D. Gareth Jones

Biography

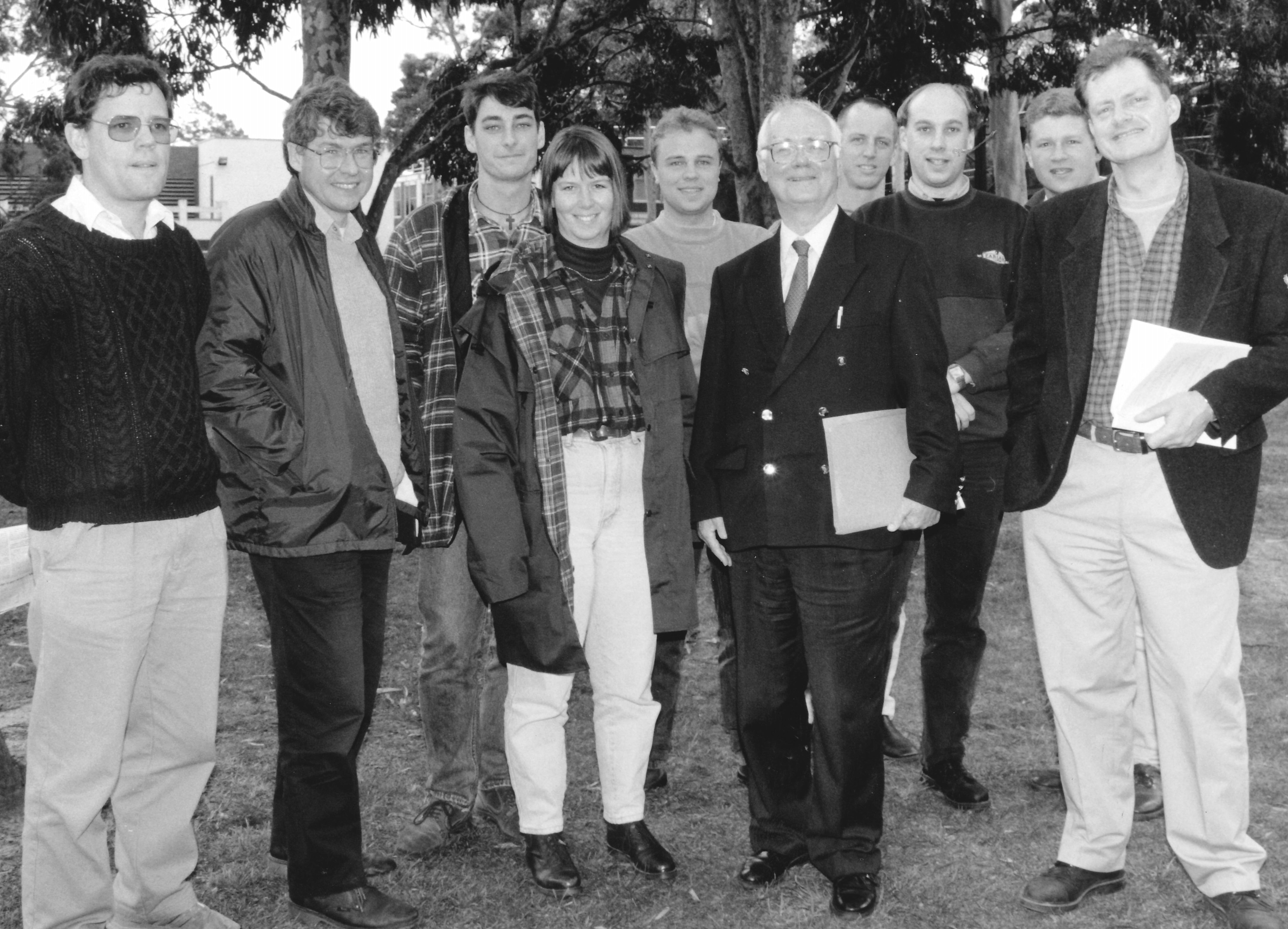

Gareth Jones is Emeritus Professor in the Department of Anatomy at the University of Otago, New Zealand. For many years he was Head of the Anatomy Department, following which he was Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic and International). Subsequently, he was Director of the Bioethics Centre at Otago. Prior to his time in Otago he held positions in the University of Western Australia, and University College London.

In 2004 he was made a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (CNZM) for his contributions to science and education. He holds the degrees of DSc and MD, for his publications in neuroscience and bioethics respectively. For a number of years, he served on the New Zealand Government’s Advisory Committee on Assisted Reproductive Technology.

