An Expanded Address at All Saints School Commencement Service, February 2nd, 2018. The address was pitched at year 11 and 12 students and staff. Finalised 5th February 2018

Professor David Goldney

Biography

David Charles Goldney was born in Adelaide, South Australia, the youngest of six children and a fifth generation Australian. His father was a Methodist Minister and his mother actively involved in fledgling women’s movements.

David grew up in a house that was filled with music, books and parents who encouraged all of their children to be the first generation to receive a university education. David attended Adelaide University from 1958 to1962 where he completed a science degree majoring in Botany and Biochemistry. David later completed a Graduate Diploma in Education. David met his future wife and long-time partner of 35 years, Joan Chapman, at the Mount Barker High School in the Adelaide Hills, and they married in 1965. Joan and David have two children—Alex and Jodie.

In 1968 David accepted a tutorship in the Botany Department of the University of Queensland, enrolling concurrently for a Master’s Qualifying exam and gaining first class honours. He then gained a Commonwealth Postgraduate Scholarship and enrolled as a Doctoral student, investigating the role of ethylene in the ageing of leaves. In 1972 David accepted a science lectureship at the newly established Mitchell College of Advanced Education (MCAE) in Bathurst, planning to live in this provincial city for three years before moving back to Adelaide. Thirty years later, he and Joan are established “Bathurstians”.

Despite high teaching loads and the underlying philosophy of CAE’s not to encourage research, David and a number of colleagues set up a range of research projects and actively involved student teachers in field ecology programs. With the help of grants from the Commonwealth Government and the National Trust, David provided the first overview of the conservation values of the Central Western Region. By the mid-1980s he had carried out defining studies on the distribution, abundance and status of every vertebrate species in the region and had set up long-term vertebrate studies and sites that continue to this day, including one of only two mark-recapture-release studies of platypuses in Australia in 1986.

During the 1980s, David began to conceptualise his understanding of the relationships between nature conservation and production agriculture and to alert the community through public speaking, newspaper articles and media appearances, about the interconnected twin evils of land degradation and biodiversity losses across the major agricultural landscapes of Australia. His central thesis that the process underlying Australian agricultural landscapes is ‘desertification’ was a prophetic call, not always received kindly, but now with salination rampant and agricultural landscapes malfunctioning, one that is widely accepted.

