Religious Origins of Modern Science

The ISCAST Vic Allan Day Memorial Lecture 2017 held at Ridley College.

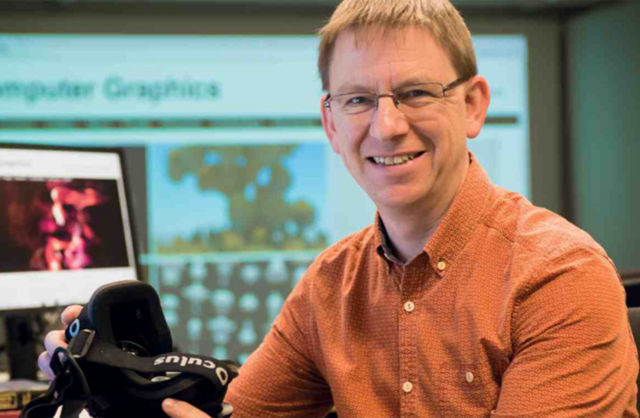

Prof. Peter Harrison FAHA

It is sometimes thought that modern science developed largely independently of, or even in opposition to, religion. Historians of science, however, have proposed various ways in which religion might have played a significant role in the emergence of modern science. This lecture will evaluate some of the standard arguments for the religious origins of science, and put forward some new ideas about the influence of religion on the development and persistence of science.

Peter Harrison is an Australian Laureate Fellow and Director of the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Queensland. Before moving to UQ he was the Idreos Professor of Science and Religion and Director of the Ian Ramsey Centre at the University of Oxford. He has published extensively in the field of intellectual history with a focus on the philosophical, scientific and religious thought of the early modern period, and has a particular interest in historical and contemporary relations between science and religion. He is a founding member of the International Society for Science and Religion and a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. In 2011 he delivered the Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh. Author of over 100 articles and book chapters, his six books include, most recently, The Territories of Science and Religion (Chicago, 2015), winner of the 2016 Aldersgate Prize.

Peter will be speaking at the ISCAST Conference on Science and Christianity in March 2018.

Lecture: Download mp3 [34.4 MB]

INTRODUCTION

CHRIS MULHERIN: Let me introduce Peter briefly; Peter is an eminent Australian scholar who, we are fortunate, has come back to Australia to the University of Queensland after his time in various places overseas, including Oxford. In Oxford he was the director of the Ian Ramsey Centre for Religion and Science, and he was also the Andreas Idreos Professor of Religion and Science, a position that’s now being filled by Alister McGrath. He’s an eminent scholar, he gave the Gifford lectures in 2011, his latest book, ‘The Territories of Science and Religion’ is based on his Gifford lectures and we are extremely fortunate to have him here tonight. He’s a fellow of ISCAST and a fellow of other learned societies as well, better known ones than ISCAST I can tell you. And this afternoon he gave a public lecture at Melbourne University which was booked out although some of the people saw the rain and didn’t come I think and some of those people actually decided to come here tonight. So, welcome to those people who didn’t know you were coming to a meeting here tonight but you’re now here. Tomorrow Peter will be speaking at a staff and post-graduate seminar for the University of Divinity at lunchtime and then he flies back to Queensland. Without more ado, will you please welcome Peter Harrison.

[Applause]

1:37

LECTURE

PETER HARRISON: Well thanks Chris for that welcome, it’s a real pleasure to be here and to be doing the Alan Day Memorial Lecture. I met Alan only on one occasion but he impressed me as a very lovely gentlemen and obviously his mark is still obvious in this group, ISCAST. Now, let me just make sure … Got to get the slides going … So, I noticed that the UQ logo wasn’t there, I’ve got to have the corporate badge in there for the University of Queensland note. But tonight, I’m going to talk about the religious origins of modern science and I’m going to speak about these five different things. I want to start simply with the general question of what is it when we attempt as historians to explain the origins of something like science, and then I’m going to talk about the different ways that religion has impacted on science and the remaining three points are just specific examples of the ways in which religion might influence the development of science which I’ll go into in some detail.

So, we’re going to start with this first question; what is it when we say we’re going to explain modern science? And for historians, we should be clear that modern science begins in the 17th century, it takes on its distinctive form then, so the period I’m talking about here first of all is in the 17th century, which happens to be the century that I know most about as an early modern historian. It’s easiest, I think, to get a sense of what this question entails, to set out first of all some ways in which we should not attempt to explain the origins of modern science. I’m going to do that first and then I’m going to move onto the positive object. Here’s an example of how not to explain the origins of modern science because what we have here, you can see that it was taken from a website called ‘No Beliefs.com’, so the clue is in the title. The idea here is that science got a start in antiquity and there’s certainly truth in that which I’ll come back to, but something stopped it and the something that stopped it was essentially Christianity and that the origins of modern science then is to be understood in terms of science liberating itself from the strictures of Christianity. So, the kind of explanation offered here is that there’s a somewhat natural progression, that societies will do science if left alone, but something can stop them – what is that thing? It’s religion. How do we then account for the origins and growth of science? It must be then to do with the extrication of science from the clutches of religion.

4:39

Now, my suggestion in this talk is that something like the opposite is the case, that it was only when we had a firm partnership between science and religion that we see for the first time in the 17th century that it becomes possible to consolidate and to develop something like modern science. And that in fact, the Middle Ages is characterised by separation of science and religion and that’s why things tend to be all over, there’s quite a lot going on, much more than we often here and modern science just doesn’t get up and running until the 17th century.

I’ll just give you one more example of how common this view is, so Carl Sagan’s famous cosmos which is now being rehearsed by Neil deGrass Tyson along much the same ideological lines, suggests that nothing happened in the Middle Ages and we’ve got to read this from the top down, that after the Greeks and the flourishing of Hellenistic science, we have a dark period and until we get Columbus, Copernicus, Kepler and so on, nothing’s going on. So, the truth to this is that modern science doesn’t take off until about here but the assumption that nothing was going on in the Middle Ages is certainly false and the assumption that Christianity is responsible for the inhibition of the natural growth of science is certainly mistaken.

