Originally published in The Melbourne Anglican.

At ISCAST’s recent conference The Scientific and Spiritual Human, Dr Mick Pope presented on how the book of Revelation helps us grapple with climate change. This article is based on this presentation, which you can watch here.

Where do we go for a theology of climate change? One answer is to the book of Revelation.

We are living in a climate apocalypse—the end of the world—aren’t we? Some look to the scientific data to support this. For instance, computer models of current ocean oxygen levels match those during the Permian extinction 251 million years ago, when 96 per cent of marine species suffocated.

For some, the book of Revelation and the term “apocalypse” go firmly together—it’s all about the end of the world. But, in Revelation, God’s plan for creation unfolds as a return to the beginning.

Revelation is not a script for a Hollywood disaster movie. “Apocalypse” doesn’t mean “destruction” but “unveiling.” To rediscover God’s plan for creation in this book, three questions will guide us: What does the book unveil? What does our current climate change unveil? And, how does the drama of Revelation guide us through the climate catastrophe?

What does Revelation unveil?

Revelation reveals that God is making all things new, that God is in charge, and not the empires of the world. The following four ideas help us to appreciate this.

Firstly, Revelation was not written to us. It is a letter to seven churches in Asia minor. That said, it is written for us.

Secondly, Revelation is fundamentally anti-empire in intent. For example, the church in Smyrna was divinely encouraged during oppression from the empire (Revelation 2:8-11). This church was poor because it refused to embrace the imperial cult of worshipping the emperor Domitian as divine. They were excluded from trade guilds where Caesar-worship was part of business. Likewise, Revelation’s throne room scene (Revelation 4) was inspired by real world events involving the king of Armenia and the emperor Nero.

Revelation’s anti-empire polemic is not surprising because Rome treated the natural world and the non-elite as fuel for the economy. Ancient History Professor the late Keith Hopkins observed that Rome lived in luxury, and the rest of the empire in poverty. In Revelation 18, Rome is depicted as a “home for demons” and in chapter 17 as a prostitute, with whom the kings of the earth fornicate and live in luxury. Merchants and traders are identified for their complicity.

Thirdly, we misapply Revelation to today’s world if we make the empire about someone else. The empire is us. While our destruction of the earth has increased exponentially since the 1950s, the ideological origins that drive this destruction go back to the age of settler colonialism. This age was defined by new technology, dispossession, genocide, environmental destruction, and slave labour. Modern climate change is a symptom of a worldview that assumes nature and others are resources for our restless economic system.

Modern climate change is a symptom of a worldview that assumes nature and others are resources for our restless economic system.

As far as our systems serve destructive ends rather than the common good, these “powers,” as theologian Walter Wink identifies them, are demonic. With this interpretation, fossil fuel companies that have lied or manipulated the truth about the impacts of their products, and the structures that maintain their hegemony, are demonic.

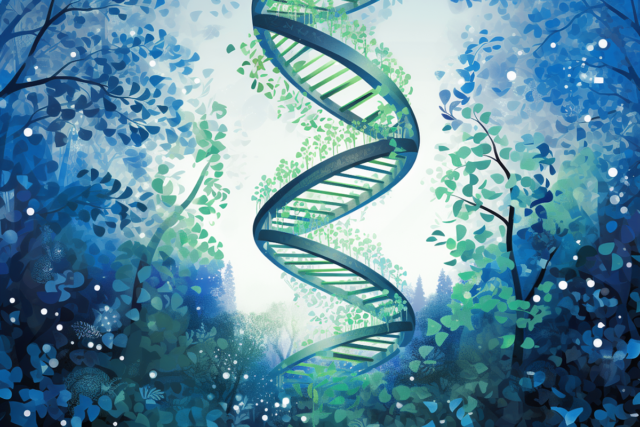

Lastly, Revelation is not about going to heaven when we die while the world is destroyed. Chapter 21 depicts heaven—the presence of God and Jesus—coming to earth: a rapture in reverse. Like changing scenes in a play, the old heavens and earth pass away to reveal that God is making all things new.

What does current climate change unveil?

If God is making all things new, humans seem good at trying to undo these efforts.

Christian ethicist Michael Northcott draws the link between ecological disaster and unfaithfulness to God’s commands, as he comments on the destruction of Jerusalem in Jeremiah in A Moral Climate: The Ethics of Global Warming. Northcott argues that the late Israelite monarchy and the merchant class placed “excessive ecological demands on the land.” He claims that justice is a concept embedded into the fabric of creation itself, where we are “caught up in a nexus of relationships” which include … the human, nature, and the gods.

This understanding echoes the views of Ewa Bińczyk and Dipesh Chakrabarty who argue that we are embedded in a “planetary metabolism” exercising our own climate-changing “hyperagency.” This agency has turned the metabolism against us.

How does Revelation guide us through our climate crisis?

If we accept that God is making all things new, despite how the world seems now, are we helpless bystanders?

Here, the “sea” in Revelation is a key theme because it has relevance to current climate change. In Revelation 13 the sea is the origin of blasphemous Roman power—the beast with 10 horns. Similarly, in Genesis 1 and the flood story, the sea is the personification of chaos and destruction. Gale Heide argues that the removal of the sea in the new heaven and earth in Revelation 21:1 simply means that the “old order/system and the power of evil have been removed from John’s sight.”

The concepts of “sea” and “chaos” are further developed by the idea of Sabbath. Genesis 1 describes a six-day creation without opposition or violence, compared to the stories of Israel’s contemporaries. The watery chaos is ordered so that human and non-human alike might be provided for. The seventh day is declared holy, a day where God rests from the work of creation, providing rationale for Sabbath-keeping for Israel. Hence, Jewish scholar Jon Levenson argues that Sabbath-keeping—letting the human and non-human alike rest from our economic labours—is imitative of God and a way of maintaining creation and keeping chaos at bay.

Far from being helpless bystanders, while we wait for Jesus to return to bring peace and order, we have things to do and a Sabbath-ethic to adopt. Technology will not be enough to avoid the worst of climate change without a Sabbath ethic—one that de-emphasises economic growth and gives the earth time to heal. As environmental lawyer Gus Speth once noted, our environmental problems are not, at the root, biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse, and climate change. They are selfishness, greed, and apathy.

Our environmental problems are not, at the root, biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse, and climate change. They are selfishness, greed, and apathy.

The gospel addresses these things. Jesus proclaimed the Jubilee year, or “year of the Lord’s favour.” Revelation looks forward to the peace of Eden and healing for the nations. To suggest that the church sits back while political and climate chaos proceed apace seems disobedient.

British intellectual Terry Eagleton, in Hope Without Optimism, describes the gospel narrative over and against a capitalist one:

The kingdom of God brings to fruition a pattern of transfigurative moments immanent within it, a fractured narrative of justice and comradeship which runs against the grain of what one might call its central plot.

These “transfigurative moments” will be found with people of good will, who follow God’s good justice embedded in the world even without a faith in God. How tragic it would be if the church, rather than living out such transfigurative moments, would rather serve empire.