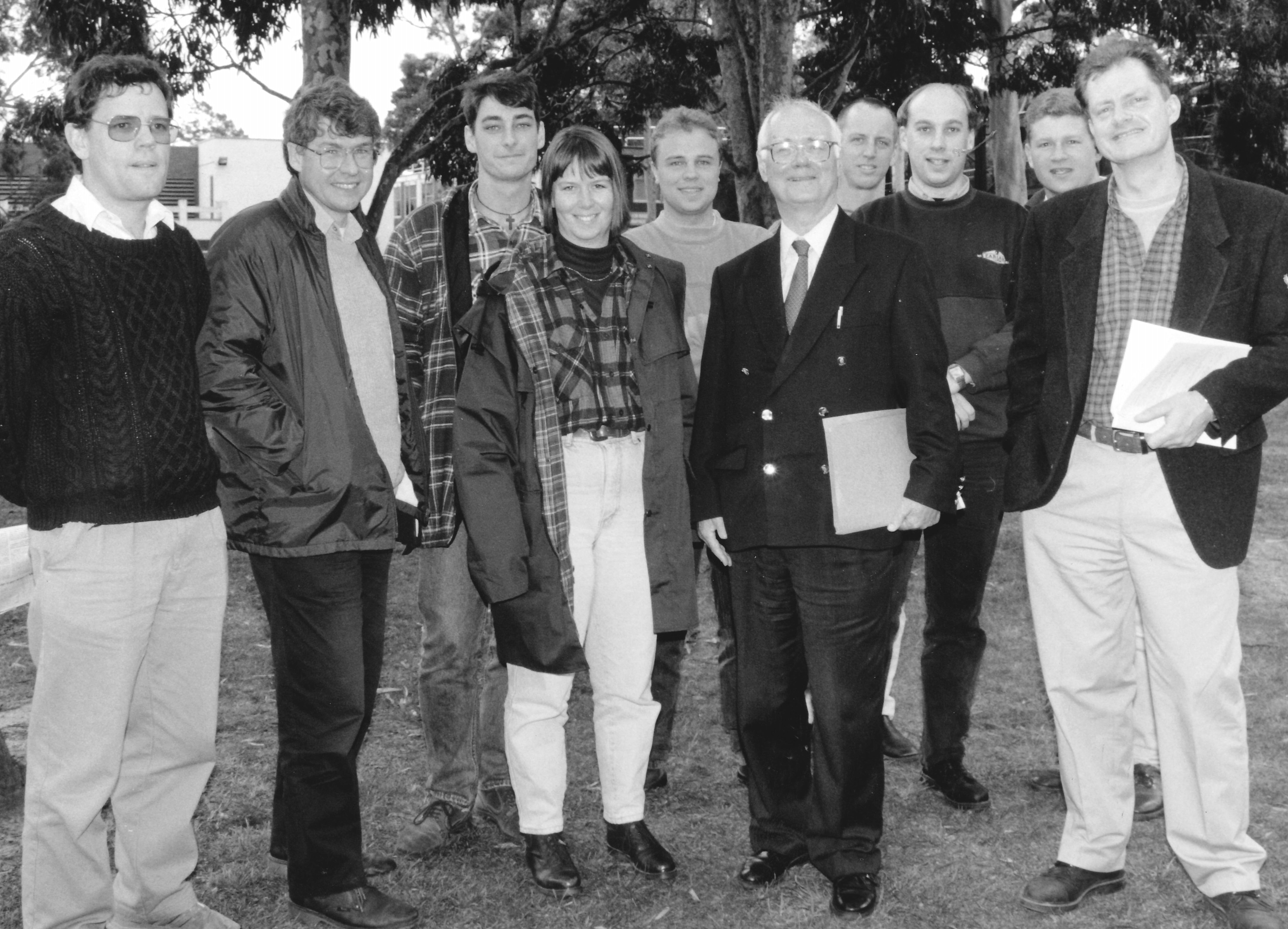

Over the last 20 years David has spoken to thousands of landholders. This culminated in the major publication of a ‘Save the Bush Toolkit’ in 1997, a team effort driven by David to facilitate landholders using simple but effective observation methods to assess their farms’ natural resources and to instigate repair measures where possible. The dissolution of the CAE sector and the formation of Charles Sturt University provided David with the chance to work with postgraduate students and a range of staff from other disciplines across the university campuses, in an environment that encouraged and recognised the value of research. David developed a number of multi-disciplinary research teams to investigate the links between nature conservation and production agriculture.

In 1996, he received an award for Outstanding Contribution to Environmental education from the Government of NSW. David is a member of seven learned societies, on the editorial boards of two international journals as well as a referee on a regular basis for many others, and is a member of numerous natural resource committees. He was the foundation head of the Environmental Studies Unit and an Associate Director and later Director from 1997 – 1999 of the Johnstone Centre, one of the largest designated research centres within the university.

David has published widely in academic journals as well as regularly communicating important scientific outcomes via the media to the general public. He has 43 refereed publications, is the joint author of three major conference proceedings, has given over 50 conference presentations, is the author of 27 major consulting reports for national and international companies plus numerous minor reports for councils and conservation groups.