For those of you who were at the last lecture, these understandings of science tend to be informed by a progressive notion that’s characterised by this guy [Auguste Comte]—you can see his dates there, essentially in the 19th century—argued for a progressive understanding of history, a history that passes through these three phases. And again, for me, this is a way about how you do not explain science – you don’t take some theoretical conception of historical progress and stamp it onto the facts. What historians like to do is to look at the historical contingencies, they don’t like the idea that there’s some kind of underlying structure to history that will unfold in a particular way. That’s kind of a Hegelean way of understanding history that I can assure you is not popular amongst historians of science. Nonetheless, it is interesting that the idea of a structured history and particularly three phases of history, actually has its origins in Christian understandings of how history is structured and I’ll just give you perhaps the most prominent example, Joachim of Fiore who has three stages of history based on a Trinitarian conception of how history will unfold. So, there are quite interesting connections between notions that history has a particular shape and then secularised versions of this shape of history that we see emerging in the 19th century but I won’t say too much more about that except I have a general interest, as do some people in my research group, about particular understandings of the patterns of history and how they inform a vast array of projects from New Atheist understandings of science to the big history project to even science fiction.

8:03

But this notion, interestingly, if we think about the theological origins of structured conceptions of history, we find that at the time of the Protestant Reformation, we also get rhetoric about what impeded the growth of knowledge and science, and the protestant reformers accused the Catholic Church of impeding science. So, the pattern of history, that nothing happens in the Middle Ages, that we see in secular understandings promoted by the No Belief.com and the Cosmos television series, to some extent owe their origins to Protestant insistence that we have a dark age when the Catholic Church ruled and only after the Protestant Reformation was it possible for science to come into existence. And you can see here Francis Bacon, who’s a key figure in getting modern science off the ground in the 17th century wants to argue that once we have the Protestant Reformation, it’s possible to have a reformation for all forms of learning. Now, I think there’s actually a truth in this, and I’m not suggesting that the Catholic Church impeded the growth of knowledge throughout the Middle Ages, but nonetheless, the Reformation was an occasion for a rethinking of knowledge. The Reformation is certainly implicated in the sorts of challenges to authority that made the scientific revolution possible, but I won’t talk about those in too much detail.

Let me just say that the arguments between who owned history between Catholic and Protestants are significant for what will then become the European Enlightenment’s understanding of the relations between science and religion and I’ll just give you a couple of further examples. And these are really saying the same things that Francis Bacon says, so the puritan Gilbert Burnet in his history of the Reformation, ‘we’re trying to restore Christianity to what it was and we have later and darker ages’. So, the notion of a dark age emerges here in Protestant polemic. Cotton Mather, the Puritan English-American thinker, ‘incredible darkness was over Europe, the revival of letters prepared the way for the Reformation and the advancement of the sciences’. So, it’s quite interesting that the model that I’m suggesting to you is not a terribly good one for explaining science. We find it in Protestant, anti-Catholic polemic and what happens subsequently is that rhetoric is secularised into an Enlightenment understanding that I’m going to jump to.

10:51

Now, I’m going to jump two slides here, these are Reformation themes … but here we get for the first time the Enlightenment understanding of how history works and my suggestion would be is that this is simply a secularisation of the Protestant Reformation critique of Catholicism, but now it’s extended not just to one form of religion but to the whole of religion. And so in this statement, now we see that it’s not Catholicism that’s impeding science but it’s the whole of religion that impedes science. And so, we have a secularisation of a Protestant polemic against Catholicism and now it’s broadened to cover the whole range. So, the triumph of Christianity signals the decadence of learning, the implication here is that it’s only when we can move away from the power of religion in society that it’s possible for science to flourish. And that’s a very common motif and interestingly, I think its origins lie in Protestant-Catholic polemic.

All that said, that is not the way that historians think about the emergence of modern science. How do they think about the emergence of modern science? And what I’ve said is that historians think about rather than there being some underpinning theory of history that we can apply and give us an explanation, they look to specific historical contingencies so that it’s hard to get what we might call a ‘systematic account’, but nonetheless, it’s to the contingencies that we look. But there is a way, I think, that historians are attempt to isolate the relevant variables, and that’s to engage in the comparative history of science. So, do we see science anywhere else in the world and what are the patterns, if any, that we see science undergoing there?

And the three classic comparatives for historians of science are Ancient Greece, Islamic science and China. There’s a very famous question asked by the sinologist Joseph Needham and it’s essentially this; ‘why did not science take off in China?’ And the question is particularly acute because China was ahead of the medieval west in terms of its technology. So, what is it that means that the west takes off in a way that did not happen in China? And we can ask the same question about Ancient Greece; they had science, they had a wonderful science going on there – what happened to it? Medieval Islam had a terrific science as well – what happened to it? And the analysis we tend to give is that what we see in cultures with science is a ‘boom-bust’ pattern, that science will for a time become important, there will be centres of scientific activity, there will be key scientific researchers, but that activity over a period of time will fade away. So, we get a little boom and we get a bust. And when we look at all other cultures in which we see scientific activity, what we see is a pattern of ‘boom-bust’, except for one so far and that is the west from the 17th century onwards.

14:17

And what we see there is not merely the origins of science, but crucially, the consolidation of science. So, what the comparative method enables us to do is to look for not what will give us a scientific boom, because those factors are actually common to a number of different societies, what we’re looking for is what will consolidate science. What will keep it there, what will push it into the middle of the culture so that it has really an unparalleled, epistemic authority, which I think for all the worries that science has, still remains true. It’s the activity in western society that people think is the best chance to give us a true picture of the world, and I think that still remains the case. How is it that after hundreds of years, that is still the case in the west in a way that was true for nowhere else.

And that question, I think, about the consolidation of science rather than just its origins, both are important. We need to have an initiation of scientific activity, but we need to have something that consolidates it. And what consolidates science is values. What consolidates science is a set of values because the society values science and it moves it to the centre of the culture and it gets behind it. And, to cut a long story short, what I’m going to suggest to you is that the key to the values that underpin the consolidation of science in the west are a set of Christian values. So, that’s to cut a long story short. We should be clear that this is not the whole story; there are all sorts of other variables here to do with the material conditions, to do with the varying fortunes of empires. So, there are certainly social, material and institutional conditions that are also part of the story. So, it’s over-determined, we’ve got lots of variables, but my suggestion is that the key to the consolidation of science in the West is a set of legitimating values that come from religion and that these are a necessary, if insufficient condition, for the consolidation of science.

