Biotechnology has made remarkable advances in the last few decades. It has also raised ever-more-complex ethical questions. This is no more evident than in the recent announcement of the creation of “artificial embryos” (strictly, induced blastocyst-like structures,[1] or iBlastoids[2]).Announcements such as these tend to be praised as opening up unimagined vistas of bio-technical possibility, or damned as harbingers of an imagined biotechnological apocalypse.[3] Such polarisation into heroes and villains is all-too familiar in this social-media age, and tends to kill the possibility of meaningful discussion about questions relating to science and technology, the values inherent in them, and the role they ought to play in societies such as ours.

So, let me try to break the mould. I want to neither praise the good folk of Monash, nor bury them. Rather, I’d like to prompt us to ask questions, open up actual conversation about this technology and its possibilities and perils—and, indeed, a conversation about how we might engage in fruitful public discourse on thorny matters at the intersections of science, technology, society, ethics, and faith.[4]

For there are, indeed, thorny questions to negotiate here. For people such as Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, Anthony Fisher, the thickets are so barbed as to prohibit further exploration. Human life is sacred, and an intervention such as this that creates a facsimile of an early embryo, trespasses on territory that ought to be off-limit to us and our science. Others such as Julian Savulescu, see only virgin territory, the smooth uplands of scientific possibility and technological utility, and moral (or religious—perish the thought!) qualms such as this should not even be dignified with an answer.

Neither, it seems to me, fosters meaningful conversation.

Let me be clear: I am a Christian, and a Christian of a particular (conservative) kind—an evangelical and a Baptist (but please: for those who know the toxic mix of religion and politics that is America, both words mean something very different here). I value human life and see it as invested by God with inherent dignity and value (even as I know how vague and contested those terms can be). But I am also someone with medical training, who welcomes the contribution of medicine and biotechnology to the society in which I live, and values the scientific enterprise.

And it is precisely as such that I cannot adopt either the “boom” view of unfettered technical advance, nor the “doom” view of the evils of biotechnologies. For the Scriptures I seek to live by remind me of both the goodness of the world and the possibilities of human knowledge and culture, and the moral fallibility of human beings and the self-interest that so often drives our strivings. At times like this, that faith prompts me to ask a deceptively simple question: ‘for whom?’[5]

A question like that—asking, who gets to benefit? who pays the price? and who will control the kinds of questions that are asked and the ends and uses of the technologies that will be developed?—points out some of the thornier branches and may guide our thinking as we seek to navigate our way through these thickets.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. For, as I’ve noted, many of my fellow Christians would see insuperable problems with the very creation of iBlastoids.

So, what precisely are those concerns, and where do they come from? The principal concern lies in the nature of this thing. Many Christians believe that a human person’s life begins at conception, and so from the moment of conception this new being is invested with all the dignity and worth (and rights and privileges) of a human person. This means that anything that threatens the embryo’s life or well-being is inherently wrong, and acts that would end the embryo’s life (such as abortion) can be justified, if at all, in only the most exceptional of circumstances.[6] These views, so evident in debates about the ethics and legality of abortion (at times, abrasively, even offensively so), also come into play here. Or at least, they might.

However, things are a little tricky here. These blastocyst-like structures do not have all the features of a human blastocyst. Nor are they the product of conception—there is no fusion of egg and sperm to produce a new organism.[7]So what, then, are they? For those who hold to a “right to life” perspective, this is the crucial question.[8]

