In the beginning was the Word,

the Word was with God,

and the Word was God.

He was with God in the beginning.

Through him all things came to be,

not one thing had its being but through him.

All that came to be had life in him

and that life was the light of men,

a light that shines in the dark,

a light that darkness could not overpower.The Word was made flesh,

he lived among us… (John 1:1-3, 14)

So reads the Gospel on Christmas Day. Like me, you might wonder about the meaning of these words, as they are very poetic but somewhat obscure to the average layperson in the pews. Why is Jesus in the manger called “the Word”? And what does Christmas have to do with science, as the title of this article implies?

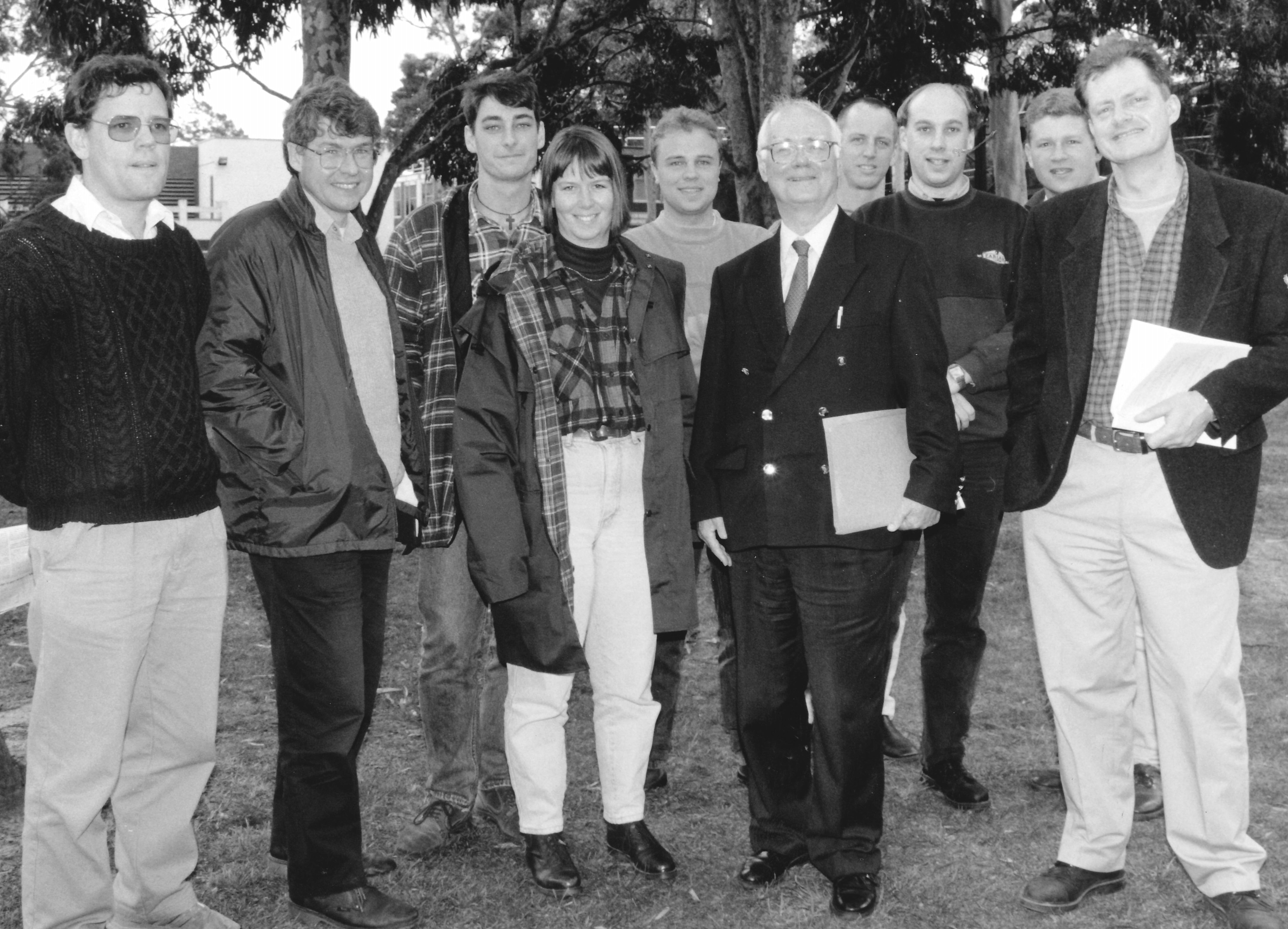

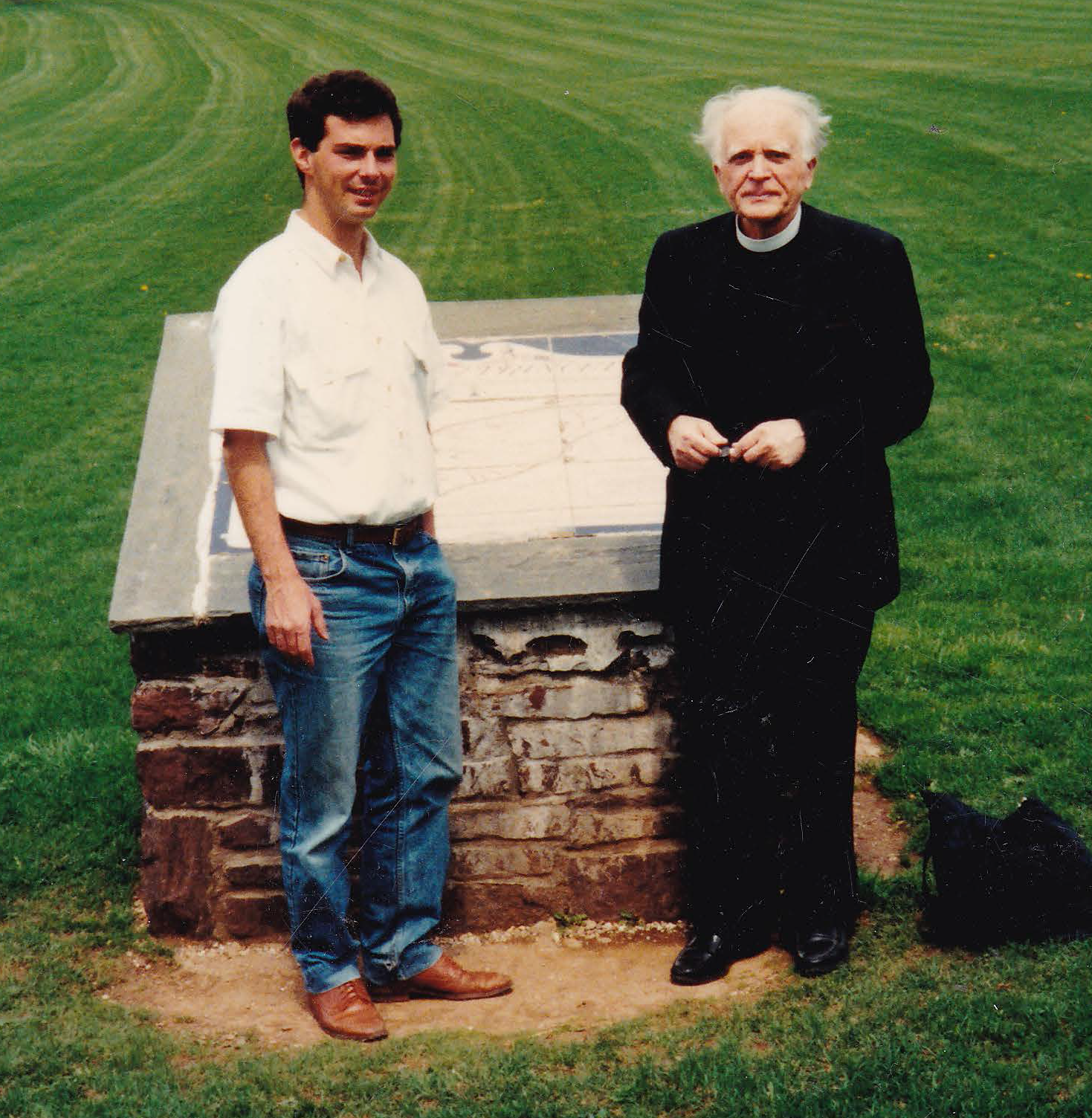

I found the answer to both questions in the writings of Father Stanley Jaki, a physicist, historian, philosopher; and a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences up to his death in 2009. Father Jaki was author to over 40 books linking science (physics in particular) and its discovery to Christian faith, doctrine, and culture. As Anna Krohn wrote about Jaki in the Catholic Weekly a few years ago (12 April 2017): “Jaki argues that Christian theology was crucial for the rational origins of scientific exploration and discovery. Faith in turn, inspires the lives, the commitments and moral compass of Christian scientists.”

Jaki’s key claim is that after several false starts in several great ancient cultures, the discovery of science in general, and physics in particular, grew from philosophical seeds planted by a Christian culture, and cultivated by the great Christian minds leading up to the Middle Ages and early Renaissance. Central to his story are two critical items of faith: first, everything “in heaven and on earth” (the universe) was created by God, from nothing (ex nihilo) and in time. Second is God’s becoming man, being born of Mary in Bethlehem. Indeed, in his book The Savior of Science, Jaki refers to the first Christmas as “the Birth that saved science.”

What madness is this? To understand his point we need to look at the philosophy that dominated the Mediterranean around that time, a rich tradition from the Greeks, beginning with Socrates, taught by Plato, and applied to the physical world by Aristotle. The scientific revolution could not occur if civilisation did not really trust nature, if no one believed that nature was consistent and rational.

