A new kind of genetic determinism is creeping in that can influence the way we think and act. ISCAST Fellow Denis Alexander explores how Christians can respond.

Originally published in The Melbourne Anglican.

ISCAST opinion articles invite writers to share their perspectives on various science–faith topics to generate a constructive conversation. While ISCAST is committed to orthodox Christian faith and mainstream science, our writers may come from a range of positions and do not represent ISCAST.

Asking whether we are slaves to our genes might sound melodramatic. Surely we left that kind of idea a long time ago? But it’s a good question for Christians to ask, partly because in its insidious new form genetic determinism can appear to threaten the freedom that we have in Christ.

It’s true that the bad old days of genetic determinism belonged to the earlier decades of the 20th century. From the 1880s to the 1940s it was widely believed that heredity determined race, class, mental health, and intelligence. Eugenic legislation ensured the compulsory sterilisation of hundreds of thousands of “physical and mental defectives” in the United States, Denmark, Sweden and Germany.

But we are now seeing a new kind of genetic determinism. Unlike the old, it’s absorbed more by a kind of cultural osmosis than by bold “scientific” assertions. Geneticists reporting their results tend to be cautious, highlighting the role of the environment. Despite this the language of genetic determinism has come into daily discourse. Phrases such as “It’s in her DNA” or “in this or that institution’s DNA” highlight characteristics that are supposedly permanent. The media often reports the discovery of what they call “a gene for” violence, or happiness, or monogamy.

A recent news report from the influential science journal Nature proclaimed that: “An increasing number of studies suggest that biology can exert a significant influence on political beliefs and behaviours … genes could exert a pull on attitudes concerning topics such as abortion, immigration, the death penalty and pacifism.” In such descriptions, genes are seen as something different from us ourselves, that exert a “pull”.

Rethinking Genetics

Part of the problem lies in exaggerated science reporting such as this. When the media reports the science accurately, then the support for genetic determinism fades away and we are left with a very different picture.

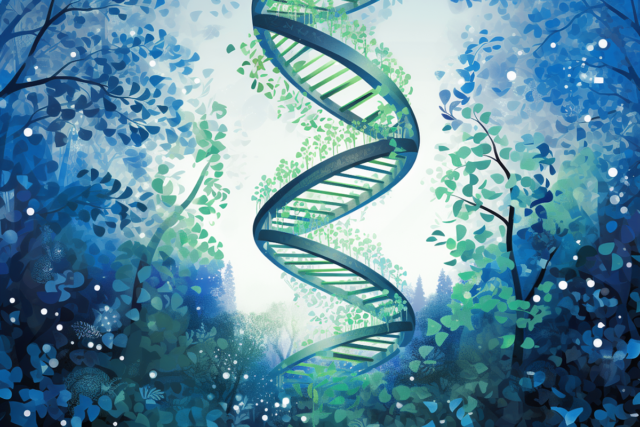

The key here is to think about the role of genes in human development. Yes, we wouldn’t be humans without the particular genomes—which are sets of DNA genetic information – that we all possess. But what is inherited from the parents is not naked DNA. By itself, DNA can do nothing. Instead egg and sperm fuse together to generate a complex system of molecules that cooperate to produce that lovely baby. Alone, DNA would be as useless as a piece of software without a computer to run it on. Biologically, human life begins as an integrated complex system and carries on that way to the end.

“Environments” are both internal and external. Inside our bodies every single cell is interacting with millions of other cells and every single organ with all the other organs. But as we continue to develop, our whole bodies are interacting with thousands of external environments. So our human identities and unique personalities are both 100 per cent genetic and 100 per cent environmental. Millions of factors integrated together during foetal development and in the postnatal years to generate the unique person, the unique “I”. The psalmist said that he was “knit together” in his mother’s womb, and we are all the products of this great knitting exercise.

Our human identities and unique personalities are both 100 per cent genetic and 100 per cent environmental.

Consider the human brain as an example of genes and environments being “knit together”. The human brain is the most complex entity in the known universe containing a staggering 500 trillion wiring connections, known as synapses. Amazingly most of the wiring in our brains develops during the first two years after birth. The infant brain is not a miniature version of the adult brain but a self-organising system that only self-assembles correctly if the right inputs are available at the right time. And that brain self-assembly requires thousands of inputs from the environment to proceed properly—light, sound, touch, pets, bugs, talking, plenty of parental love, and much else besides—all wonderfully combined together to produce a chirpy little cherub. Even in adulthood there is still a constant two-way flow of information going on between our genomes and the world around us. At the regulation level, our DNA is not quite the same after breakfast as it was before.

Do Different Genes Cause Different Behaviours?

We all have pretty much the same genes, otherwise we wouldn’t be fellow humans. But slight variations make big contributions to our human uniqueness. If you add up all our DNA variations then you find that all of us around the world differ in our genomes by around 0.5 to 1.0 per cent. Most of these variations make no difference to us at all, but some do.

“Behavioural genetics” is the research field that investigates whether and how those slight variations have any influence on our behaviours, often using identical twin studies. One aim of this research field is to calculate the “heritability” of different behavioural characteristics. In its technical sense, this refers to the proportion of the variance in a behavioural characteristic in a specified population that can be ascribed to genetic variation. It’s a population statistic about variability.

For example, “educational attainment” has a heritability in the range 40–60 per cent, but this doesn’t mean around half your ability to go to university is somehow determined by your genes. Instead, it means is that in the whole population of Melbourne, thousands of variant genes influence brain development in subtle ways during a long process of development in interaction with the environment. The end-result is that some people find academic attainment just that bit easier. But your free will remains intact. You can still choose to spend your life playing cricket, or making lots of money, or caring for the poor, and forget about going to university.

So variant genes can influence the differences in our behaviours—the likelihood that we do one thing more than another. If we are very tall, then it’s more likely that we’ll be good at playing basketball. But we need to distinguish carefully between things that “happen to us” with things that “we make happen”. We don’t choose our personalities—they “happen to us” during childhood as we develop, and our variant genes definitely influence that process. But as we grow up, we start to make things happen.

We need to distinguish carefully between things that “happen to us” with things that “we make happen”.

Humankind in the Image of God

In Genesis 1 humankind is created with dignity and worth, and called to play a delegated kingly role in caring for the created order, male and female alike. Each human individual is a unique person, loved by God. We now know that there is sufficient diversity in human DNA to guarantee the uniqueness of every person who has ever lived, or ever will live.

Being made in the image of God means that each human individual has a value and status that is not tied to their genetic endowment, social background, race, or any other factor. It also means that human beings are free to serve Him or not. We read in Joshua: “Choose for yourselves this day whom you will serve!”.

We can thank God for our wonderful human diversity. We can thank him also for our amazing genomes that make that diversity possible. We are not slaves to our genes, but free to serve God as we make our choices day by day.