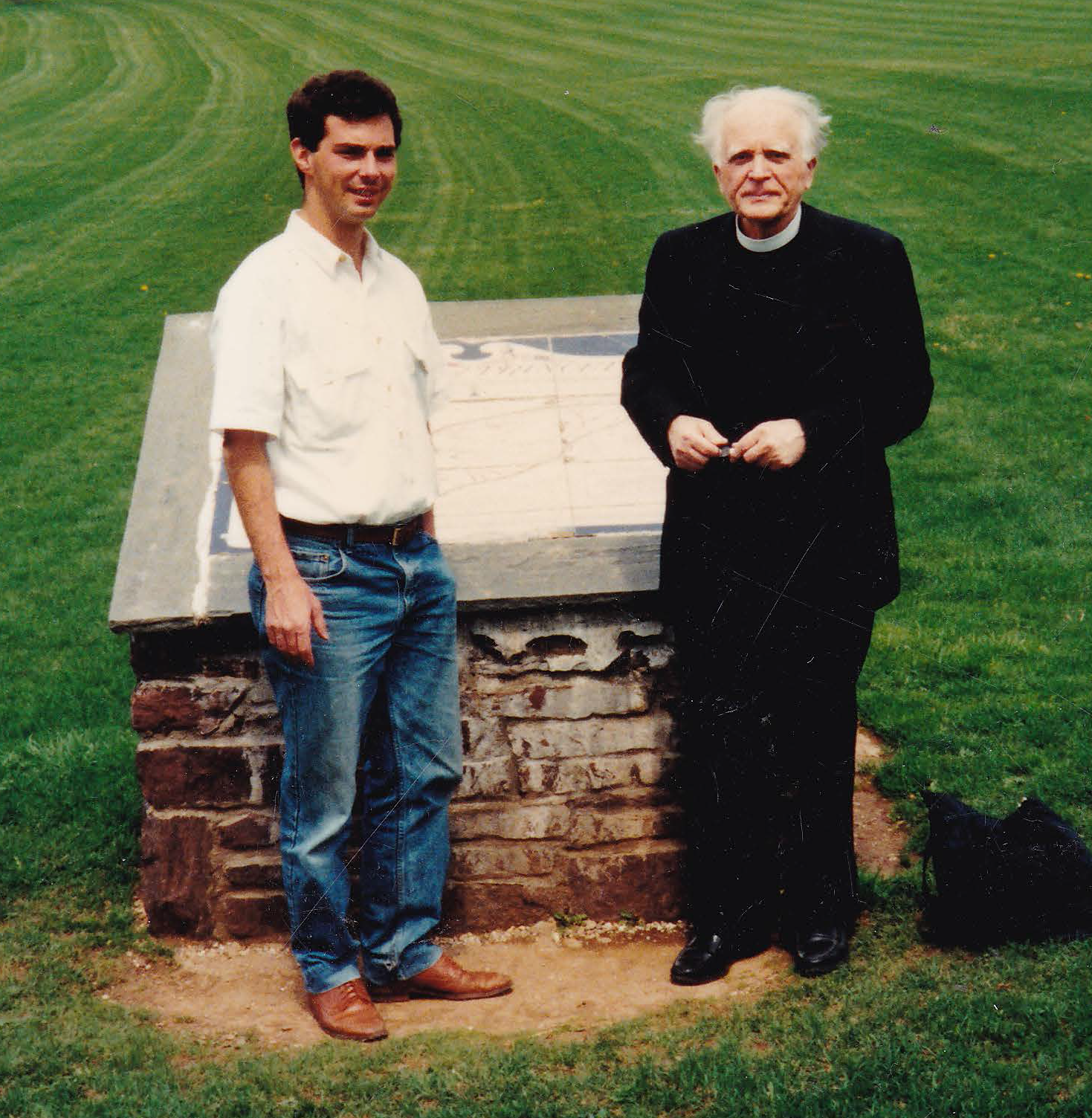

David is very active in a range of community activities including the Uniting Church where he is a lay reader, the National Trust of which he is a member, Amnesty International and numerous conservation groups. He is Deputy Chair of the Central West Catchment Management Committee. Since his retirement from the university David has been appointed a Professorial Associate and continues to supervise postgraduate students on a part-time basis as well as remaining actively involved in ongoing research. David has been granted a travelling fellowship worth $28,000 by the Commonwealth Government to investigate “the integration of nature conservation and production agriculture” in North America, the United Kingdom and Northern Europe and to report back to governments on the relevance to Australia’s worsening land degradation and bio-diversity losses scenarios.

