John Pilbrow

Biographical

John Pilbrow, who was born and brought up in New Zealand, has been involved at the faith-science interface for more than six decades. In this account he identifies a number of influences from his childhood and adolescence that stimulated his interest in science and that laid a foundation for his later Christian commitment.

His first encounter with science occurred towards the end of WWII as a seven-year-old, through his family’s participation in a NZ DSIR[i] research project concerned with the edibility of dried fruit and vegetables for NZ troops serving overseas. He still recalls helping to fill out report sheets. The next important events were school excursions to a dried milk factory and an agricultural college.

From 1948-1961 he lived in Christchurch, and was educated at Christchurch Boys’ High School and the University of Canterbury[ii] where he graduated BSc (Hons) and MSc both with first class honours in Physics. He then gained his DPhil in Physics at Oxford and later a Monash DSc.

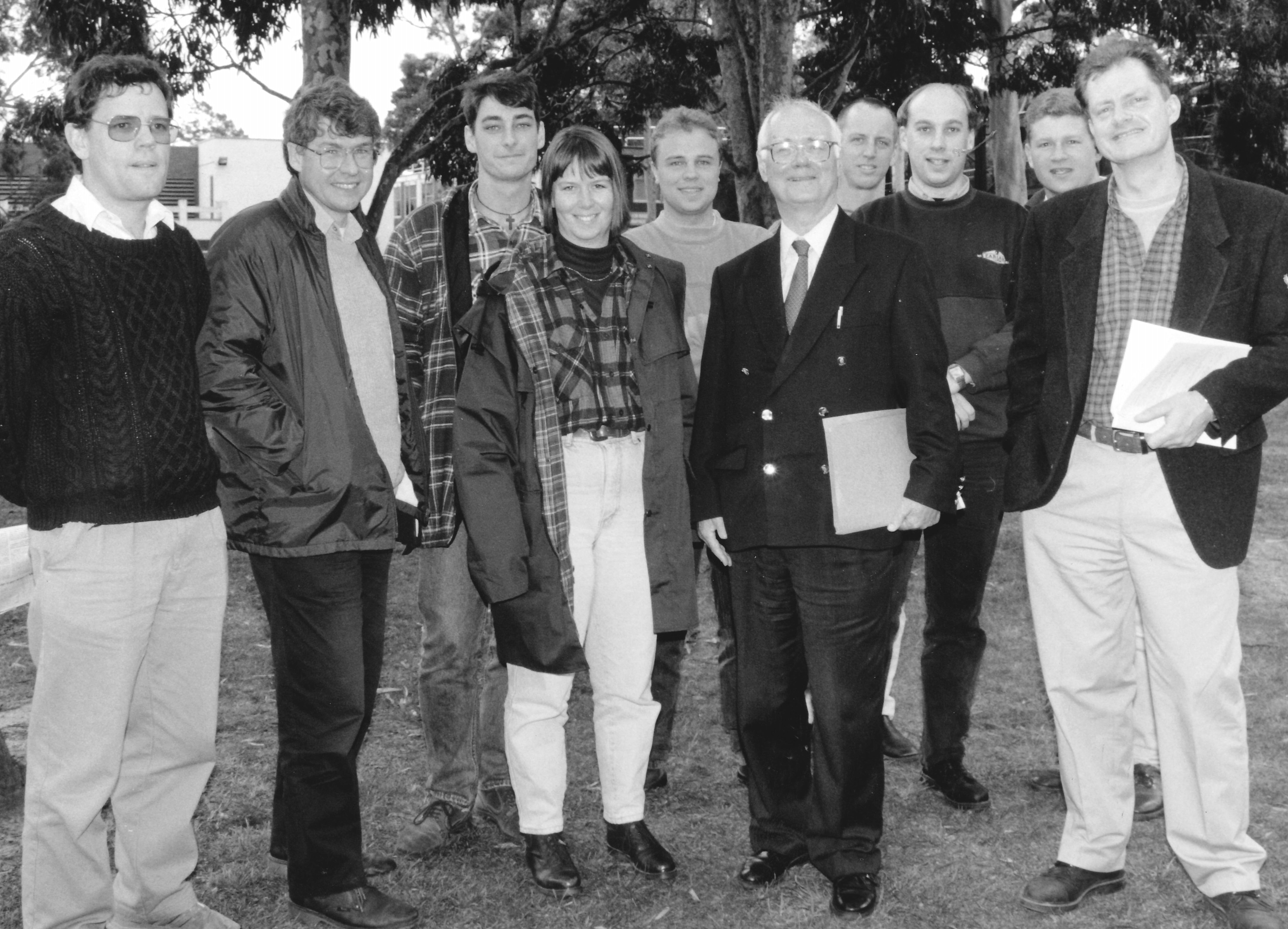

Appointed Lecturer in Physics at Monash in 1965, John progressed through several promotions, ultimately to a Personal Chair, and was Head of Department for nine years. He also served as President of the Australian Institute of Physics (AIP) and the International EPR/ESR[iii] Society. He was awarded the 1998 Bruker Prize for EPR Spectroscopy and presented the Bruker Lecture for that year in the UK.

