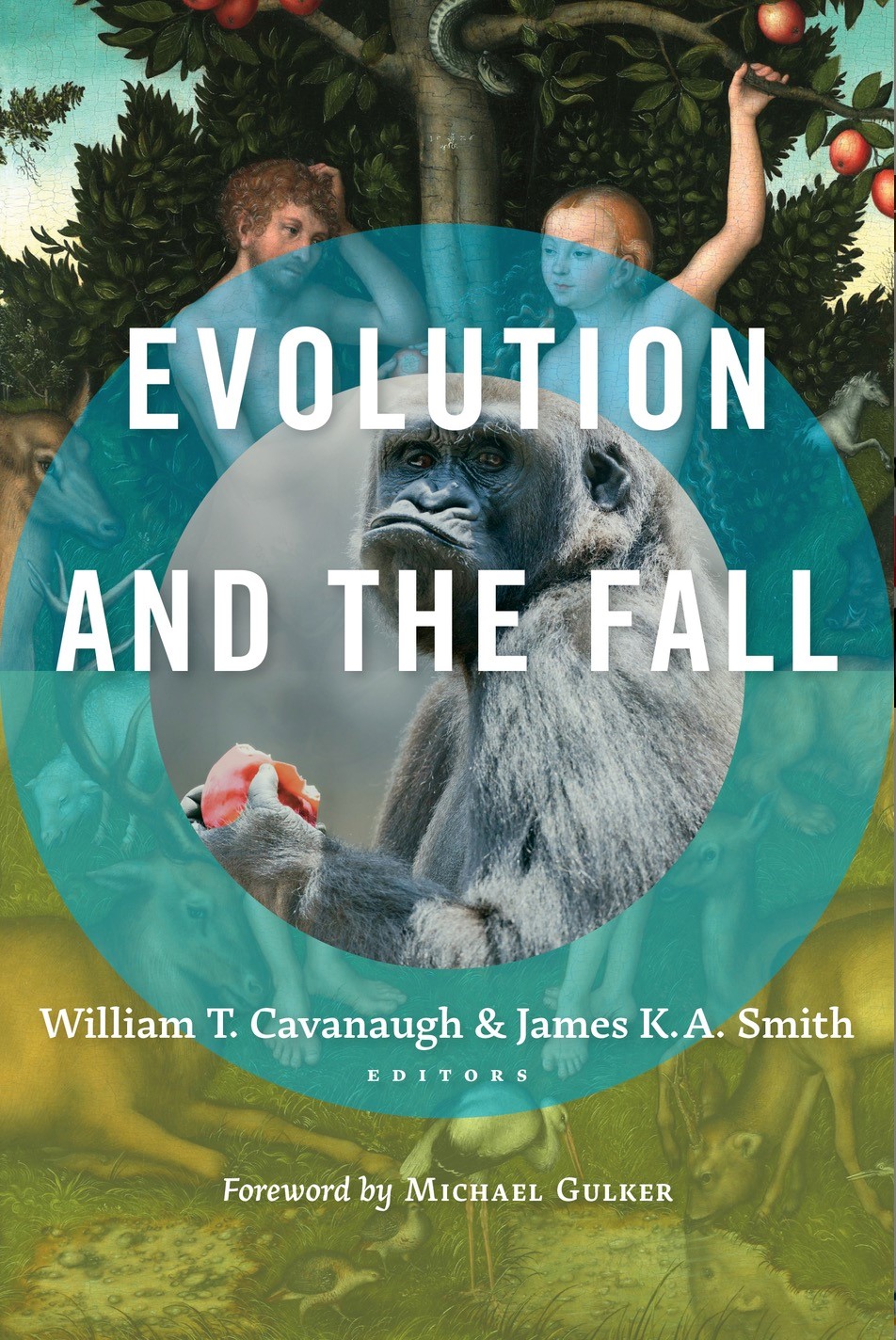

In 1859 Charles Darwin (1809-82) published On the Origin of Species and later, The Descent of Man suggesting Homo sapiens evolved from the same proto-type as gorilla and chimpanzee. Darwin didn’t attack religion, and at first the response to his theory was muted. However, Thomas Huxley and others used Darwin’s theory to further the conflict between science and religion.