Introduction

I am a hard-nosed scientist, a wildlife ecologist, an academic given to rational thought and logic. I am also a committed Christian in the Evangelical1 tradition. My faith and my science are well integrated rather than being artificially kept in separate compartments. People often ask me How can you be a Christian and a scientist—aren’t they mutually exclusive? I am in good company with thousands of men and women scientists from nearly every nation on earth who share my faith, from Nobel prize winners to the inventor of the Bionic Ear in Australia.

When the scientific revolution exploded in Christian Europe in the 17th C, Christians were at the forefront in facilitating this life changing movement. The scientific revolution was able to flourish in a Christian culture for many reasons including belief in four simple propositions:

- There is a Creator God who brings the universe into being;

- The Creation is Good;

- The Creator (God) is other than his creation; and

- The universe is ordered and its processes can be understood.

Christianity never embraced Pantheism2. Hence when the thunder rumbles and lightning strikes, we can look for rational and natural explanations about these phenomena or any other happening for that matter, rather than see them as perhaps expressions of an angry god, or even irrational magical processes. Aristotelian thinking (from 350 BC to around 1600) gave way to questioning and hypothesising, unleashing the power of experimental science.

When I was beginning my academic journey at the University of Adelaide in the late 1950s the prevailing scientific world view saw the universe as being in a steady state—unchanging—a view championed by the atheist astronomer Sir Fred Hoyle, since it appeared to do away with the notion of a Creation and therefore a Creator. The proposition was that the universe had always been there! It was the Belgian Catholic astronomer priest, Professor Georges Lemaître, who proposed a different model, and bequeathed to us the notion of the Big Bang theory and the ever-expanding universe, the very antithesis of the Steady State theory. One of the arguments used by Hoyle to ridicule the Big Bang theory was that it would, if true, allow the Christian Genesis story some wriggle room. Indeed.

Let me introduce you briefly to one of the fathers of the scientific revolution, a German Lutheran Christian born in 1646—Gottfried Leibniz. He was a mathematician, philosopher, physicist and psychologist. He, along with Newton, independently invented calculus and the binary system at the heart of modern computing. He is regarded today as a genius. One of his legacies was to ask what is now agreed to be one of the great metaphysical questions of all time and one that none of us can escape asking—

Why is there something rather than nothing?

It is a deceptively simple but nevertheless a very profound and timeless question. Furthermore, as people living in the 21st C we might also want to ponder on other questions such as: Do we live in a universe that is the product of blind chance or does it demonstrate purpose? Was there a “beginning” and what was before the “beginning”? And is our planet in the “Goldilocks Zone”3of the solar system, the result of a chance series of events, or is this too consistent with a purposeful universe? Leibniz’s compelling question is with us in our waking and in our dying. Reflecting on his and other such questions provides us with clues that at least raise the possibility that there might just be a ‘god’ somewhere, a Ground of Being who brings all things into existence. Leibniz thought so.

A contemporary of Leibniz was another universal genius and fermenter of the Scientific Revolution, also a convinced Christian—Blaise Pascal. He proposed a Wager—

God is, or He is not. But to which side shall we incline?

Is it heads or is it tails? In today’s parlance we think in terms of:

- atheism (there is no god),

- agnosticism (I do not know if there is or is not a god),

- theism (There is a God – a Ground of Being who is active in the world) or perhaps

- Deism (There is a god but he remains aloof from the world and having created it leaves it to its own devices).

Pascal also encourages us to explore the possibility of God communicating with us in multiple ways including through Word of God in Scripture and Word of God in Nature. I suspect that most of us at some stage in our life pilgrimage will of necessity consider atheism, agnosticism, theism or deism as our basis for living. I know that as a teenager I went through that harrowing but necessary process.