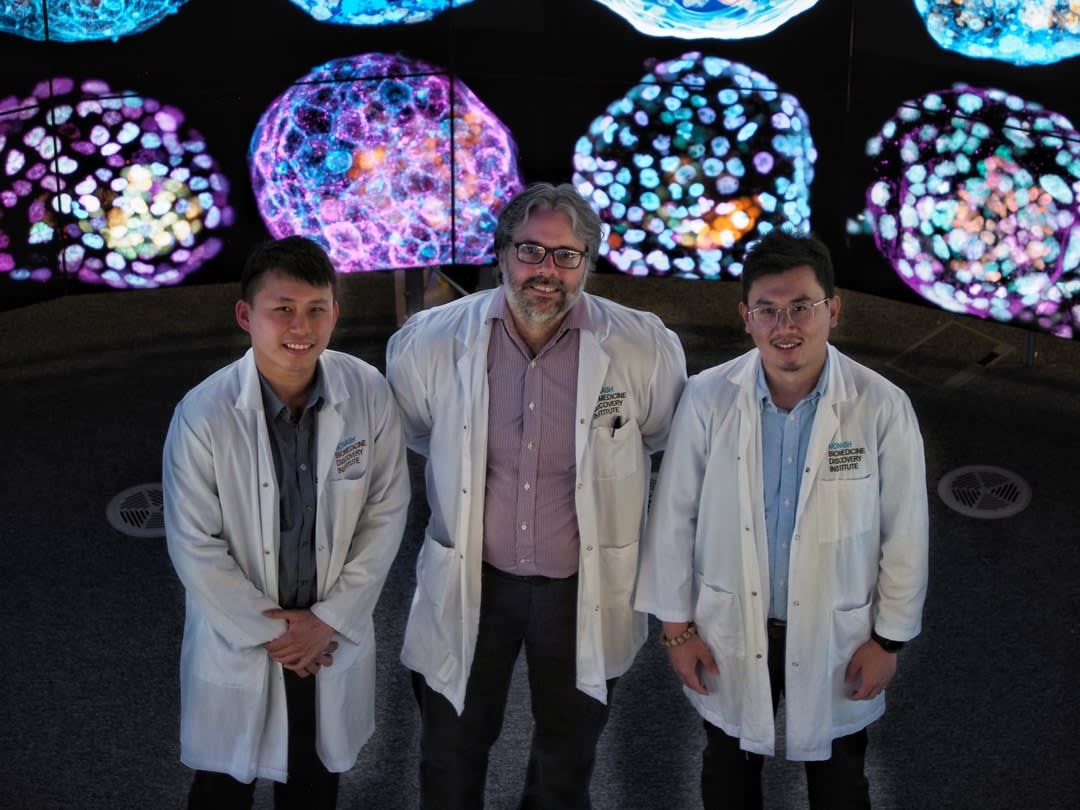

The researchers are clearly aware of this issue. The very terms they coined, Blastocyst-like structure, iBlastoid, seek to differentiate this entity from a normal human embryo. So too, the authors recognise the moral uncertainty here. Professor Jose Polo, the lead researcher of the Monash group, is quoted as saying: “How religious leaders will take this, I don’t know, to be honest. We need to remember this is a model. They don’t have development potential. They cannot make a baby.”[9] And that, they believe, makes all the difference. Despite the complex issues at stake, a human embryo is not being used in research, and so the ethical landscape is cleared.

For instance, Liu, et al, state: “As iBlastoids are generated from somatic cells, without destruction of a human embryo, we anticipate that this will facilitate the wider acceptance of iBlastoids as a model”.[10] They go on to say: “Given that iBlastoids with specific genetic loads can be generated, this will allow studies of early developmental diseases and screening for treatments, and as such has tremendous potential for understanding infertility and early pregnancy loss. iBlastoids could also serve as a platform for toxicity and viral susceptibility screens, as well as enabling gene therapy techniques.”[11]

But perhaps the thorns persist. A right-to-life advocate might suggest that this kind of research is morally unacceptable, precisely because the moral status of this entity is unclear. It is irresponsible, they might say, to create something that might or might not be human, for that would create, in turn, unacceptable ethical problems (should, or should it not be treated as a human person?). And it might even be worse than this: it might be that this is a Moreau-esque intermediary between human and non-human, transgressing a moral boundary by their very existence. It is more than a little ironic that research into adult stem cells has created this dilemma given the controversies surrounding the use of embryonic stem cells and the championing of adult stem cells as an ethically unproblematic alternative.

Now, it would be easy to dismiss these as the qualms of religious conservatives who seek to control society and limit the possibilities of technical advance. But that would be mistaken. For while they may be wrong—and I think they are—they pick up on basic questions that we ought to be able to discuss in a liberal democracy that seeks to understand what it is for our society to flourish and how to foster the good of all who live in it. Surely it matters to us who ought to be included in our moral community? Surely it matters to us whether our fellow humans have inherent value and, if so, what implications this has for us and our social policies? Surely it matters to us that those who might pay the price for any social or technical advance must be those who might also benefit from it? Simply rejecting—even lampooning them—as benighted, obstructionist, religious control freaks doesn’t further meaningful conversation.