Appointed Emeritus Professor of Physics upon retirement, John has continued his active engagement at the faith-science interface, e.g. serving as ISCAST President from 2006-9 and writing articles and book reviews for The Melbourne Anglican.

No place to hide

As a Christian, I sought to fulfil my commitment to Christ in the whole of my life, including my professional and academic life. It’s been an interesting and challenging journey, with much to be thankful for. And as I spent my entire career in one place, I realised that others had ample opportunity to assess whether my faith and integrity were genuine. There was nowhere to hide!

It is a tall order to reflect on those familiar words from the Lord’s Prayer, ‘your kingdom come, your will be done on earth as it is in heaven.‘ This two-fold petition implies that there is a connection between seeking to fulfil the will of God and the coming of God’s kingdom. In the New Testament Jesus makes it clear that there is both a now and not yet aspect. Thus, how we live now, and how we have lived, are of paramount importance.

This account cannot be disconnected from my childhood and adolescence. There were many formative influences in those early years; some relating to Christian faith and others that pointed me towards a future in science, particularly school excursions to the nearby Glaxo Dried Milk Factory and to Massey Agricultural College (now Massey University). People in white lab coats and shelves full of coloured chemicals left a lasting impression. In parallel, I look back with gratitude for the monthly Anglican Family Service and weekly Sunday School in our local rural community.

A little later, my supposed ‘idyllic’ rural world was turned upside down when my parents made a sacrificial decision to move to Christchurch to take care of my Grandmother. As it turned out this opened up new opportunities in all sorts of ways, culminating 13 years later in marriage and heading to Oxford to undertake doctoral studies in Physics.

In Christchurch, first of all I attended the local Primary School, situated by a picturesque tree-lined river, where I settled in quickly and made many new friends. I soon discovered the Christchurch Municipal Library which became a favourite haunt where many happy hours were spent over the years. Our family joined the local Anglican Church and I soon found myself in the Church Choir, singing at both morning and evening services. I remain grateful for the discipline of learning a new anthem each week and for this introduction to good Church Music. I later rejoined the Choir as an adult.

Moving on to Boys’ High School for five years, I discovered an aptitude for Mathematics and Science, especially Physics. The Senior Chemistry Teacher, who encouraged us to aim high and to start thinking about a career in science, emphasised that we’d need to do PhDs! Just after my 14th birthday he asked me where I planned to do my PhD! By this time I was firmly heading for a career in science. Laboratories were managed by ‘Lab Boys’, under the supervision of a Senior Science Teacher, and for three years I was a Physics ‘Lab Boy’. We were responsible for setting out equipment and, of course, putting it all away! While this arrangement would run foul of today’s OHS requirements, it was the training ground for many successful academics and researchers, including one contemporary who became a Fellow of the Royal Society[iv].

School Assembly every day involved a Hymn, a Bible Reading and Prayers (including the Lord’s Prayer)! And this in a State High School! The Senior Music Master, also a Church Organist and Choirmaster, ensured that the School Choir repertoire always included Christian anthems!

I also became a keen member of the Sixth Form Maths Society run by W.W. Sawyer[v], from Canterbury University. Membership was open to Sixth Form Students from amongst all Canterbury secondary schools. At two meetings each year, selected students presented solutions to problems previously circulated by Sawyer. My first ever ‘academic’ lecture was an exposition of the symmetry properties of the icosohedron[vi], complete with a model, which alerted me to the power of symmetry principles important later in my research in magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

I then spent five years at The University of Canterbury specialising in Physics and Mathematics, before gaining a Scholarship to study for my DPhil at Oxford. Extra curricular activities included: Two years as Hon. Secretary of the Athletics Club, during which time I rewrote its Constitution; Membership of the University’s Orientation Committee; and with my future wife, Susan, Membership of the Evangelical Union Committee.