His current research interests span a number of areas of bioethics, approached from the perspective of a biomedical scientist, with particular interests in embryology and neuroscience. All his bioethical writings are informed by his science, especially as they relate to the dead human body, and the uses to which human tissue and human material may be put in teaching and research. Core issues include the moral status of the embryo, pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), policy issues surrounding research using human embryos and embryonic stem cells, notions of biomedical enhancement, and the interplay of genetic and environmental factors in ethical assessment.

Interests in the science-religion field overlap these bioethical interests. As a result, he speaks and writes in these areas, both from a specific Christian perspective and as an academic/policy commentator. His books include Speaking for the Dead: The Human Body in Biology and Medicine; Designers of the Future: Who Should Make the Decisions? and The Peril and Promise of Medical Technology.

Background

The title of this chapter aims to be provocative, by putting together the words, ‘privilege’ and ‘secular’, since this presupposes that one is working in an environment surrounded by those with different beliefs and outlooks from one’s own. My argument is that by displaying Christian virtues in the workplace we demonstrate fundamental Christian truths, evident to those who under other circumstances would pay limited, if any, attention to Christian claims.

As an academic, I have had a wide variety of experiences, from being a long-time Head of Department and then Deputy Vice-Chancellor, to being director of the Bioethics Centre. Over these years I have attempted to function as a Christian and have tried to be aware of my responsibilities and privileges as a Christian. My working life commenced as a young Christian in a large department that was avowedly atheistic/agnostic, at a time when science was in the ascendancy with no place for anything remotely Christian. As time went on, I became increasingly convinced that academic life with an emphasis on research, teaching, and creative thinking was a privileged one, and the one to which I had been called as a Christian. I also came to realize that I am a leader who is capable of undertaking a diverse set of administrative responsibilities.

It is unfortunate that what Christians do and how they function in their workplaces appear very often to be of little direct interest to their churches. For them the world outside their doors is foreign territory, even though this is where Christians and everyone else spend the bulk of their lives. For me this is akin to heresy, since it marks a serious departure from much traditional Christian thinking in which work is regarded as a vocation or calling. According to this notion, Christians are called into specific jobs, whether at home or in society, whether professional or manual, and it is in these domains that they are to live out their calling. All valid work is of equal value in God’s sight. While this does not define what constitutes ‘valid’ work, it highlights the fact that Christians are to be faithful to God wherever he leads: in forensic psychology, evolutionary ecology, doing voluntary work in the community, or bringing up children at home. God’s calling takes seriously our abilities and expertise, since they come from him as a manifestation of his sovereign activity in his creation.

Establishing the ground work

My starting point is provided by principles provided by the biblical writers. The first hint comes from Paul in writing to the church at Ephesus, where he outlined how the new life in Christ was to work out in practical terms (Ephesians chapters 4-6). He was speaking to Christians, most of whom would have been slaves who had to work under their masters. Difficult as this relationship would frequently have been, they were not to lie, get angry or be bitter, but were to earn an honest living, being kind and helpful to others, and also forgiving one another. More specifically, they were to submit themselves to one another because of their reverence for Christ (Ephesians 5:21). They were to treat everyone with whom they came into contact with consideration and empathy.

Against this background, Paul throws the spotlight onto three sets of relationships, one of which was that of slaves to masters. This was where most of those in the early church found themselves, since in the Roman Empire slaves constituted the work force, and represented the typical workplace situation. It is, therefore, quite apposite to take this teaching as a guide to workplace relationships within contemporary society different though they are in so many ways. If we think we are hard done by, it is unlikely to be as difficult as that which Christian slaves in the first century had to endure.

The first underlying principle was that of obedience (Ephesians 6: 5), rather than rebellion. They were to function effectively as Christians within a diabolical system. They were to fulfil their obligations within the system of slavery even though this would not have been their choice, and were to do this ‘with fear and trembling’. Slaves were to carry out their appointed tasks with the same attitude and the same determination as characterized Paul in his proclamation of the gospel. This parallel is revolutionary, transforming the experiences of the Christian slaves who were to give this work undivided attention, in spite of their status as slaves (Ephesians 6: 6-7).

The second underlying principle is that slaves were to work ‘as to the Lord’. This is because a Christ-centred frame of reference transforms everything for Christians. As slaves obeyed their earthly masters, they were serving Christ, and were doing the will of God (Ephesians 6: 5, 6). They were to work cheerfully because they were serving Christ through the service of their masters on earth (6: 7). In following Christ, they became free, as their new life in Christ changed their human bondage out of all recognition. No longer were they constrained by harshness and possibly injustice. In being liberated from the constraints of trying to please those around them, they began to experience the freedom that Christ alone can bring. They were free in Christ, even though to human eyes they were in shackles.