Mrs Humphrey Ward in 1888 wrote in a novel, ‘If the gospels are not true as fact, as history, I cannot see that they are true at all, or of any value’. Arthur Pierson wrote a book called Many Infallible Truths. The very title showed that people were looking for certainty in an uncertain age. Pierson wanted a ‘Baconian system’, that is, one based on the empirical methods of science as championed by Francis Bacon. Archibald Hodge wrote ‘The scriptures are the Word of God and hence are absolutely errorless and binding on the faith and obedience of men’.

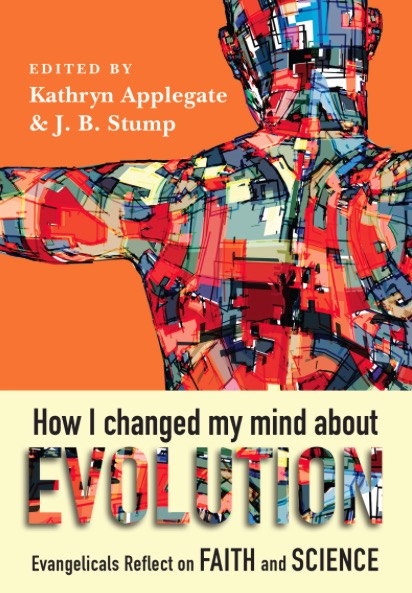

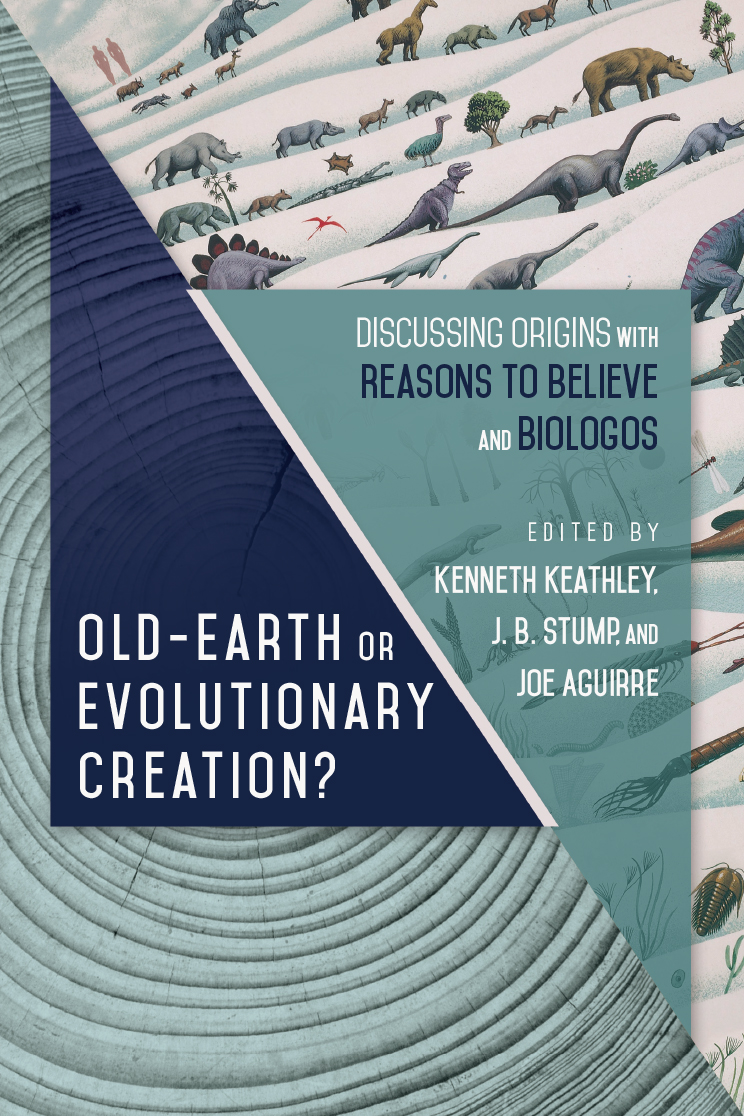

This is the position that many people adopt today and has led to so much misuse of the Bible through conflict with science and history and extremism such as Creationism, Intelligent Design, Young Earth theories and Reconstructionism.