My first experience of real scientific research, as distinct from undergraduate lab experiments, occurred over the Summer Vacation at the end of my second undergraduate year as a Vacation Scholar in the NZ DSIR Geothermal Division. My work on modifying a flow meter designed for measuring superheated water flow rates deep underground resulted in a single author paper published during my honours year. The following summer I built some electronic equipment for the University of Canterbury Upper Atmospheric Research Group, gaining skills that were immensely beneficial early during my career in magnetic resonance.

During my third year, I enrolled in Philosophy of Science on top of a full load in Physics and Advanced Mathematics, but soon realised that I was overloaded. I gave up the course but not the issues as I had read all of the prescribed texts during the summer vacation. This supplemented what I had previously gleaned as an avid reader of the biographies of great scientists from about the age of 13. Training for middle distance running also impacted on time for study!

When embarking on my MSc, having decided against Upper Atmospheric Physics, I was given 30 seconds to decide between Optical Spectroscopy and Electron Paramagnetic Resonance! I chose the latter and EPR Spectroscopy became the dominant technique I used for the rest of my career in Solid State Physics and with collaborators, addressing problems in inorganic chemistry and biochemistry.

While I look back with gratitude for the influences throughout my childhood and adolescence during which I had learned a good deal about Christianity, I had not grasped that at its heart was a personal relationship with Christ. It was during my third undergraduate year that things began to fall into place. A keen runner, I usually went for a lunchtime run most days. However, an injury meant that I was unable to do so for several weeks and, at this time, I became aware that there were to be five lunchtime lectures and a Saturday evening talk as part of a ‘low-key’ Mission sponsored by the Evangelical Union. The talks by visiting Irish Missionary Dr Alan Cole proved to be for me a catalyst. Late on the Saturday night, in my own room, I experienced a momentary sense of the presence of Christ[vii] and, strange as it may seem, at that moment I realised that I actually believed! Kneeling by my bed, there and then I committed my life to Jesus, a commitment that has endured for more 62 years. The following afternoon I felt drawn to the student Bible Class at the local Parish, which I continued to attend for more than two years until completing my MSc. The Vicar, who was very widely read and a voracious reader, strongly encouraged me to read widely, advice that I have continued to follow!

Familiar texts that I had learned along the way suddenly became richer and fuller. For example, Gen 1:26

“..God created humankind in his image…” (NRSV)

This had a profound impact on my understanding of myself as a bearer of the Image of God. The implication was that everyone deserved respect, something that underpinned my relationships with colleagues and students throughout my academic career. Then there was Gen 1:28, concerning stewardship of God’s creation.

“God blessed them, and God said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth’” (NRSV)

As I was approaching a decision regarding my future, I wondered whether science could be a Christian vocation. These texts from the Epistle to the Colossians got me started: –

Col 3:17, “And whatever you do, whether in word or deed, do it all in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him.” Col 3:23-24, “Whatever your task, put yourselves into it, as done for the Lord and not for your masters, since you know from the Lord you will receive the inheritance as your reward; you serve the Lord Christ.” Col 4:5, “Conduct yourselves wisely toward outsiders, making the most of the time”.[NRSV]

Of course, there is more to a full theological understanding of science as a Christian Vocation than provided by these texts. For example, I refer readers to two key paragraphs (reproduced in an endnote) from a BBC Sermon by former Astrophysicist and Theologian Professor David Wilkinson[viii]. I could only wish such a statement had been available back in 1959!

My life has involved many unexpected surprises. The Chairman of Scripture Union (SU) in New Zealand asked what I planned to during the several months between completing my MSc and going to Oxford. So I accepted an invitation to join the NZ SU Staff for about six months to support the 40 or so Crusader Groups in Secondary Schools in the South Island. As I look back on those six months, during which time I stayed with many fine Christian people, I was privileged to observe how they lived out their Christian faithfulness in their lives and work.

