Originally published in Eternity News.

ISCAST opinion articles invite writers to share their perspectives on various science–faith topics to generate a constructive conversation. While ISCAST is committed to orthodox Christian faith and mainstream science, our writers may come from a range of positions and do not represent ISCAST.

The industrial revolution of the 19th century and the information technology revolution of the 20th century will soon be overshadowed by the human revolution of the 21st century.

This present century is likely to bring about a self-directed transformation of human functioning that will modify the nature of the human person in a way that will have a far greater significance than either of these previous revolutions.

This will almost certainly come about as the result of the convergence of a number of technologies and advances in knowledge that will coalesce around human life in ways that were previously unimaginable. This transformation of the human person began in the 20th century and we are now familiar with the use of pharmaceuticals, surgical interventions, implants, prosthetics, bionic ears, pacemakers, organ transplants and so forth that already influence physique, emotion, thought, personality, gender, and behaviour.

We have also seen the development of artificially created embryos and the use of donors and surrogates. Medical technology has become efficient at enabling people to live longer, healthier lives. Gene technology not only enables the re-design of agricultural crops but also of humans. Through the powerful combination of reproductive and genetic technologies the notion of ‘designer children’ is possible.

Reproductive technologies give rise to the possibility of human cloning and others are working on producing life from proto-cells, attempting to create life in the laboratory from cells with lifelike properties created from non-living materials.

The average human lifespan has increased as the result of numerous medical developments. But well beyond this there are those working on the fundamental processes of ageing who aim at radically increasing the human lifespan.

Developments in artificial intelligence have recently come to the fore and will continue to be significant. There is then the possibility of directly enhancing (or perhaps diminishing) human thinking by such artificial means. Developments in genetic manipulation and DNA computing may well converge with other developments in artificial intelligence.

Intellectual enhancement, genetic modification, radically increased lifespan, reproductive transformation, and emotional and physical modification all give rise to the possibility of the merging of the human with the machine, and the potential blurring of species.

The essential point is the cumulative effect of these technologies. Individually they are all important, but when these developments coincide the impact is profound. It is possible there will be a shift from the present situation whereby modifying and manipulating existing human nature is possible to the situation where there is a more comprehensive and intentional self-directed form of radical human transformation which challenges the boundaries of human nature and the future form of the human species. The concepts of ‘human’, ‘animal’, ‘plant’ and ‘machine’ are all concepts that will evolve and, in some respects may merge together. Clearly, the limits of human-ness will be tested.

Individually they are all important, but when these developments coincide the impact is profound.

Consequently, the theological question of what it means to be human needs to be discussed anew. To what extent should the species homos sapiens direct its own future development? How are we to understand the nature of human relationships with other species and with artificial, mechanical and other biological entities? And what role do theological concepts such as the imago Dei—the image of God in humanity—play in assessing the appropriateness of such changes and transformations? What is the appropriate role of human creativity when it comes to modifying humanity?

Questions relating to genetic enhancement and the development of artificial intelligence need to be addressed by Christians, and this needs to be done now.

Is it possible to avoid the extremes of optimism and pessimism concerning these new technologies that produce either messianic expectation or a dystopian nightmare? It is by no means certain that scientific optimism concerning human advancement is always appropriate. It is possible that new technologies will impact humanity negatively. Frail and sinful humanity may simply find new ways of damaging society, engaging in war, mistreating others, and making morally damaging errors.

But, equally obviously, ignoring the possibilities inherent in the new technologies and failing to trust in the providence of God could lead to a denial of life-enhancing changes that will enable significant benefits to emerge.

Questions relating to genetic enhancement and the development of artificial intelligence need to be addressed by Christians, and this needs to be done now. ISCAST is an organisation that is committed to an ongoing dialogue between science and Christian faith and it is exploring these issues at a one-day, in-person conference, The Scientific & Spiritual Human on 22 July at Trinity College Theological School, Parkville, Melbourne. See iscast.org/human2023. It will be led by an impressive lineup of experts from various fields on how faith can speak into being humans of the future.

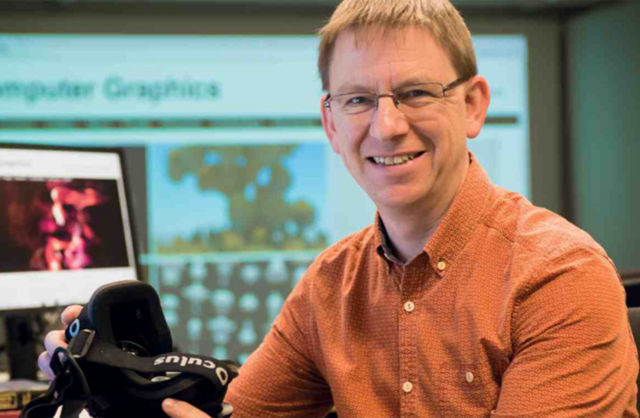

Dr Brian Edgar is a fellow of ISCAST where his teaching focuses on integrating theology with other disciplines such as science. Before becoming Professor of Theological Studies at Asbury Theological Seminary, he worked as the Director of Public Theology for the Australian Evangelical Alliance and as Academic Dean at the Bible College of Victoria. He was also previously a member of the Federal Government’s Gene Technology Ethics Committee.