16:40

So, I’m going to talk now about the ways that religion might influence science. But as you can see, the way I’ve set it up that this is going to be the one that makes the difference in terms of the long term consolidation of science. But let me just give you some of the other ways that science might be influenced by religion, in both positive and negative ways, but as it turns out, these are mostly positive; motivations, criteria for choosing between competing theories, presuppositions I’ll discuss in some detail, methods I’ll say something briefly about and then I’ll come back to this important question of how science gets consolidated and legitimated. So look, the motivations one is really quite simple and I was delighted that Alan put Kepler up there because Kepler is a wonderful example of how scientists are motivated by religious considerations. This is one key way in which religion feeds into early modern science. We get motivations to pursue science from a religious understanding of the world and so as I say, we’ve seen two examples from Kepler, here’s another one, pretty straightforward, you can read that for yourselves. I could have multiplied these examples beyond necessity, but I won’t, I’ll just give you Robert Boyle: ‘why do we study nature? Because we’re discovering the perfections of God in the world.’ So, we’re motivated to pursue science because we regard it as an inherently theological activity or it’s important theologically for us.

Newton is another one who is clearly theologically motivated to pursue science. So, this says nothing about the content or the presuppositions, it just says that I’m motivated to do this from religious considerations. It’s not universally for everyone in the 17th century that they have these strong religious motivations, they’re stronger in some than others. So, it’s not a universal picture but it’s certainly a key part for someone like Kepler who for me, I have to say, Galileo is the person that a lot of people talk about in terms of initiating the scientific revolution, for me, Kepler is more important. The formulation of those three laws of planetary motion which then Newton will come to bring together in the theory of the universal law of gravitation, the inverse square law. So, Kepler for me is the man, although it’s not a competition, but I’d like to see him get more due than he does. And of course, I think we all know Robert Boyle, you know Boyle’s law, etc. So, I won’t tell you too much more about him. So, motivations, it’s pretty simple, pretty straightforward, not universal but a pretty important factor.

19:24

Second thing: religion helps choose between competing alternatives, that’s one role that it can play. So, for example, what we have here … this is a famous book, the Almagest Novem, the new Almagest by Riccioli and this is a fantastic book because it brings together the three competing astronomical theories in the early modern period. We often only hear about two; the Copernican versus the old Ptolemaic, earth-centred model. But for a long time there was a third competing model, the Tycho Brahe Model where instead of all of the planets going around the sun, all of the planets went around the earth but the earth went around the sun. And what we see here is the three models; here is the old Ptolemaic Model which has now been discarded, here is the Copernican Model and here is the Tychonic Model; the fact that the Tychonic Model is weighing more than the Copernican Model suggests that it is the preferred model. And indeed, for a long time it was. Empirically there was little to choose between the Copernican and the Ptolemaic, the Ptolemaic was certainly slightly more complex but they both fitted the observations; the phases of Venus, the moons of Jupiter; all of the things that Galileo had used in support of the Copernican system, most of those worked as well for the Tychonic system and the Tychonic system didn’t have the problematic physics that you needed to get Galileo’s thing up and running.

So, why am I telling you all this? It’s an interesting example of what we call ‘the under-determination of scientific theories by the data’, because very often in science we encounter models that we can’t empirically separate and when we choose models then, we do it from non-scientific grounds. Aesthetic grounds are often used. In this case we can use religious motivations or religious grounds for choosing and indeed, the Jesuits for the 17th and much of the 18th century on religious grounds preferred the Tychonic Model. Now, we might say this was the case of actually religion motivating to choose the wrong theory but nonetheless, it shows you how religion can play a role when the empirical grounds are not there to choose between theories.

Let me bring us up to date; multiverse versus universe. The fine-tuning of the physical constants of the universe is a very intriguing fact about the cosmos, particularly if there’s only one. Now, one way around the puzzlement of the remarkable fine-tuning of quite a number of physical constants in the universe is to say there’s an almost infinite number of universes in which all of the variables have their particular values. So, there’s nothing particularly special about ours although it looks very special but it’s not special because it’s one of a large number. Why would we choose a universe over a multiverse? Well here again we see that non-scientific factors play a key role given that it’s difficult empirically to choose between these models. And so we see those who want to avoid the religious implications of fine-tuning will choose a multiverse and those who wish to argue that fine-tuning actually points to something a little bit like design will choose the universe. But I don’t want to labour this point too much, religion can play a role, to some extent positive or negative when the data is sufficient to help us choose.

23:19

But I’m more interested in these last three; the presuppositions, the methods and the question of legitimation. So, look I should have said at the outset that I’ll talk for maybe fifty minutes and so they’ll be time for Q&A at the end, if you have any questions then we’ll hopefully have time to answer them. Modern science has quite a specific set of presuppositions. For science to get up and running, we must assume the intelligibility of the universe. Now, the intelligibility of the universe might simply be a brute factor of how it is, but if you’re like Kepler then you believe that the universe has the intelligibility that it does because it was created specifically with a rational order. But in the 17th century, the order of the universe takes a specific form and that specific form is the Laws of Nature. Up until the 17th century, there were no Laws of Nature as such, there were some rules but the order of nature came from the inherent propensities of natural things. This was the Aristotelian view; that things did what they did because of an inherent propensity. So, the object falls towards the earth because things have a propensity to move towards their natural place and the natural place of things that have weight is the earth, which is the natural centre of the universe, that’s the old Aristotelian view. And things in the heavens of course, they don’t have that, they move in circles, it makes perfect sense.

In the 17th century, this view of the inherent properties of things is replaced by very different conception of natural order and that is the conception of Laws of Nature that are imposed from without. And they are imposed from without by God. So, René Descartes who you all know, ‘I think, therefore I am’, we think of him as a philosopher but he was a key figure in the development of modern science and part of this was the development of the idea of the Laws of Nature. So, here he is in his principles of philosophy which is really principles of science we would now say, here’s his understanding of how things move – God imparts motion. That’s the only reason that the inert particles move at all; God imparts their motion to them when he first created them and he preserves all this matter in the same way and the same matter in which he created them. So, for Descartes, not merely does the existence of things require God’s constant conservation which is a standard medieval theological view, but when things move, in essence for Descartes, this is God recreating them at every instant in a different location according to a particular rational principle or a ‘law’. So, the laws of motion for Descartes are God’s constant willing for every object in the universe, to behave in a particular way. That’s what a Law of Nature is, it is literally God imposing his will on matter at every instant, in a rational kind of way. That’s what a Law of Nature is.