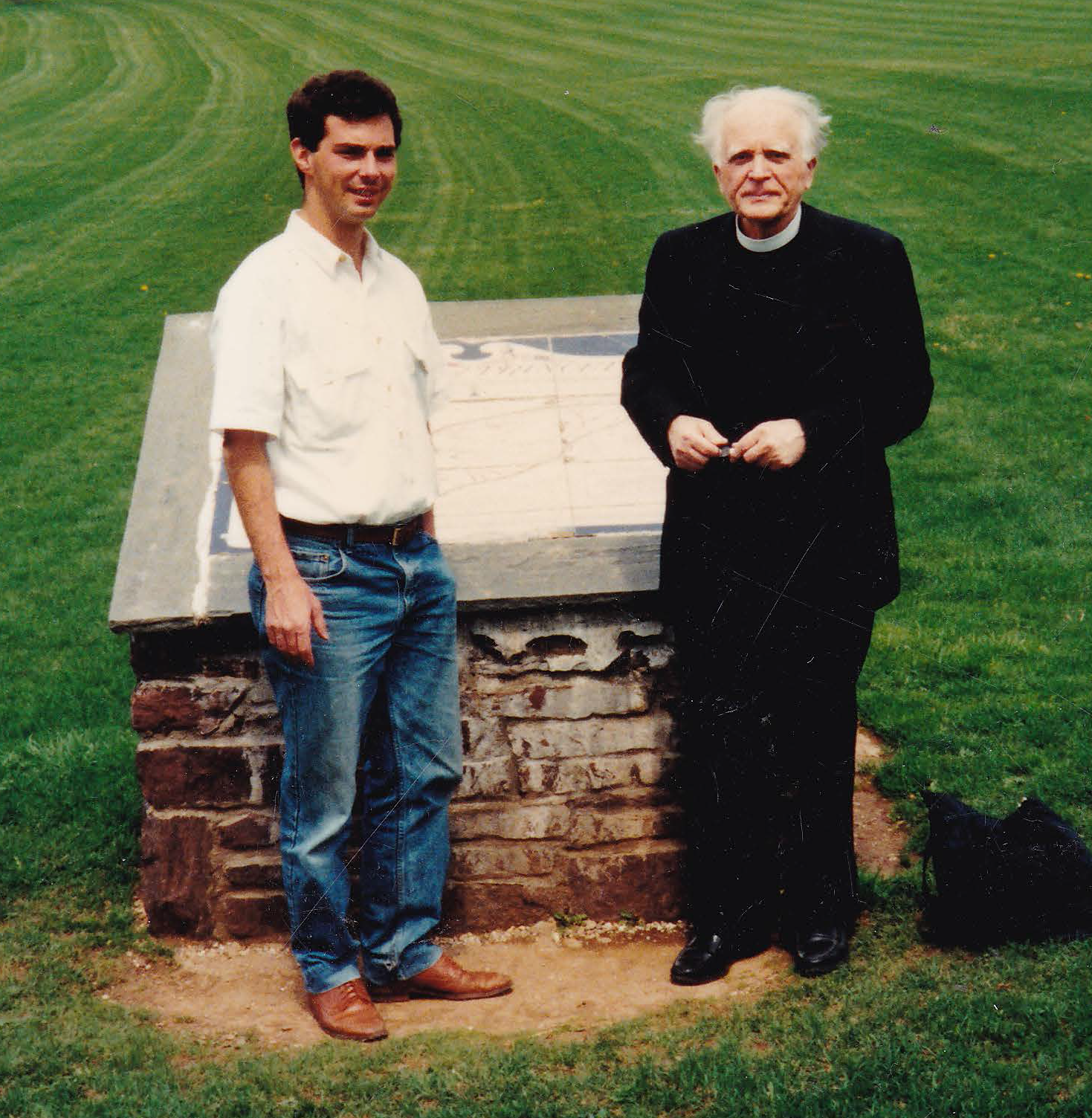

On moving to the bigger world of Oxford University to study for my DPhil in Physics, an unexpected bonus was the discovery that of the five doctoral students in our Lab, three of us were Christians. One of the others became a Christian a few years later. Many opportunities for new friendships, Christian Fellowship and fruitful discussions were available ‘on-tap’ as it were. I was soon introduced to the Oxford Research Scientists’ Christian Fellowship (RSCF), which met in the rooms of our former ISCAST President John White, then a Junior Research Fellow at Lincoln College. Another member was a young senior academic, John Houghton[ix] (later Sir John), and Lead Author of the first three Reports of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

It was an enriching experience being in an environment where one could attend two or three specialist seminars each week and the weekly Colloquium! One particular Colloquium stands out for it raised important questions for the Christians amongst us. The talk by Professor Herman Bondi from London University on Steady State Cosmology[x] indicated a hidden agenda viz. a theory that did not allow for a Creator. However, the discovery of the Microwave Background Radiation from the early universe in 1964 adjudicated in favour of Big Bang Cosmology, and so Steady State Cosmology was relegated to a footnote in the history of cosmology!

When my time in Oxford was coming to a close, and as my father had been battling cancer for many years, I turned down an excellent post-doctoral opportunity in the USA. Instead I accepted an appointment as Lecturer in Physics at Monash University, so as to be nearer our families in NZ. In fact I remained in the Monash Physics Department for 36 years and then continued doing research part-time for a further 10 years. Monash turned out to be a good place to do research. There was an infectious vibrancy about the place, a large cohort of able graduate students and lively discussion in the Physics Common Room at morning and afternoon teatimes and at lunchtime. I soon joined the small Melbourne RSCF Group which ran for about 15 more years. My involvement with ISCAST began in 1991.