The third principle is that, because they were working for Christ, they knew they would be rewarded by him for their good work in the ordinariness of day-by-day existence (Ephesians 6: 8). Their ordinary jobs and the manner in which they performed them could be seen as integral to what they were as Christians.

A Christian way for employees

First, unlike slaves, we generally have choices about what we do, even though in practice the choices may be limited. An element of choice, however, is a privilege.

Second, the calibre of Christian witness is demonstrated by the manner in which they function in the work situation: whether in teaching, doing research, dealing with customers, working for exams or preparing assignments. The most brilliant evangelist in the office is seriously hampered, indeed is eviscerated, if their work is shoddy and unreliable.

Third, Christians witness to what they are through the way in which they work, and not in spite of it. Their integrity with regard to small things is crucial to their testimony over large matters. Giving value each day to their employer or clients is the basis of their testimony to Christ as Lord of their lives. If engaged in scientific research, the integrity of that work and its reproducibility is fundamental to their standing as people of faith, as is the way in which they treat students and fellow researchers.

Fourth, since Christians are not simply to work well when someone is checking up on them, they are placed in an immensely liberating position. They do not work in order to climb the corporate ladder, or to compete with others for the top position; they do it in order to serve Christ. They are freed even in uninspiring work situations as when all their experiments may be coming to naught. In an environment where all that seems to matter is obtaining lucrative grants and publishing in high impact journals, they inject into this environment a higher calling; that of being Christ’s people in and through everything they do, especially when they are very successful by the usual measures of academia.

Fifth, Christians will not always be the most able, but they are to maximize whatever abilities they have. They are to be industrious, honest, truthful, reliable, helpful and trustworthy. They are to be good research assistants, lecturers, research directors, professors; they are to excel to the utmost of their capabilities, because this is the way in which God is honoured.

Sixth, they also have the privilege of knowing that as they study neuroscience, ancient history, laser physics, or tutor undergraduate students, they are doing work that is important within a Christian context. If these are the areas where they have expertise and abilities, and if they have not been called into any other realm, these are the areas to which they have been called and where they are to be content. Christ is Lord of all, even of the mundane and the challenging.

On being a master

A striking feature of the master—slave equation is the parallel between the two sides (compare Ephesians 6: 9, with 5 – 8). There is no hint that masters are superior to slaves, even though their position within society is different. The underlying principle is that masters are to act in the same way towards their slaves as slaves have already been instructed to act towards their masters. If masters expect to receive respect from their slaves, they are to respect their slaves; if they expect their slaves to work well for them, they in turn are to treat their slaves with respect and courtesy. There is to be no hint of privileged superiority in the lifestyle of masters. The revolutionary nature of this teaching is as compelling today as it was in Paul’s day. Regardless of the positions we may occupy within a workplace, respect for one another is foundational. When this is lacking, bitterness, envy and petty political wrangles can mar even the most promising of situations.

Christian masters are to act just as slaves are to act: with ‘fear and trembling’, ‘in singleness of heart’, and ‘as unto Christ’, because they too are Christ’s servants and are to do his will at all times. Christian leaders and employers are to serve the Lord, just as much as Christian employees are to serve the Lord. There is no difference. Since Christians are all one in Christ, any hint of a hierarchy of importance disappears, regardless of position within an organization.

In view of this, Paul’s next point should be self-evident: masters are not to threaten their slaves. Just as slaves are not to work only when their masters are looking, so masters are not to misuse their position of authority by issuing threats of punishment. For Christian masters, threatening slaves had become untenable. There was to be no imbalance in power relationships. Christian masters were never deliberately to keep slaves down, or exercise power with subtle insinuations and veiled threats. And so, when Paul wrote to the Christian master, Philemon, about his runaway slave Onesimus, he reminded Philemon that whatever had happened in the past, his present obligation was to treat him as a brother (Philemon 16). Philemon’s supreme obligation was to serve Christ, and not himself.

It is a short distance from Philemon to the responsibility of Christian leaders towards their employees, namely, if necessary, to put Christ above the organization. When there are financial problems within an organization and staff have to be made redundant, this is to be carried out in such a way that staff retain their dignity. Those who are potentially superfluous to an organization and those of great importance to it, are of equal significance and dignity in the eyes of God. This must be mirrored in employment policies.

All are accountable to the Lord, and in a very profound way we are to make ourselves accountable to each other; even the master to the slave, the employer to the employee, the leader within an organization to the most junior within that same organization. If the person with authority is acting fairly, he/she has nothing to hide; there should be an openness and accountability in that organization because all are working for the same ends, which is the good of the organization and which in turn should be the good of the employees.