26:24

And it’s precisely this conception that the English natural philosophers or scientists will then take up after Descartes in the 17th century. So, we’ll come back to Boyle. ‘Laws of motion’ he says, and he’s denying Aristotle’s view, ‘they don’t spring from the natural order of nature, they are not inherent in things but they depend on the divine will of the author of things’. That’s what a Law of Nature is, that’s why they move according to mathematical laws. So, mathematical laws again is a new conception of how nature operates; there aren’t mathematical laws of nature before the 17th century.

And to give you one more example, Newton also adopts this view and he has a famous quarrel with Leibniz, it’s not merely over who invented the calculus but over a range of things including his view of Laws of Nature. And Samuel Clarke takes up the fight with the philosopher Leibniz on behalf of Newton and here again he says precisely the same things about the Laws of Nature and this is Newton’s view: ‘the course of nature is nothing else but the arbitrary will and nature of God exerting itself and acting on matter continually’. Now, it follows from this then crucially, not merely then is nature ordered directly by God, in order to discover what nature is in terms of the laws, we can’t intuit them because God chose them, as Clarke has said, arbitrarily. So, God has chosen arbitrary ways for nature to work and given that, we have to explore nature experimentally in order to find out exactly what the content of the laws is. So, here in the preface to Newton’s famous work the ‘Principia’, this is the second edition, it’s explained not by Newton actually but Roger Cotes but Newton and Coates worked very closely together on the second edition of the Principia and here is the explanation: ‘the business of truth and philosophy [and remember philosophy means science for these guys at this point in time] is to enquire after the laws that the creator chose, not those that he might have done had he so pleased’. Now, that last bit is a bit of a dig at Descartes who had hypothetical conceptions of how nature worked and Newton said ‘we don’t deal in these hypothetical conceptions, we have to investigate nature closely and when we do, we see what laws God has imposed on it’.

So, the whole rationale for the Laws of Nature is intrinsically theological. So, summing it up, I’ll come again to Samuel Clarke because he’s probably the most philosophically acute theologian of the 17th century, he sums it up rather nicely: ‘there’s no such thing as a Law of Nature, really what Laws of Nature are is God’s constant willing’. Now, what’s interesting of course is that some time between then and now, and I can tell you when, it’s in the 19th century, the Laws of Nature which for these guys was God’s direct willing of events in the natural world, became naturalised and became a brute feature of the natural world and Laws of Nature became literally features of the natural world that seemed to require no further explanation. But that’s only happened because we have amnesia about the novelty of this idea of the Laws of Nature, we’ve forgotten about its theological origins and we now assume that it’s somehow a conception of the natural world that is, in itself, natural. It wasn’t then and we’ve just forgotten all this and that forgetting happened in the 19th century and it’s an interesting story of how it happened. So, what I’ve done here is to give you one example of how a particular scientific conception of how nature operates has fundamental theological presuppositions and that’s going to be a key part of how science happens and you can see obviously that the people we’ve been talking about are central.

30:38

We talk about the methods of science and this one is quite tricky I think. We’re going to go into a little bit of theology here, just a little bit but if you want to get the whole story of how the methods of science are informed by particular theological conceptions, you’re going to have to read that book but I’ll give you the quick and dirty version of the thesis and I’m hoping you’re going to get it. But the quick and dirty version goes something like this: as I’ve said before, science up to the 17th century was essentially based on Aristotle’s understanding of how things operated and Aristotle was not an ‘armchair scientist’ as some people have said, he was very interested in observation. But Aristotle, the observations were common sense observations and Aristotle had complete confidence, both in humans being’s capacity to sense what was going on in the world and to directly intuit the rationality of what was going on, that was his view. It was an uncritical understanding and as I say, it was common sense because if I drop this it will accelerate but if it’s a feather it will go like that, so Aristotle says that things that are lighter will drop slower than things that are heavier. It’s common sense observation, why would we not think that? We would only think that if we could think counter-factually and why would we do that?

Well there are theological reasons why we might do that interestingly. And let me just give you one more piece of information before I come back to the Protestant Reformation, Medieval scholastic thinkers had done a lot to bring Aristotelian thinking in line with religious thinking and they’d put together a wonderful synthesis of religious thinking and Aristotelian thinking. But as a consequence of that, when they read theological statements, they tended to interpret them in Aristotelian terms, that’s a vast overstatement but it gives you a bit of an idea. The Protestant Reformation comes along and the Protestant reformers say ‘you guys were misled by Aristotle and that’s made a difference not only to your theology, it’s made a difference to how you understand the world’ and I’ll give you some idea of how they’re going to say that. So, here’s Calvin and his commentary on Genesis and he’s talking about the Fall, and he says the corruption of our nature was unknown to the philosophers. So, Aristotle based all his science on the fact that he knew nothing of the corruption of human nature, he thought that human beings functioned optimally. Calvin’s saying ‘they don’t!’ Not only that, the corruption that happened as a consequence of the fall in not just our moral propensities and our cognitive and our sensory propensities and that’s what Calvin’s famous total corruption doctrine, it’s not that we’re totally rotten, it means that total deprivation means that every part of the human being is affected by the Fall. And that was not what medieval Christian predecessors had thought. They had not held that strong, strong view of the Fall.

33:51

Now it follows, and Luther’s going to make the point, that it’s impossible that nature could be understood by human reason after the fall of Adam because human reason was perverted. Did Aristotle know that? No. He assumed that our reason was reliable, our senses were reliable. But what happens if they’re not? How do you then approach the natural world? What difference does it make? So, this is going to be the key difference. Blaise Pascal, just to show you that it’s not just the Reformers, Pascal … again I probably don’t have to labour the point that he was important to the development of science, but interestingly what he has in common with the Protestant thinkers is a strong Augustinian understanding of human sin and frailty and the Fall. And again, here he’s saying the same thing that Luther and Calvin are saying, that the philosophers, if they knew the excellence of man, they didn’t know his corruption and they were over-optimistic or they fell into the opposite camp and they became completely sceptical. And they became completely sceptical because they hadn’t understood that Adam had once possessed a very good scientific knowledge of the Fall.