I felt it to be an enormous privilege to be an academic scientist and I found the mix of teaching and research suited me. And of course, I accepted my share of responsibility in undergraduate course and laboratory oversight. I also made a conscious decision to be readily available to students. This demanded empathy and patience and the need to overcome my natural tendency to be somewhat pre-occupied.

My initial plan to change my research field from Magnetic Resonance to Superconductivity was abandoned as a result of an encounter at the end of my very first day at Monash. A PhD student, whose Supervisor was on sabbatical, came and showed me some confusing magnetic resonance research data that he hoped I might be able to explain. I did find a solution fairly quickly, as a result of which I decided to continue where my expertise lay. This opened up research collaboration with a Chemistry colleague that lasted for more than 30 years! About three weeks later, I acquired my first PhD student. Over the years I had many other excellent PhD students, including one from the UK and four from China.

Towards the end of 1990, I was invited to become Head of Department (HOD) from January 1991, initially for six months. This came as a complete surprise! As Monash and the former Chisholm Institute of Technology had merged a few months earlier, my initial task was to ensure a successful amalgamation of the two former Physics Departments. It turned out that I remained HOD for nine years!

In the years leading up to this appointment, I had managed to complete a research text[xi] alongside normal academic duties – lecturing, research, PhD supervision and undergraduate course oversight. I certainly had not entertained any thought of ever becoming HOD and had never sought either power or responsibility for its own sake. My experience gained as Chair of the Melbourne Diocesan Committee on Education for five years, however, stood me in good stead as HOD!

On taking on the responsibilities as HOD, I accepted the authority entrusted to me and sought to exercise it appropriately and responsibly. I reflected on biblical examples of leadership and it was immediately obvious that one of the most important qualities would be my personal integrity and authenticity. As a Christian, I realised that my fundamental task was to serve my colleagues and students without neglecting other professional and Christian responsibilities. It was always a challenge to balance family life, professional commitments and wider church involvements and I maintained Sunday as a day for Worship and rest.

The responsibility as HOD became increasingly difficult because assurances given at the time of the merger that all positions – academic and non-academic – would be secure, proved to be unfounded when, two years later, a new budget model made job losses inevitable. Throughout the remainder of my time as HOD, while much of the necessary staff reduction occurred voluntarily, hard decisions also had to be made. I was not able to avoid the difficult decisions that were my responsibility, or difficult times, but I was always aware that God was with me throughout. That required much prayer as I sought God’s wisdom, time and time again. In fact, there was never a day in which I did not pray for God’s wisdom with James 1:5-6 in mind,

“If any of you is lacking in wisdom, ask God, who gives to all generously and ungrudgingly, and it will be given you. But ask in faith, never doubting,…” (NRSV)

I recall a particular occasion when two colleagues came to see me when we were facing some challenging issue. The conversation began something like this, “You are a Churchman. You are religious. We can trust you!” I hadn’t expected that! And while I wouldn’t have described myself as they did, I understood where they were coming from, and that was reassuring. This confirmed that one to rely on the integrity of one’s life amongst one’s colleagues but without preaching! I suppose this was a healthy reality check!

In recognition of the contribution made by all of the Academic and General Staff, at the end of every year I gave each a Christmas Card with a short message of both thanks and encouragement. This, I learned, was much appreciated.

Of course the role of HOD does not occur in a vacuum and I readily acknowledge those who provided valued support including:- the two very competent colleagues who served as Deputy HOD, the Departmental Secretary, the Laboratory Manager, Budgets Officer, Laboratory Technicians and Heads of the Workshop and the Electronics Workshop. And I also acknowledge my academic colleagues – who showed up for their lectures, tutorials and laboratory classes – and who ensured the quality of our academic programs.

In keeping with the unexpected, during my time as HOD, I also served on the Psychology Review Panel and as Chair of the Academic Board Committee on University Governance.

After nine years as HOD, I knew it was time to step down, particularly to make time for certain national and international obligations. In addition, as I wanted to free up time to address issues at the faith science interface, I took the opportunity to retire three years early. I undertook two courses in Ethics, particularly to think through the ethical and moral dilemmas raised by e.g. stem cell research and cloning, issues that go to the heart of what it means to be human.