Leaders, like employees, have to function within very mixed workplaces, where injustice, poor decision-making, indecision, and petty rivalries and jealousies occur. If they are serving Christ, they will do their best for their workplace, they will enhance conditions as much as feasible, and will constantly endeavour to improve the lot of the workers in whatever ways are open to them. Inevitably, there will be limits to what can be done, sometimes very severe limits. Whatever the case, Christian leaders are to act honourably, with the utmost integrity and foresight, with the good of the firm and employees (or the laboratory and researchers) uppermost, and with an openness that refuses to hide important issues from employees.

Acting as prophet and servant

Two thrusts of biblical teaching are crucial and need to be held in tension: being prophet and servant, the balance between acting like one of the minor prophets, and as a servant like Christ. As Amos, the prophet, looked at God’s own people, he saw an enormous amount of social injustice (Amos 8: 4-14). Although they were religious, they oppressed those unable to fend for themselves, notably the destitute and the weak, and they found certain religious strictures limiting because they interfered with making money. They were unscrupulous and dishonest in financial matters, giving short measures and tilting the scales fraudulently (Amos 8: 5). They sold the leftovers, and used paltry debts, such as a pair of shoes, as justification for selling a person into slavery (Amos 8: 5, 6).

Not only did Amos condemn the people, he also spelled out God’s judgement (Amos 8: 7-14). From this we learn that we are never to ignore instances of injustice. To turn a blind eye to injustice is to condone the wrong and fail to stand up for the downtrodden and disadvantaged. The prophets were deeply concerned for the good of society, and recognized that impoverished moral standards were society’s downfall and would eventually lead to its destruction.

In contemporary workplaces we are to be prepared to critique the system in which we find ourselves, rather than the people behind that system, although this can be difficult. Nevertheless, an attempt has to be made to make and retain this distinction, because only when this is done does it become possible to carry out a rigorous critique of what is wrong, without being unduly judgemental.

It is the good of the workplace, whether it be a laboratory, business concern, shop, school, university, or hospital board, that should shine through. Our goal is to assist our institution or laboratory; to bring it back to a more moral foundation, where the welfare of all will be enhanced, and where all within it will be encouraged to give of their best. It is never to provide ourselves with a power base for self-centred ambitions.

Inevitably, though, questioning policy decisions, especially when they have been arrived at with little open discussion, is threatening to those who wish to avoid open debate. The goal is to lead colleagues away from injustice, and towards integrity and honesty in their business dealings and treatment of people. We may not be thanked for acting in these ways, but this is not a reason to shun the role of prophet when such a role appears to be necessary, criticizing the system where criticism is called for, and seeking a better way when this is desperately needed.

Important as is the prophetic element, it is to be complemented by the element of servanthood, namely, our attitude of concern and service toward those with whom we have dealings each day, the people for whom we may have direct responsibility, and also those responsible for any unjust or undesirable practices that affect us. We never fight injustice with anger and force, since that leads to further injustice. To condemn others, and to indulge in a character assassination of them, entail bitterness and anger within our own lives, bitterness and anger that will eventually destroy us as positive, faithful followers of Jesus Christ.

By contrast, a Christian response is a totally different one, one that was portrayed in various ways by Jesus with his emphasis upon servanthood. In Luke 14, Jesus painted the picture of guests at a wedding feast, who rushed in to get the best places. For Jesus this was the complete opposite of his priorities; the guests were first to consider the needs and welfare of the other guests, by ensuring that others had the best places (Luke 14: 10). This was the essence of acting humbly and of serving others. And when they themselves put on a special meal, they were not to invite their friends or rich neighbours, but the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind – those who were not in a position to reciprocate (Luke 14: 12-14). They were to act selflessly, doing good to those unable to repay them, and serving others expecting nothing in return.

This emphasis on humility, acceptance of the unlovely, and forgiveness of one’s enemies entails doing good to those who do not do good to us, and acting justly to those whose actions are unjust. It entails praying that the unjust will be changed, and praying that God will deal with those who are misusing us and treating us unfairly (Matthew 5: 44). And it will lead to prayer for ourselves that we will be able to respond openly and honestly in situations where we know there is opposition and a lack of openness and honesty.

Those in senior positions are to be concerned for the welfare of juniors, since these are the people for whom they have direct responsibility. They are to be concerned for their welfare and their good, since the most junior technician, lab assistant, or student is worth as much as they are. Those for whom they have responsibility are to be given opportunities to develop and fulfil themselves, and to advance within the research unit, administration, or university.