Johannes Kepler, a German Lutheran Christian born in 1571, the father of physical astronomy, first described his three laws of planetary motion, and in one fell swoop, took the study of the night sky from the superstitious fear that gripped the hearts and minds of the common people and scholars alike, to rational investigation, and in the process believed that he was thinking God’s thoughts after him.

Sir Isaac Newton, often thought of as the greatest scientist who has ever lived, also had a well-articulated Christian world view. He built on Kepler’s knowledge base to create his theory of universal gravity and the three laws of motion. Whilst understandably he had a very mechanical view of the solar system, he nevertheless saw God’s hand at work.

That brings me now to consider briefly the scripture reading we have just listened to from St Paul’s letter to the Church in Corinth—And now these three remain: Faith, Hope and Love and the greatest of these is love.

Faith

The atheist astronomer the late Carl Sagan, a brilliant interpreter of the heavens, once said that Faith is believing in something in the absence of evidence. The atheist author of the God Delusion labels Christians as Faith-heads. I beg to differ—rather I see Christian faith as a leap of the imagination4 and never a leap based on absence of evidence. As the writer to the Hebrews puts it—faith is the evidence of things not seen.

Let me explain. For hundreds of years people saw the stationary earth as the centre of the solar system until Copernicus came up with a revolutionary understanding that saw the sun as the centre of the solar system with the planets, including the earth, revolving around it. This was a brilliant leap of the imagination—he could not actually see his model he could only imagine it, and then test his understanding through making predictions—if you like “the evidence of things not seen”. This revolutionary understanding represented what scientists call a paradigm shift, seeing natural phenomena in a radically different way. Once we were blind to reality—now we see the world differently. Facts remain the same and are always available, but often make little sense unless we are able to connect the dots into a pattern of understanding—somewhat like looking at a random ink blot and suddenly realising that it is actually someone’s face—a Eureka moment.

The Eureka Moment for one-time atheist Professor C.S. Lewis who has enriched all of our lives with his children’s stories or through his other writings, occurred spontaneously as a passenger on the upper storey of a London double decker bus. There he met God—Ground of Being, or as he puts it in the title of his book—he was Surprised by Joy. The penny dropped after having been constantly followed by in his words, the Hound of Heaven. This was his leap of the imagination. Biblical writers often see this moment as “once I was blind, but now I see”—what was previously just an “ink blot” is transformed into looking at reality in a completely different way. Coming to faith enables us to see reality differently, and embrace a revolutionary world view. It does not usher in an era of logical certainty, that is not open to any of us—one reason why I find it difficult to understand the logic of atheism. Faith does however enable us to enter the world of psychological certainty.

Hope

We all hope for so many things, perhaps a better world, or maybe to make a lot of money, or perhaps to become Prime Minister or to do well in the HSC. There is nothing necessarily wrong with any of these hopes! Christian hope is however somewhat differently nuanced. It draws its inspiration from the prophets and imagines a possible future (eschatology) where broken relationships are healed at multiple levels—between God and humans, individual brokenness, the breakdown in international order, and the broken relationship between humans and nature. Scripture couches hope in the language of the Kingdom of God being amongst us and the vision of a New Heaven and Earth, where the wolf lies down with the lamb5 and where justice rolls down like an everlasting stream6. The prophetic intent is to name evil and to work towards it eradication.

Let me give you two examples from my faith tradition. Some of my forebears were Bible Christians in Adelaide, one of the three major divisions of Methodism in colonial Australia that eventually merged to form the Methodist Church of Australia. It is now subsumed within the Uniting Church of Australia. Bible Christians in the 19th C encouraged women to be involved in ministry, forbidden in most other denominations. Serena Thorne, a talented female Bible Christian evangelist, migrated to Adelaide around 1860 where she drew large crowds to hear her speak. She married Octavius Lake a Bible Christian minister only after he promised to accept the right of women to be preachers, and to recognise the equality of women and men before God. Serena, now Serena Lake was a feminist and a leader of the Suffragette Movement and helped bring the vote to South Australian women, as well as their right to stand for parliament. She was also a leader in the Temperance Movement since it was male drunkenness that was the root cause of the epidemic of domestic violence in colonial Australia as well as in Great Britain. Serena’s husband, Octavius, was my Father’s theology teacher and through him her feminist theology and practices were formative in his subsequent ministry.