Bearing in mind that during my time at Monash, to be a Christian was to be in the minority, I look back with gratitude for many informal lunchtime gatherings of fellow Christian Academics that were a very real encouragement. Another important factor was the weekly Anglican Communion Service in the Monash Chapel. Chaplains Philip Huggins and Barry Rogers proved to be great encouragers!

Once I had made an adult commitment to follow Christ, it became obvious that part of my calling or vocation was to serve others. My earlier experience as Secretary of my School Debating Society and of the University of Canterbury Athletics Club was not wasted. However, many of the opportunities that opened up over the years continued to come as complete surprises[xii]. A colleague asked me one day why I consented to become Honorary Secretary of the Australian Institute of Physics, doing what he thought was simply a chore. I tried to explain to him that I saw this as part of my Christian Vocation, to serve others.

During my honours year, I discovered a great many helpful books, particularly Mere Christianity by CS Lewis[xiii], and Science and Christian Belief by Professor Charles Coulson from Oxford. In Mere Christianity, Lewis presented the case for Christianity in a language I could readily understand. In Science and Christian Belief, Coulson, a most eminent scientist, articulated a coherent understanding of science in the light of his Christian faith. Particular insights from Lewis and Coulson helped me grasp the idea of the unity of knowledge and to welcome the truth whenever and wherever it is found. It also became increasingly clear that the bible was not a science textbook and that one should not look to it for modern scientific concepts.

Around the end of my honours’ year, I was facing an important internal debate as to whether to continue in science or go in some other direction such as ordination[xiv]. One of my Physics Lecturers was a Christian and we agreed to pray about this for two months; our conclusion reached independently was that I should carry on doing what I was doing!

My interest in the relationship between science and Christian faith has been a journey lasting more than six decades! Two foundational texts to which I return time and again are John 1:1-18 and Col 1:15-19. These are powerful theological statements about the centrality of Christ to understanding the world in which we find ourselves. God is the Creator (bearing in mind a Trinitarian understanding) and these texts expose the nature of our relationship to God, to the Creation, to each other and how to understand ourselves, and they provide a motivation for scientific investigation.

I remain committed to the need to integrate the views of the world one obtains from both science and faith perspectives. There is a common misconception that when we peer through our telescopes or down our microscopes, or whatever it is we do as scientists, we are thought to be mainly looking for evidence for the existence of God – what some call Natural Theology. However, what I have come to see is that one operates from a Christian faith position that recognizes the world (i.e. the universe) as possessing an appropriate level of God-ordained order. Part of the mandate of Genesis 1:28 (quoted earlier), at least, is that we have not only the freedom, but also the responsibility, to seek to understand this very universe in which we find ourselves. Put another way, one works within the framework best called a Theology of Nature. While the patterns and regularities we find will often be occasions for awe and wonder[xv], we don’t put God into our scientific explanations or into our equations. To explain is not to explain away as some are inclined to think. Rather it is to recognise that there are different levels of explanation relevant to any phenomena. And in any case, scientific explanations cannot be authoritative about purpose. This is because the metaphysical assumptions underpinning science cannot be located within science itself.

I take the findings of modern science seriously and am convinced that the big picture of our universe and how it operates is well explained by biological evolution and big bang cosmology. Thus, I do not support so-called ‘creation science’ or ‘intelligent design’. Nor do I support ‘God of the Gaps’ arguments and I am reminded of a very insightful quotation from Coulson[xvi], “When we come to the scientifically unknown, our correct policy is not to rejoice because we have found God; it is to become better scientists.”

In seeking to articulate coherence between my faith position and my scientific understanding of the way things are has proved challenging and there remain many ‘untidy edges of my knowledge’. The relationship between science and faith, and science and theology, is perhaps better understood in terms of the processes we use to think about our science and the religious, and philosophical and metaphysical questions that science throws up.

Like so many, I have been a beneficiary of the thought of those many Scientist-Theologians who began their careers in science, particularly, John Polkinghorne and his free will defence. Polkinghorne has also argued for what he calls the free process defence, that is, the universe itself is endowed with the capacity to go on creating itself. His many lectures he presented during three visits to Melbourne during the 1990’s were always insightful, challenging and inspiring[xvii]. I am also much indebted to Alister McGrath[xviii],[xix] for his insights into the nature of reality. These writers and many others challenge the notion that religion is out-of-date in today’s post-modern world. What I have long realised is that we cannot make our faith captive to any particular scientific theory, even though, with Polkinghorne, we can say we have a significant grip on reality. Scientific understanding is always open to subsequent modification.