So, human beings find themselves as Blaise Pascal and Calvin would say, between an original condition where we knew because of our reasons and our senses were perfect, we had a perfect scientific knowledge of the world and we’ve fallen away from that and Luther would say a knowledge of the world was impossible and a scientific knowledge of the world as Aristotle understood it was indeed impossible, but some form of knowledge of the world was possible and that was an experimental knowledge and that really then will become the key to a scientific understanding of the world. So again, Pascal, ‘we possess an image of truth, we know we were made for truth but at the same time, we suffer the consequences of the Fall: ignorance. So, we know that knowledge is possible but we also know that in our fallen condition we can’t actually get there. And science is going to appear in the tension between those possibilities and I’ll show you exactly how in a minute. But I’ll just give you one more example, here’s Francis Bacon again, not much of a scientist himself but a key figure in the development of modern science, understanding the methods of science. The human intellect is not to be trusted and crucially, nature itself is fallen. Nature is hard to understand because it too has a fallen condition and so all we’ve got to rely on is the uncertainties of our sensory apparatus, which are ourselves fallen.

36:36

So, is there a bit more? Yeah. So, what we’re trying to do, says Bacon, when we do science is to see if we can connect up this great commerce between the mind of man and the nature of things which once existed in a perfect condition. So, what are we trying to do with science? We’re trying to see if this original connection between human beings, minds and senses and the world, can we get there again? Is it possible? And if it’s not possible to restore it to its perfect original condition, can we get it to a better condition than it now was? And what this is going to require is a very different project from the Aristotelian uncritical and thinking it’s all easy because it’s not. Whatever this is, it’s going to be really hard and that really is the trick to the new experimental science.

Let me jump to the conclusion then and here it is: Robert Hooke, this famous book Micrographia has got these beautiful drawings from under the microscope and he is the first curator of experiments of the Royal Society and part of the justification for using instruments like the telescope and the microscope is the understanding that our senses can no longer be relied upon to give us good information. But he just lays it out here: ‘we have a derived corruption innate within us. Given that, these are the dangers of human reason, the remedies can only proceed from the real and the mechanical and the experimental philosophy.’ And by ‘experimental philosophy’ he means a new way of doing science that is experimental. And what are the characteristics of that?

Well as I say, you’re going to have to read the whole thing but just to give you an understanding of how this is suppose to work, in light of this theological anthropology, we can never arrive at certain knowledge of the world. That’s what Aristotle thought but we can’t but we can get probabilistic knowledge. We only have knowledge of the appearances of things, we can’t penetrate for their essences. Crucially knowledge is corporate; you have to have lots and lots of people working on it and it’s cumulative for a long time and you need to accumulate this knowledge. So, you can’t have this single genius like Aristotle just working it all out, it has to be a corporate activity and it has to happen over time.

It’s got to be based on experience rather than reason, we can’t trust reason and therefore it has to be an experience. In the Latin, experimental and experientia are the same thing, and indeed in England, experimental meant experiential. So, interestingly, in the 17th century this is a topic for another paper but the chief context in which the word ‘experimental’ is used is in a religious context: experimental prayer, experimental religion, experimental reading of scriptures. And what they mean by that is experience based. And there’s actually an important link between these religious uses of experimental and the scientific uses, but that’s another story. Fallen senses are augmented by instruments; this is the first time we have the telescope and the microscope used; you have to investigate nature aggressively because nature is fallen and it’s hard to get information out of nature. So, experiment is intrusive, you can’t just observe nature as it is, you’ve got to get in there and change it. And this again was completely contrary to what Aristotle had taught.

40:05

And all up, the whole scientific approach is meant to be a kind of therapy that we apply to overcome the inherent limitation of reason and the senses. So, that’s the short version of the story of how a new experimental approach is underpinned by a theological anthropology and it all lines up. But I won’t labour the point, as I say, it’s just another example of how this theological point becomes crucial and these guys are all talking about it and it tends to be overlooked.

Okay last thing and we’ll get to this question of moral legitimation and I don’t want to say too much about this. This is another one that can be really hard to get, but let’s start off with the premise that when science gets up and running in the 17th century, it’s not the glamorous, reliable activity that we now think of it, it struggles to get recognition and if you want a good example of this, read Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels, his stories about the Grand Academy of Lagado where he mercilessly satirises the activities of the Royal Society and there are a lot of works where the Royal Society is held up to ridicule because no one thinks that what they’re doing is useful and they have this knowledge. What on earth are you doing? What is useful about what you are doing? And they would say well we’re doing these practical things. And they would say things like the blacksmith and the baker do practical things, surely your activities are more dignified than these crude people providing these crude material needs. And again part of the background here is that part of natural philosophy or science as we would call it, was really meant to be about the elevation of the individual, that’s what the aim of natural philosophy was.

Now, there’s a long story there that I can’t get into but you can take my word for it. So, in this context, 17th century science looks like a kind of trivial activity … humanities are where it’s at, STEM [Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics] is not where it’s at, it’s all about the humanities. And STEM has to justify itself, it’s kind of around the other way to some extent now but that’s another story. So, given that, how is it that science makes the case for its usefulness? And it’s not merely usefulness in our terms, what has to happen is it actually has to change our very conception of what counts as useful, that’s going to be the key thing. It has to change what it is that we value as useful and it’s going to do that by means of religion and in a way to some extent that I’ve already outlined.

But just to give you a perspective from the 19th century on that, we’re talking about Bacon, and McCauley is saying ‘what difference does Bacon make to how science is done?’, and here he says ‘up until Bacon, the ancient philosophy of science, it disdained to be useful in practical terms and dealt largely with theories of moral perfection.’ And that’s exactly right because moral perfection was regarded as more important than provision of practical necessities. The moral perfection of the individual was thought to be more important than the provision of practical necessities. Still to me an open question, but there it is. But Babbington says ‘no, we’re not interested in moral perfection. What we’re interested in is all the practical benefits that science can give us.’ Again, seems to me there’s a judgement call there, it’s not obvious that that’s how we should go.

How do we persuade people that that’s how we should go? Well here’s Bacon and he’s going to make this point: ‘We’re not seeking knowledge for the quiet of resolution for meditative purposes, but’, and here the kicker, ‘the religious justification for the pursuit of knowledge,’ and again it comes back to the point that I’ve already made to some extent, ‘is to restore to human beings the sovereignty and power that we once enjoyed in our first state of creation.’ So, what Bacon wants to say is ‘we can achieve some degree of moral perfection and that’s the role of religion but the other thing that we lost when we fell was not merely our moral status but our control over nature.’ And so science is aimed to re-established an original dominion over nature that we lost as a consequence of the Fall. So, why are we engaged in these practical activities? Because it’s a redemptive activity intrinsically that restores to us the power that we have over the creation. So, there it is; ‘creation was not by the curse made always and forever made a rebel, but now by various labours’, that is to say this new scientific approach, ‘will be subdued to provide us with the uses of human life’.