In the little village of Tolpuddle in Dorset around 1834, John Loveless along with five other Methodist laymen formed a Union to seek better pay and conditions for farm labourers. It was likely that John was illiterate until he became a Christian during the period of Methodist revivals, and was taught to read and write in weekly Methodist Class meetings. Laypeople were also taught to lead meetings and to speak in public. John and his other union leaders were convicted of swearing a secret oath and sentenced to deportation to Australia as convicts in 1834, but due to a public outcry were eventually pardoned and returned to Dorset as freemen. They became known as the Tolpuddle Martyrs. Through their actions for justice they helped facilitate the formation of the British Labour Party. Methodism was also very influential in the formation of the Australian Labor Party.

Faith enables us to see reality from a novel perspective and Hope enables us as the Body of Christ to facilitate the healing of broken relationships and to seek justice in all the world. But are Faith and Hope enough?

Faith, Hope and Love – The Greatest of These Is Love

Thomas Merton, an influential Catholic Trappist monk, once claimed I believe in Nothing. In writing about his Cambridge University education, he says: I laboured to enslave myself in the bonds of my own intolerable disgust. His conversion and Eureka moment is outlined in his biography, Seven Storey Mountain. Faith will open the door to a New Order, Hope will sensitise us to the universal cry for Justice, but it is Agape Love7that is at the heart of the Gospel, The Good News of the Jesus story. Merton reflecting on this writes: To say that I am made in the image of God is to say that love is the reason for my existence, for God is love. Love is my true identity. Selflessness is my true self. Love is my true character. Love is my name.

“God is love” is the fundamental tenet of the Christian world view, God being expressed as Father, Son, and Spirit, not a mathematical formula, but rather humans struggling to understand the different ways that God reveals himself to us. Perhaps the best analogy that helps us understand this is to think about light that comes to us each moment as past, present and future, but still remains one light. The revolutionary Jesus story, God amongst us, comes to us with multiple paradoxes that can challenge our pre-conceived ideas of what life is all about. If you want to live life abundantly you must be prepared to lose your life. If you want to be in a relationship with Ultimate Reality, Ground of Being, God, and throb in sync with a universal Agape Love you need to be prepared to die to self and to rise again as a person who now sees the world differently. That by the Grace of God is a paradigm shift that Christians call conversion and Jesus compared to being “Born Again”.

I wish you well in your life pilgrimage here at this moment at All Saints School. If you truly seek Truth you will surely find it and the Truth will make you free.

ENDNOTES FOR GOLDNEY

1 The term Evangelical is entrenched within religious culture wars – I am referring specifically to the tradition that gave us William Wilberforce (abolishing slavery), the Tolpuddle Martyrs (6 Methodist Laymen transported to Australia for seeking fair wages for English workers), Serena Lake in South Australia—a leading figure in the Suffragette movement), Dietrich Bonhoeffer (stood against the Nazi Regime), Martin Luther King who led the USA Civil Rights movement in the 1970s), Nelson Mandela—the first Black President of South Africa, Archbishop Desmond Tutu who courageously stood against apartheid in South Africa, and atheist Professor C.S. Lewis, turned Christian – Christianity’s greatest apologist in the 20th C.

2 Pantheism is the belief that all reality is identical with God—so a tree is part of God as is a rock, as is a human and a spider. Christians see God as Creator but other than his creation

3 The distance of earth from the sun, where it not too hot nor too cold to support life – is this purpose or chance?

4 The writer to the Hebrews Chapter 11 put it this way—Faith is the evidence of things not seen, the substance of things hoped for….

5 Isaiah 11:-9, esp v6.

6 Amos 5:24

7 Agape Love is a sacrificial love that voluntarily suffers inconvenience, discomfort, and even death for the benefit of another without expecting anything in return.