Over the years there have been many opportunities to speak about Science and Faith to Church, Campus and School Groups. I have always found it a challenge to find a suitable vocabulary when talking to audiences where most have only a hazy understanding of science. When speaking to Campus Christian Groups, I frequently found that much of modern science was not welcomed and subsequent invitations were rare! The stumbling blocks related to evolution and big bang cosmology. It appeared that many of the students belonged to Churches where the Pastors and Ministers held to a creationist position (possibly by default) and didn’t encourage curiosity or questioning. This remains an on-going challenge for organisations like ISCAST. I recall the advice I gave the Theological Students at Ridley College 50 years ago:-

‘My advice to you is – acquire some scientific friends – preferably Christians – let them tackle the real scientific enquiries. I do not believe your task is to be jack of all intellectual trades. This is a mistaken view of the Christian ministry. It is better to say,” I don’t know, but I’ll try to find someone who can help.”’

Many years ago, the Editor of the EPR Newsletter invited me to write about my Christian Faith in the regular Passions Column[xx]. My good friend from Korea, Professor Sung Ho Choh, who is also a Christian, found this a most encouraging departure from the usual accounts of hobbies and cultural interests etc.

Opportunities for service have also occurred particularly within the Anglican Church[xxi]. For about 30 years I have contributed book reviews, single author articles and joint articles at the faith-science interface for The Melbourne Anglican (TMA) and its predecessor See. In 2018 I was privileged to co-edit A Reckless God? Currents and Challenges in the Christian Conversation with Science[xxii] with Fellow ISCASTians, Chris Mulherin and Stephen Ames, and the former TMA Editor, Roland Ashby.

I counted it a great privilege to serve as President of ISCAST from 2006 to 2009, a transition period when ISCAST began to discover a true national identity in addition to what had already been realised through the biennial COSACs. My experience of Board Membership on and off over many years put me in a good position to write a recent History of ISCAST (See ISCAST https://iscast.org).

Conclusions

This essay has challenged me to reflect on how the kingdom of God is worked out in the workplace as I experienced it. I am grateful for those many Christians throughout my life who have been great examples as to how to behave in the professions and in business. As a doctoral student in Oxford, I remain grateful for the example of late Sir John Houghton. I had the privilege of working under him as a Laboratory Demonstrator in the undergraduate Electricity Lab at Oxford.

I am convinced that science is not ‘all there is’ (scientism) and that Christianity provides a necessary and complementary means of looking at ourselves and the world. However, it is important for us not to be mesmerised by what we have discovered through science, though of course modern civilisation depends so much upon it, but still to be able to appreciate a beautiful sunrise or sunset or a Bach Cantata or a Beethoven Symphony. There is, of course, so much that is not explained by or encompassed within science.

As I have pondered the influences during my life, especially while growing up, I can see that God’s particular plan for me was beginning to take shape. My career was many-faceted with lots of unexpected twists and turns. And as I look back, I can see that even when I was only 7 or 8 years old, I was beginning to head towards science.

As I have tried to explain, many of the responsibilities that came my way were totally unexpected and thus my career turned out somewhat differently from what I had imagined as a schoolboy. I can say quite honestly that as a Christian I was able to make the responsibilities and challenges matters for daily prayer. In seeking to discharge those responsibilities, as well as those of being an academic teacher and researcher, was always an outworking of my Christian faith.

Personal reflections such as this are a challenge. It would have been good to have had a reality check from those who were colleagues for some or nearly all of the 36 plus 10 years at Monash. I shared one example. On the occasion of my retirement, I was glad that the colleague who spoke about my time at Monash referred to me as a ‘Committed Christian’. It is true, there had been no place to hide!

Acknowledgements

My journey would not have been possible without the love, support and encouragement of Susan, my wife of more than 59 years. We met as students at Canterbury University. We have sought to live consistently as Christians throughout our marriage and we have been blessed with a large family. Our two US sabbaticals, travelling with all our children, would not have been possible without Susan’s skilful organisation and management!

[i] Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, similar to the CSIRO.

[ii] Until 1958 it was Canterbury College of the University of NZ. For simplicity I refer to it throughout as the University of Canterbury.

[iii] EPR (Electron Paramagnetic Resonance), sometimes called ESR (Electron Spin Resonance) is a branch of Magnetic Resonance concerned with electron resonances in a magnetic field. NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) and its application to medicine (MRI or Magnetic Resonance Imaging) involve nuclear resonances.

[iv] Professor Robin Carrell FRS, Emeritus Professor of Hematology, Cambridge.

[v] Author of several Pelican Books popularising Mathematics including Mathematician’s Delight (1943) & Prelude to Mathematics (1955). During my last year at school, Sawyer asked me to comment on the Galley Proof of Prelude to Mathematics prior to publication. Until then I had never heard of Galley Proofs!