What has also happened is that the word ‘myth’ has now come to mean a lie, an untruth. This is a tragedy for the English language. What was once a very rich word with deep meanings has become totally distorted. We have almost completely lost the ancient tradition of seeing mythos in the Bible.

Even before the age of science as we know it, Augustine had this to say, ‘… the interpreter must respect the integrity of science or he would bring scripture into disrepute’. Scripture and science are in harmony when both are rightly understood. Centuries later, Vatican II echoes this thought of Augustine, ‘Those who search out the intention of the sacred writers must

…. have regard for ‘literary forms’ … history, prophecy, poetry or some other type of speech’. (Dei Verbum, 12)

One of the literary forms that humanity has used for millennia is mythology. We could call them camp fire stories, passed on from generation to generation, by word of mouth, and only later put into written form. These may not be true from a scientific point of view, that is, using logos, but they contain very valuable truths nevertheless.

Let’s take the second creation story as an example, and ask what can we learn from the story of Adam and Eve and the garden of Eden.

First, the name Adam simply means ‘the man’. It’s interesting that the NRSV translation doesn’t use the word ‘Adam’ at all; it simply says ‘the man’, that is, everyman. The woman, Eve, is as closely linked to the man as possible, ‘bone of my bone, flesh of my flesh’. The NRSV only uses the name ‘Eve’ at the end of the story when it says the man named his wife ‘Eve’. Men and women are equal. The garden has everything that humans need – God is a good provider.

We can be avaricious and disobedient; we want to possess every good thing that we see. We don’t keep to the boundaries that God has set; we want to be like God. We sweat to make a living and birthing is very painful for women. Here we find the author is suggesting a reason for things being as difficult as they are – aetiology. We don’t live in paradise, and we have to accept this fact which can be so frustrating at times.

In the DVD Test of Faith, the astrophysicist Katherine Blundell says that Genesis was written by a non-scientist for non-scientists.

My own observation would be that the Bible is more mythos than logos. After all, story telling is the primary way to teach. We all love stories. We tell our children ‘fairy stories’ not because there was such a person as Little Red Riding Hood or Goldilocks or the Seven Dwarfs, but to teach children there are good people and wicked people and life is very much a conflict between good and evil.

Vatican II says, ‘The interpreter must investigate what meaning the sacred writer intended to express … as he used contemporary literary forms in accordance with the situation of his own time and culture’. I see this as a warning not to expect the Bible to be scientifically and historically accurate. Always, we must look for the spiritual message, and not get caught up in the useless task of questioning the scientific and historical accuracy of scripture.

Turning to the New Testament, the Council of Vatican II says, ‘God wisely arranged that the New Testament be hidden in the Old and the Old be made manifest in the New.’ (Dei Verbum, 16)

We must be aware that the gospels are not biographies of Jesus as we understand the word in modern times. There’s nothing in the gospels about Jesus’ appearance, whether he was short or tall, fat or thin, nothing about his mannerisms or the kind of voice he had, and nothing about his early life.

In his book An Intro to Reading the Bible, William Parker says ‘The gospel is good news proclaimed to an audience inviting a response’. ‘Inviting a response’ is a very important element in the gospel. A gospel is not the life story of Jesus; rather it is passing on to us the good news that he proclaimed and challenging us to accept his teachings in full and to live according to those teachings.

There are four separate and distinct gospels and it’s helpful to notice the uniqueness of each of them. Each evangelist arranged the details of his gospel depending on the circumstances of his community.

Let’s take a simple example. Matthew gives us what we call ‘The sermon on the mount’. Matthew’s community had a good percentage of Jews as well as some Gentiles. Throughout this gospel we see that Matthew is keen to show Jesus as the new Moses, so Matthew has Jesus giving his teaching on a mountain just as Moses received the Ten Commandments on a mountain. These 3 chapters are probably a summary of Jesus’ teachings – it seems highly unlikely that Jesus would give such a long teaching in one burst. This ‘sermon’ includes what we call the Beatitudes. Jesus says that he has come not to abolish the law or the prophets but to fulfil them, and he makes the point very strongly that he expects a higher standard of conduct than was current at the time. This teaching also includes the Lord’s Prayer.