45:12

So, we get a division between the aims of religion, which are to restore in part our moral perfection and the aims of science which do the other bit, which is to re-establish our dominion over creation. So, a key way in which the activities of science were legitimated were for Bacon to roll it into this redemptive exercise. And there’s one more that I’ll give you and then we’ll wrap up because you’ve probably had enough by then.

The other one is a very straightforward theological justification that says that in this way of doing science, we actually discover what it is that God has done in the world. So, it’s the old motif of the Book of Nature where we learn about God’s power through studying what he’s done in the natural world. And again, this becomes … I’ve just given you two key examples here; Boyle and Isaac Newton. To sum up how this works, it’s about natural theology, which is to say studying nature teaches us about God’s design in the world and hence it is to some extent a theological activity and that’s why we ought to do it. And while the Fall motif of restoring sovereignty over nature was a powerful motif in the 17th century, for the 18th and 19th Centuries, natural theology was a key part of what it is that science was understood to be doing and indeed natural theology was the key mechanism through which science was popularised to lay audience, certainly in England in the 18th and 19th Centuries. People learnt their science through studying works of natural theology. And that’s why, for those of you who were at the last lecture, the question about the legitimation of science now in the present I think remains a really interesting question. Because I would argue that without a set of values outside it, science will lack social legitimacy and we see science’s authority being questioned now and it will be interesting … my question would be whether it is at least in part because we no longer have this rich set of ideological underpinnings for the reasons that we value science.

So, very quickly summing up, when we try to explain the rise of modern science, we’re engaged in a very complicated process and there are lots of variables. I focussed on one set of variables which are the religious ones, but I think they are necessary, if insufficient, and they operate in a number of ways, they motivate individual scientists, they provide key presuppositions in terms of laws of nature, they provide an underpinning for quite specific and again a quite special and unique experimental approach to investigation, and finally religion has provided the values that have meant that science has had social legitimacy for quite a significant period of time. And as I’ve said, it’s these distinctive features of science that set it out from anything else that happened, either in other cultures or in the pre-modern history of the west. And I think I’ll stop here, thank you.

48:35

[Applause]

QUESTIONS

PETER HARRISON: So, I think we have a roving mic, is that right?

CHRIS MULHERIN: We’re recording tonight, so we’re going to try and record the questions as well.

QUESTION 1: Peter, thank you for a fascinating and stimulating address, it was remarkable. You spoke about the boom and bust patterns, you spoke about the need for values to consolidate (I think was your word) on science and you touched very briefly on this at the end, so what is one to think then of Postmodernism? Is this the beginning of a deconstructing of the values within which modern science presides and if the answer to that is yes because it’s challenging the existence of truth, how does one think about Postmodernism? Is it anti-scientific?

PETER HARRISON: Right, it’s a … Well it’s interesting because we’ve got the Postmodernism question at the last talk as well. Look, it depends what you mean by Postmodernism and I think if you mean a kind of insipient, relativism … Look, I don’t think that any particular philosophical program, let’s call it ‘Postmodernism’, is going to explain much. I think rather, Postmodernism itself is going to be symptomatic of the set of problems about legitimation. So, I think the causal arrow would be the other way around, that Postmodernism is the kind of thing you get when you move away from a foundationalism that is epitomised in someone like Descartes. And if we take foundationalism as being the view that our knowledge is built on a set of foundations and built up in there from some systematic way, such that it’s possible for critique to occur within the general kind of neutral framework, it’s hard to make that work without theological foundations I think. So, Postmodernism is really in a sense, a realistic facing up to what you get if you no longer believe in those sorts of underpinnings. So, if we take Nietzschean ethics for example, so Nietzsche well proceeds Postmodernism but he could be seen as a harbinger of it, but Nietzsche’s ethical theory is precisely what you’d get if you don’t believe that there’s some basis for natural law or theological understanding of the virtues or a conception of the common good, all of which need to be grounded in some over-arching metaphysic … Sorry, it’s a very long and complicated answer to your question but yes … So, to cut a long story short, I think Postmodernism is symptomatic of a more general issue which is to do with whether you can get anything up and running without some kind of fundamental theological commitments?

52:54

QUESTION 2: Thank you. You mentioned ‘all truth is God’s truth’, now I’ve heard that in Calvin in the 16th century, was there anybody before that time who spoke in a similar way?

PETER HARRISON: Look, I would imagine it’s a common … I imagine this is common in the Christian tradition, I mean all … the trick of course is to know what those truths are, that’s where the debate always takes place.

QUESTION 2: I think Calvin was thinking about science.

PETER HARRISON: But again I think … Presumably what Calvin means by that is in so far as scientific truths are, God is the author of the Book of Nature, what must be true about nature can’t be inconsistent with what God has revealed to us and in that sense, he’s talking about a distinction between revealed truths and the truths of nature, and in principle, and who could disagree, they must be in harmony. But if science is your measure of what’s happening in the natural world, it’s still up to grabs as to whether science has got it right or not and of course there are going to be discussions about what count as genuine revelation. This was precisely that the Protestant Reformation itself precipitated by insisting on Sola Scriptura, you then have the question of the interpretation of Scripture, which I think then becomes a problem that’s essentially insoluble. It’s insoluble unless you have a Catholic view that the Magisterium does the interpretation and everyone else does the listening. Anyway, perhaps I shouldn’t be wanting to advocate that too strongly but … sorry, I guess what I want to say is that the principle is a great one but once you start to try and figure out what will follow from it, I think you still end up with the issue … so, we say that in principle there should be harmony but when you work out the details, that’s where the problems are …

QUESTION 2: So, you don’t know of any other medieval …

PETER HARRISON: Well they certainly did because you’ve got the conception of the two books which goes right back to the church fathers and I think the conception of the two books is really the … is a way of stating the same thing in another way. But they’re also acutely aware of the problem. So, Augustine in the 5th century is going to use the metaphor of the two books; the Book of Nature and the Book of Scripture; but Augustine will also say that when an interpretation of Scripture contradicts a demonstrated truth of natural philosophy or science, you must give up the literal interpretation of Scripture. So, that’s the outworkings of the ‘all truth is one’ principle where you have to adjust how you understand the revealed tradition in light of a demonstrated truth of natural philosophy. Now again, the complication there is that Augustine is working with an Aristotelian philosophy of science which thinks that you can actually get demonstrated truths and after the 17th century no one really thought that anymore.