[vi] Many viruses including flu viruses have a basic icosahedral structure with, of course, lots of other molecules attached to the outside.

[vii] Some might call this an epiphany. I have not had such an experience again.

[viii] Rev Prof David Wilkinson, Principal, St John’s College Durham, from his BBC Sunday Worship 19June2016 and published in Science & Christian Belief 43 (2017)

“That is why for those of us who are scientists and Christians the passage from Paul’s letter to the Colossians is so important. Paul says that in Christ ‘all things cohere’ or ‘all things hold together’. This is for me a Christian affirmation of science or, as my colleague here in Durham Tom McLeish, Professor of Physics, stresses, a theology of science. It indicates that the scientific laws, however vaguely we understand them, find their origin and continued existence in the creative work of God in Christ. The unity and regular patterns we see in the universe and by which we work with the universe in technology are there as a gift from God.

That means that to be a scientist or engineer, either in research or in teaching, is a Christian calling. Too often the Christian church has made the mistake of believing that God only calls people to be missionaries or priests. Churches need to rejoice over those students who are studying science, those who teach science in schools or universities and those who are pushing the frontiers of science, whether it be in artificial intelligence, gene editing or the search for extraterrestrial life. Such things may raise important questions for faith, and faith may want to raise important questions back to the science – but I am convinced that the conversation is not to be feared and will be fruitful.”

[ix] Regrettably, Sir John died recently from complications due to Covid-19! His example as a Christian, and young and senior academic, remained with me as a model for my own career. Sir John was also awarded the Japan Prize in 2006 for his contributions to global warming and climate change.

[x] Steady State Cosmology was the brainchild of Bondi in collaboration with Fred Hoyle (Cambridge) and Thomas Gold (Cornell) but the theory fell into disrepute after 1964. Big Bang Cosmology leads to our universe being ~ 13.8 Billion years old. The question of a Creator actually lies outside science.

[xi] Transition Ion Electron Paramagnetic Resonance, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1990), 711pp.

[xii] Organising Secretary for the International Symposium on Electron and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance[xii](held at Monash University August 1969); Hon. Secretary, Australian Institute of Physics (AIP) 1976-77; AIP President 1999-2000, a period when the Annual Scientists Meet the Parliament meetings were just beginning; Hon Secretary, International EPR/ESR Society (IES), during which time I rewrote its Constitution, grateful for my previous experience 40 years earlier in rewriting the Constitution of the University of Canterbury Athletics Club; IES President 1999-2002; ISCAST President 2006-9.

[xiii] I first read all of Lewis’s published writing relating to Christianity more than six decades ago. During our 1979 US sabbatical in Milwaukee, where I was a Visiting Professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Susan and I joined the CS Lewis Society. This was a book reading club consisting of some 70 members, mostly Christians ranging from Catholic to Pentecostal. They all acknowledged that they could not have that kind of discussion in their local churches! We enjoyed lively discussions of Lewis’s thought, particularly his imagining of other worlds. Some Graduate Students of English Literature from the local university had been encouraged by their Professor to attend so as to discover what Christians thought!

[xiv] In the late 1950’s in certain Christian circles there seemed to be a hierarchy of suitable occupations for Christians. High on the list was ‘full-time service’ e.g. ordination, missionary work. But medicine, nursing and teaching were OK. Science as a career was not really mentioned or understood! It is sad to think that how Christians spend much of their lives is not celebrated in most Churches.

[xv] For helpful insights regarding awe and wonder and related concepts, see Alister McGrath, Dawkins’ God: Genes, Memes and the Meaning of Life, Blackwell (2007) and Tom McLeish, Faith & Wisdom in Science, Oxford (2014)

[xvi] Coulson, C. A. (1955) Science and Religion: A Changing Relationship. Cambridge: CUP, p.2).

[xvii] Polkinghorne’s visits to Australia in 1993 and 1996 were jointly supported by ISCAST and the British Council.

[xviii] Currently the Andreas Idros Professor of the History and Philosophy of Science at Oxford.

[xix] McGrath’s visit to Australia in 2007 as keynote speaker at COSAC2007 was sponsored by ISCAST.

[xx] Pilbrow, Passions Column, EPR Newsletter 16 (1), 2006, pp 10-11.

[xxi] These include: – Member, General Synod (1985-93); Chairman, Melbourne Diocesan Education Committee 1985-1990; Deputy Chair, Melbourne Anglican Committee for Christianity & Atheism 2010-12.

[xxii] Jointly published by ISCAST and TMA.