In contrast to Matthew, Luke says Jesus came down from the mountain to a piece of level ground. Luke’s ‘sermon’ is much shorter than Matthew’s, all contained in less than one chapter. Luke adds woes to the blessings, severe warnings to the rich, those who are well off and those held in high esteem. Luke locates the Lord’s Prayer elsewhere and it is a shorter version than Matthew’s. The discrepancies needn’t bother us – the gospels are not biographies.

We must keep in mind that just as Jesus taught theology by means of stories which we call parables, so the evangelists taught by means of stories. Sometimes these are quite lengthy and elaborate stories. This is mythos in action. However when this is applied to the New Testament, people may feel threatened especially when we turn to the infancy stories of Matthew and Luke. We grew up on these stories from childhood and generally accepted them as historically true. But let’s look at them now as adults and be open to the difficulties that come from our childhood experiences.

When we look at Matthew’s infancy narrative we find these elements:

Joseph has centre stage, he is the principal adult in the story.

An angel appears to Joseph to tell him that Mary is expecting a child but he need not be afraid to take her as his wife because the child is the work of the Holy Spirit.

Throughout the story, Matthew says the Old Testament is being fulfilled.

Matthew tells of the wise men coming from the east, following a star, being directed by Herod to Bethlehem, offering their gifts to Jesus and being told to go home by another route.

Herod is afraid, feeling threatened by a rival to the throne.

Joseph is told by the angel to go to Egypt to escape Herod.

Herod slaughters all the male children in Bethlehem.

Joseph is told by the angel to return to Nazareth after the death of Herod.

When we look carefully at this story we find many elements are based on the Old Testament. Matthew was always very keen on linking Jesus to the Old Testament to show his Jewish members there was a continuity between the Old Testament and Jesus.

Gen 37:5 The Joseph of the Old Testament was an interpreter of dreams; in fact, it was his involvement with dreams that led his brothers to sell him off to traders going to Egypt where he interpreted the dreams of Pharaoh.

Is 7:14 says ‘the virgin shall conceive’.

Number 24:17 says ‘a star shall come out of Jacob’.

Micah 5:2 gives Bethlehem as the birth place of the Messiah.

Is 60:6 talks of gifts of gold and frankincense.

Hosea 11:1 says ‘out of Egypt I called my son’.

Jeremiah 31:15 says, ‘A voice is heard in Ramah, lamentation and bitter weeping.’

Finally, Matthew always sees Jesus as a Moses figure.

Matthew’s story prefigures Jesus’ life in these ways:

He is misunderstood by his own people especially the rulers.

He is persecuted.

During his ministry there was the threat of death.

He welcomed the Gentiles.

God’s will is fulfilled.

Luke’s story has nothing in common with Matthew’s. In Luke:

An angel appears to Mary, Mary conceives.

Mary and Joseph must go to Bethlehem for a census.

There is no room at the inn.

Mary gives birth and Jesus is laid in a manger.

An angel appears to shepherds and tells them the good news.

The shepherds are given a sign.

Mary treasures the words in her heart.

As in Matthew, Luke’s story contains many elements that prefigure the life of Jesus.

He is inconveniently subject to civil authorities.

He is named as the Son of David.

The lowest class, the shepherds, are the first to see him.

There is interaction between heaven and earth.

An angel tells the good news.

The manger is a sign that Jesus is the bread of life.

Glory and praise is offered to God.

His birth mirrors his death – ‘wrapped him in cloth strips, placed him in a manger, because there was no place’ anticipates ‘wrapped him in a linen cloth, placed him in a rock-hewn tomb where no one had yet been laid.’ (Luke Timothy Johnson, The Gospel of Luke, The Liturgical Press, Minnesota, 1991, p. 52)

‘We are dealing … not with a scientifically determined chronology, but with purposeful storytelling.’ (Johnson, p. 53)

In the 21st century we need to read the Bible as a book of prayer and be sensitive to its different literary forms.