56:31

QUESTION 3: Thanks for a great lecture, that was wonderful. would you comment on David Nobel’s book, ‘The Religion of Technology’, because he likewise that a Christian imaginary both underpin both the emergence of science but also has continued in kind of a covert way the ongoing development of science, the point that you were making about boom and bust. He likewise picks up the fact that Bacon and before him Roger Bacon and others saw the new experimental science as a way of overcoming the effects of the Fall, either restoring Eden or moving to Paradise. But his is a negative view rather than trying to show that Christianity was an important factor, to show that in fact our current dilemmas with modern science actually have their roots in this desire emerging out of Christianity to overcome our mortal condition and move towards divinity. But interestingly, he argues that many of the major projects of contemporary science; artificial intelligence, genetic engineering; are still fuelled by that kind of millennial aspiration.

PETER HARRISON: Yeah, you make a good point. And so there are two sides to this. You say well Christianity plays a key role in the emergence of modern science, is modern science an unvarnished good? You might say that but if it’s not, then Christianity also to some extent on this account has to take the blame for any of those aspects of it. Now, the most conspicuous statement of this thesis is Lynn White Junior’s famous paper in Nature in 1968 where he said that Christianity bears a huge burden of responsibility for the ecological crisis. Why? Because it emphasised the conception of dominion over nature. Now, in a sense … So, what am I saying here? My argument is that this notion of dominion over nature does in fact play a key role and it plays a key role in the emergence of modern science. There’s the tick, there’s the up tick on the positive side. There is something to Lynn White Junior’s argument, that these notions of dominion can then run wild and if you trace back the historical origins, then that’s how it looks.

But the other part that you say which I think is quite interesting is the eschatological because I didn’t talk … There are Baconian conceptions which are highly eschatological, so the frontispiece that I showed up there actually has a quote from Daniel, “many shall go to and fro and knowledge shall be increased” and this was to happen at the end times. So, as you point out, it was not merely a harking back to originally perfect condition where we had dominion over nature but a future state. And the motivation for pursing science for many people in the 17th century was to restore the world in preparation for an imminent eschaton. So, there’s a very interesting eschatological conception. Now, once you secularise that eschatology, then you get some … And I think the trans-humanism, post-humanism, these are all really quite interesting forms of what you might say ‘Christian eschatological heresies’ would be one … they wouldn’t welcome that description but I think it’s quite apt and it’s very interesting. But I’m not familiar with the book and so I must read it by the sounds of things, yes.

60:05

QUESTION 4: Dr Harrison, I was just wondering if you might be able to clarify the two-book metaphor because I recall reading, I think it’s in The Advancement of Human Learning, that Bacon actually cites the two-book metaphor. And yet in the one that you’ve given us from Novum Organum, you suggest that he sees man as having a measure of power restored to him in a redemptive sense. And I’m just wondering where in the earlier statement that he made where he refers to the two-books, it seems as though he’s referring to general revelation but in this one it seems that he’s referring to God’s common grace and if that’s the case, they’re quite different categories. Do you get what I mean? I mean I hear modern scientists quoting Bacon in the first quote and saying that scientific discovery is part of God’s natural or general revelation and you’re quoting the second quote tonight under social and moral legitimation, almost as a category of common grace which is a different kind of category and I’m just wondering how carefully nuanced Bacon was in advancing the idea of the two-book theory?

PETER HARRISON: Okay, look he was pretty carefully nuanced. The reference that I haven’t mentioned is and I can’t bring it to mind I’m afraid … what he says is ‘there are two-books from which I derive my divinity’ but the lesson that’s usually taken from that quote … he goes on to say ‘they should not be unwisely mingled’[1] and that’s often taken to read as Bacon was using the two books as a metaphor to advocate a separation of science and religion. But I’m afraid, I can’t bring the specific … I know the quote you’re referring to but I just can’t bring it to mind and I can’t actually recall how it’s typically read … Look, Bacon is a very sophisticated thinker and he can sometimes be quite difficult to get hold of … But his theology seems clearly to me to be Pelagian, what he’s suggesting is a process of redemption that we get through works in essence, and so he’s strongly influenced by his Calvinist mother but he nonetheless has this strong Pelagian conception of working towards redemption in this material and practical way. What his views are about common grace versus general and special revelation … he’s pretty sharp theologically so my hunch is that he’s probably got it right but the categories … I mean common grace is really a kind of Calvinist expression, correct me if I’m wrong, and I’m not sure he’s operating with that idea. I think at the back of his head he’s thinking more general revelation versus special revelation.

63:50

QUESTION 4: A lot of people though today refer to him to appropriate his idea and suggest that scientific discovery falls into the category of natural revelation. So, I’ve heard Francis Collins about five months ago use exactly that quote in a very large public meeting and an array of speakers afterwards, all of whom were professors said exactly the same thing and it sounds from what you’re saying tonight that it may not fit into that category at all.

PETER HARRISON: Yeah, I mean I’d be reluctant to go up against Francis Collins, he’s a very good geneticist … I’ll take it on notice and I’ll be very interested to look into it. I’ve got all of the Bacon quotes on the Book of Nature, I know them and I’ll be interested to look at them in light of what you’ve said.

QUESTION 5: Thank you very much, I’ll interrupt the Baconian discussion here and go back to an earlier point you made here about the boom-bust cycle of science in other cultures. I’m not sure if you’ve studied it much, but what are your views as to why the medieval Muslim culture failed to develop consolidation of science as distinct from the Christian culture of the 17th century and what are the features of the Muslim culture that were inimical to the consolidation?

PETER HARRISON: Sure, it’s a good question. So, in terms of lack, what I would say is that they don’t have a theological anthropology like this, they don’t have a conception of … The Laws of Nature is a really interesting one, I was going to say that they don’t but in a way they do, I’ll come back to that. And there are a lot of material conditions and there are institutional factors and there’s an attitude to ancient sources.