But how, then, should we think about iBlastoids? As I’ve said, I don’t share a traditional “right-to-life” ethic on the status of the embryo. Texts such as Exodus 21:22-23, Psalm 51:5, Psalm 139:13, 16, and Luke 1:39-45 are often taken to prove that the human person comes into being at conception. I do not believe that sound exegesis justifies that claim. Nor do I believe that there are convincing philosophical or theological arguments for the view that human personal existence begins at conception. That is not the kind of value we ought to ascribe to the early human embryo. Their value lies in role they play in the normal story of a human life and our retrospective recognition of God’s scrutiny and care in all the stages of our life and its antecedents and development.

What we have here is a far cry from that. The cells that make up a blastocyst-like structure fit neither into the story of human procreation, nor as the beginning of the story of a new human life. The moral issues raised by some abortion practices do not pertain.

Other questions do. The researchers are clear that they see these entities as models for future research in human fertility and IVF. This, in turn, raises questions about IVF per se, and its social and human cost, equity of access, and the like. These matters are rarely raised at the social level—and even more rarely in IVF clinics. But perhaps the advent of the iBlastoid introduces the possibility of fruitful conversation on these underlying matters.

Similar questions can—and should—be raised about their use in the study of stem cells and their possible use in treatment or research. The possibility of using these structures for developing cell cultures for research into diseases and their treatment is tantalising. We need to ask hard questions about which kinds of diseases, and what kinds of therapy are researched, and who stands to benefit from them. Certainly, refining the technology as an avenue towards genetic manipulation of human embryos, even if for strictly “therapeutic” ends, raises thorny issues about the role of technology in shaping human futures (and future humans). Again, perhaps this research might prompt us to ask these questions.

These are just some of the questions we need to address as we think about this new biotechnology. But these aren’t just questions about the limits that ought to be placed on this technology. These are questions about what kind of community we ought to be, what kinds of futures we ought to imagine, and what role technology should play in that.

More than that. I dare to hope (and pray) that this new announcement might prompt us to quieten the shouts of praise or condemnation, and start having a meaningful conversation.

A shorter version of this article was published at Eternity News.

Image credit: UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL CENTER

[1] Yu, Leqian, Yulei Wei, Jialei Duan, Daniel A. Schmitz, Masahiro Sakurai, Lei Wang, Kunhua Wang, et al. “Blastocyst-Like Structures Generated from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells.” Nature (17 March 2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03356-y.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03356-y. A blastocyst is an early multi-cellular, pre-implantation phase of an embryo’s development.

[2] Liu, Xiaodong, Jia Ping Tan, Jan Schröder, Asma Aberkane, John F. Ouyang, Monika Mohenska, Sue Mei Lim, et al. “Modelling Human Blastocysts by Reprogramming Fibroblasts into Iblastoids.” Nature (17 March 2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03372-y. p.1.

[3] For the first, see https://www.smh.com.au/national/a-remarkable-chance-for-deeper-insight-into-one-of-humanity-s-greatest-mysteries-20210317-p57bkt.html, and Julian Savulescu’s characteristically pugnacious blog: https://blogs.bmj.com/medical-ethics/2021/03/18/ethics-iblastoids-and-brain-organoids-time-to-revise-antiquated-laws-and-processes/. For the second, see https://www.bioedge.org/bioethics/several-research-groups-create-artificial-embryos/13743, and Anthony Fisher’s opinion piece in The Catholic Weekly, 20/03/2021, “‘Artificial embryos’ first doesn’t cancel out fundamental human life questions”, https://www.catholicweekly.com.au/artificial-embryos-first-doesnt-cancel-out-fundamental-human-life-questions/.

[4] A similar line is taken by Munsie and Abud in their piece in The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/researchers-have-grown-human-embryos-from-skin-cells-what-does-that-mean-and-is-it-ethical-157228

[5] With thanks to my friend and colleague Gordon Preece.

[6] See Wilger, Kevin. “Gaps in Embryo Model Ethics.” Ethics & Medics 45, no. 10 (2020): 1-4.

[7] This is clear in both Yu, et al., and Liu, et al.

[8] Wilger, 2–4, explores this from a traditional Catholic perspective.

[9] https://www.smh.com.au/national/scientists-create-model-embryos-in-lab-raising-major-ethical-questions-20210317-p57bkc.html

[10] Liu, et al, 5.

[11] Liu, et al, 6; Yu, et al, 6.