The contrast between secular and Christian perspectives was clearly expressed by Jesus himself, when he indicated how different their perspectives were to be from those of the ‘rulers of the gentiles’ (Mark 10: 42-44). For Christians, the challenge is to reinterpret secular expectations by functioning as servants to those “below” them. Such responses are only possible as Christians come to accept God’s sovereignty and overriding goodness, knowing that his purposes will ultimately be fulfilled and that these include purposes for them in the situation where they find themselves. Obedience to God leads to an acceptance of the “now”, even while Christians act to transform the “now” in their prophetic role. It is as the roles of prophet and servant are merged, that Christians can become an oasis of justice and forgiveness in the midst of a desert of injustice and lack of forgiveness.

Living out one’s faith in a pluralistic world

The way in which we function in the workplace is crucial to the character of the message we give those with whom we come into contact. To varying degrees we act both as masters and slaves, simultaneously or more frequently, at different times. On occasion we are in control of others; at other times we are subject to the control of others.

The values at the core of a Christian lifestyle are driven by humility as shown supremely by a willingness to learn from others. The counter cultural nature of this approach becomes clear when it is realized that a repercussion is that we make ourselves vulnerable to criticism, alternative and challenging ideas, a questioning of our motives and goals, and even the injustice of those in authority. As soon as we treat others as beings on the same level as ourselves, we invite their contributions. We ask them to provide ideas and thoughts, and perhaps the ones they come up with will be at variance with our own. In other words, rather than protecting ourselves from the onslaught of others, we expose ourselves as we invite comments and contributions.

Vulnerability is basic to Christian attitudes. Christ could have shielded himself from the questioning and probing of the sceptics of his day, and yet he invited their comments and questions. He debated with the Pharisees and Sadducees; he turned their trick questions to his own advantage, and he elicited supremely important teaching from scurrilously ambivalent queries. In debating in this way, Jesus made himself vulnerable, since he exposed his teaching and his message about who he was to the scrutiny of some of the most ardent exponents of an alternative tradition. What emerged out of the tumult of dialogue was a clear picture of who Jesus was, and of the way to the kingdom of God. Making oneself vulnerable requires a deep commitment to people and their welfare. But there is no option for Christians who wish to lead and work with others rather than in spite of them.

Acting in this manner holds out the hope of acting as peacemakers in very secular, diverse workplaces. All problems will not be resolved, and we may not escape controversy ourselves, and yet a hallmark of the Christian way is that of peace, shalom. Workplaces should be better places for the presence of Christians; when this is not the case, the question must be asked whether the Christians have failed. Those who are functioning as Christ’s ambassadors, should be stamping the way of Jesus on their workplaces, even in very small corners of them.

An allied characteristic is that of openness to the contributions and insights of others. This will not happen if we dictate everything, and if we expect our every thought to be accepted as holy writ. Autocrats are not open, because they see no need for it; they have all the answers, and no further contributions are needed. This is not the way of Christ. The problem with autocrats is that they feel threatened by those who may have more ideas than them or may be able to challenge them. They protect themselves by shutting others out; by refusing to be open. Christians who feel like this are to learn to trust in God who will protect them, however much they fear the abilities of those around them. If God has called them to their position, he will equip them for the tasks he has given them.

If one starts from the premise that all are equal in the sight of God, the next step is to realize that everyone within an organization has the potential to contribute in some way to the functioning and directions of the organization. For instance, asking junior members of a laboratory to provide feedback (which they know will be taken seriously) is the surest way of enhancing their image of themselves as people of worth and dignity. This is implicit within any Christian perspective. Acting like this will also lead to the creation of an atmosphere of trust and respect, because as far as feasible all are being taken seriously. Openness also leads to good communication. The essence of a successful leader at any level is meeting people face-to-face and not by email. It is only in this way that we get to know others as real human beings. They become something more than mere employees; they become people who are important to God and to the organization of which they are a part.

But what is possible in the real world?

These notions can appear idealistic in the extreme, essentially stillborn, as soon as they come into contact with the grubby real world of cut-throat ambition, shady dealings, immense egos and out-of-control ambitions. Academic life in particular frequently manifests characteristics of this ilk. No wonder Christians, aiming to demonstrate the fruit of the Spirit (Galatians 5: 22-23) can feel intimidated. The two worlds appear incommensurate. Vulnerability, openness, transparency and honesty against self-centredness, aggression, and deviousness. The competing forces appear ill-matched. And yet, the Christian way is always counter-cultural, and the essence of faith is to trust in God and in his goodness and faithfulness. He will look after his people as they follow him and abide by his promises. They are never left alone to battle on unaided, especially when they have been called to be his witnesses and servants on the front line, in the everyday world, utilizing the wisdom, expertise and experience they have been given.