65:52

Let me start with the attitude to ancient sources. There’s a very interesting difference between how Islamic culture deals with its sources and how Christian cultures deal with its sources. And so Islam was all over the Greek natural philosophers, they translated into Arabic and then they just got rid of it. So, when the Christians encounter the Greeks initially through Arabic translation, but they are interested in the Greek culture for its own sake. And just as the Christians preserve the Hebrew Bible intact and indeed it was a heresy to say that the New Testament had completely superseded, that wasn’t – that was Marcionism… So, in Christianity there was a really interesting attitude towards ancient texts and the preservation of them intact as culturally representative. So, Islam is interested in them but once it’s absorbed them, it discards them. So, Christianity always has the possibility for an ongoing conversation with the preceding culture because it’s interested in the original sources, in the original languages. And that’s why the Protestant Reformation can go back to the New Testament and can go back to the Old Testament and that’s why the scientific revolution can go back to the original documents. And that conversation gives dynamism to western culture that you don’t see in Islam. So, that’s one interesting factor.

Institutionally the West gets universities from I think the 12th century on and the universities are, I think, these are going to be institutional powerhouses of knowledge and learning that we don’t see anywhere else. Now, interestingly of course, there are Ecclesiastically supported, so religion is a factor there, but if we look to material factors like the institution, that’s another reason. Some people argue that the legal framework of Islam is not suited.

The interesting one I think though in relation to Laws of Nature is that Islam does actually have possibility to get an idea of Laws of Nature up like this and in fact the Ash’arite theologians had a conception of the Laws of Nature as directly dependent on the will of God, but what was really interesting is that the mainstream Islamic tradition was Aristotelian and they denied that this was the right way to think about nature because they thought that if everything at every moment relied on God’s willing it, they thought that would make science impossible. That was the argument coming from an Aristotelian framework and it’s precisely that view of the divine will in the 17th century that actually gets us Laws of Nature. There was an interesting thing in Islam about presuppositions but it was resolved, interestingly, in favour of a view of Aristotelianism although that strong voluntarist tradition prevailed.

And I mean, the other thing I think you can say is that politically what happened to the Arabic civilisation, that it was so dispersed and it underwent political change that meant the kind of consolidation was impossible. So, in a sense I’ve contradicted my own argument by giving you a whole lot of other reasons why it didn’t consolidate, but I guess what I want to say is that these things are never mono-causal and there’s always quite a variety of different reasons and that’s what I want to say. I think the religious things, I think they’re necessary but they’re insufficient and there’s always more than just the ideological factors that are involved and these practical, institutional things are part of that.

69:30

QUESTION 6: My question was about what other factors contributed to the development of the scientific revolution. You’ve partly answered that but I’m sure you have more to say. What are the factors in western culture?

PETER HARRISON: So, again you want me to contradict the previous argument and give you reasons not to believe what I’ve just said. Well again, as you can tell, the recovery of certain aspects of Greek thinking is going to be key and if we think here … one presupposition of the conception of the Laws of Nature is that the natural world is made up of innate particles. And this is essentially an Epicurean Democritian atomism that’s recovered in the 17th century. But interestingly, it’s Christianised because atomism was always associated from Antiquity on, with atheism. So, the contemporary 17th century revival of atomism has got a theological problem and it’s got to somehow make atomism be religiously respectable and Laws of Nature is the way it does it because it puts God in direct control. And so part of the PR job that advocates of atomism have to do is to show that it’s not insipiently atheistic. So, that’s part of the story. So, the Greek tradition is still playing an important role and the medieval tradition of course is there as well. What else have we got?

QUESTION 6: Social factors?

PETER HARRISON: I mean you need a degree of political stability for these things to work … interestingly you’ve still got the lingua franca of Latin, so the communication will work. And once you get institutions and once you get strong institutional bases … and that’s part of the corporate or cumulative aspect of those. And so, once you’ve got those, then you’ve got a degree of stability, even if France and England are at war … it’s interesting that you’ve still got scientific communication that’s possible. So, you’ve got those networks of communication that are also key. The eschatology I haven’t talked about, but we’re getting back to religious things there. But look, if you want a view that doesn’t really look at religion at all, H. Floris Cohen has written a book called ‘How Modern Science Came into the World’ and he’s a very good historian but he doesn’t talk about these religious themes at all, and I think that brings together a lot of scholarship around how the scientific revolution happened, but it’s not great on the religion side of things.

CHRIS MULHERIN: Thank you Peter, we’ll take one more question.

72:57

QUESTION 7: Peter, I wonder whether one of the reasons why science is flourishing in the west is because it’s open-ended as oppose to being self-referential and referring back to the origins all the time? I’ve got in mind Stephen Jay Gould’s comment about Bacon’s paradox whereby you’re truly wise if you mimic the ancients and of course Isaac Newton’s comment that ‘I know more because I’m standing on the shoulders of giants’.

PETER HARRISON: Look I don’t know enough about the sociology of modern science to know whether that’s even true that it’s open-ended because it seems to be the question of curiosity driven versus utility driven science …

QUESTION 7: Well, we’re always discovering new things and you’re always sort of forging the boundaries of ignorance to knowing more and discovering more and getting a PhD in the process and then articles and all those sort of things …

PETER HARRISON: I mean what you’re suggesting is that science can be self-legitimating and part of its self-legitimation is its open to curiosity.

QUESTION 7: I mean I’m thinking of sort of traditional worldviews. I mean the example I had in mind is a student in India who from a Hindu background thought he was doing the right thing by mimicking my thinking and he had no idea of going out and experimenting and proving my thinking. The closer he got to being what his guru believed, the more right he thought he was and that means that this is a closed system as oppose to an open-ended system where we are both learning together and the teacher can learn from the student.

CHRIS MULHERIN: That is it, thank you very much Peter.

[1] [The quotation is: “To conclude, therefore, let no man upon a weak conceit of sobriety or an ill-applied moderation think or maintain that a man can search too far, or be too well studied in the book of God’s word, or in the book of God’s works, divinity or philosophy; but rather let men endeavour an endless progress or proficience in both; only let men beware that they apply both to charity, and not to swelling; to use, and not to ostentation; and again, that they do not unwisely mingle or confound these learnings together.” Bacon, Francis. The Advancement of Learning, Complete Works of Francis Bacon (Kindle Locations 703-706). Minerva Classics. Kindle Edition.]

Thanks to Ridley College for their ongoing support.