For most ancient cultures, the physical world on earth was not particularly trustworthy. It certainly was not held to follow any specific laws. Nature was more like an animal, with a will of its own, not a machine as was held by the time of the Renaissance and early Enlightenment. The only ancient people who widely believed in the reliability of nature were the Jews. The Old Testament has numerous passages, such as in the psalms, Job, and Jeremiah, linking the regularity of nature to God’s covenant with his people.

Beginning with Socrates, the Greeks looked for a purpose in everything, and that which was good, whether it be in human affairs or in nature, was linked to its acting for a purpose. Aristotle applied this thinking to nature and to the physical world. His interpretation of the universe, both on earth and in the heavens, dominated natural philosophy for over 1500 years. Up to the late Middle Ages, it was the lens through which scientific, astronomical, and even mathematical discoveries were viewed. Any theory that contradicted Aristotle was at the very least looked on with suspicion and more often condemned.

A key element of Aristotle’s philosophy was pantheism, the notion that nature and the universe itself are divine and eternal. Various aspects of nature were personified by individual gods, such as Zeus or Poseidon. In the absence of divine revelation, this is not necessarily an unreasonable proposition. One of the results of Aristotle’s philosophy is that for the Greeks at the time, the sphere of the fixed stars and planets shared that divinity. The earth, on the other hand, was fundamentally different, imperfect, and governed by a completely different set of principles. So for example an object’s purpose was to fall towards the earth’s centre. Heavier objects contained more “purpose” than lighter ones, and thus fell faster. Objects in motion had to be pushed, even freely flying projectiles. In contrast, bodies in the heavens moved in perfect circles, for all eternity, without the corruption seen in earthly objects.

The trouble with Aristotle’s physics is that it was wrong. It was a philosophy, but not science. As the English historian David Wooten notes in his The Invention of Science: A New History of the Scientific Revolution, “There are no Aristotelian laws of nature.” The scientific revolution, as is well known, occurred when the Christian West abandoned Aristotle’s viewpoint. The Greeks would have considered preposterous, even heretical, the story of Isaac Newton, who, after the apple fell (perhaps not on his head), wondered if the motions of the apple and the moon resulted from the same kind of force.

What does this have to do with Christmas? According to Jaki, a great deal. Mere mortals had to abandon the idea that nature and the cosmos were divine in order to have the psychological confidence necessary to search in earnest for nature’s secrets, and so that one scientific discovery would lead to the next. He says that both Islamic and post-Christian Jewish philosophers, while believing in a single, personal God, still found it difficult to abandon pantheism entirely, especially the eternal and divine nature of the cosmos. What then is different about Christianity? In short, it’s Jesus Christ and his Incarnation, which acted as a silver bullet to Greek pantheism.

In the Christmas gospel, Christ is called “the Word”. In Greek, the technical term is Logos. According to Greek philosophy, the Logos was the rational principle that governs the universe. It was a bridge, a crossover, between the divine “Unmoved Mover,” the closest that the Greeks could get to God, and the physical world. The cosmos and the physical world were “begotten” or emanated from the divine, and thus share in its divinity. In Greek the word is monogenes.

St. John, St. Paul and the Christian Fathers emphatically rejected that the physical universe was begotten from the divine through the Logos. Jesus Christ, a man, is divine. He was begotten from the Father, and with him through the Holy Spirit, created the universe. It took the Church hundreds of years to work this point out in detail, and it was a key argument used to convert the Romans to Christianity. “Begotten” shows up twice in the Nicene creed and once in the Gloria, recited every Sunday in many Christian churches. It is also a key concept necessary to gain the confidence necessary to study nature. In his book The Only Chaos and Other Essays, Jaki puts this brilliantly: “John’s use of [monogenes] dethroned the cosmos and saved it by the same stroke. By putting a flesh-and-blood being on the pedestal of monogenes, John erected a powerful barrier against pantheistic emanationism.” St. Paul says something similar in his epistles.

The universe is no longer God. It was created by God, and found to be good, that is, rational and consistent. The heavens and the earth may not be fundamentally different after all, a key point made in the 14th century by the Frenchman John Buridan, who proposed the theory of impetus that later developed into Newton’s First Law.

This is an amazing story, and if this physicist finds it inspiring, that is a gross understatement. In The Origin of Science and the Science of its Origin, Jaki sums up this story: The only worldview that had the ability to generate a scientific revolution was “a view of which the principle disseminator was the Gospel itself. It was the Gospel that turned into a widely shared conviction the belief in the Father, maker of all things visible and invisible, who created all in the beginning and disposed everything in measure, number, and weight (Wisdom 11:27): that is, with a rigorous consistency and rationality.” After several “stillbirths” in numerous ancient cultures, science was born within a firmly Christian context.

John’s reference to Jesus as “the true light that enlightens all men” (v. 9) may refer to more than spiritual or cultural enlightenment. So this Christmas season as you enter a church, and reach into your pocket to put your phone on silent, spare a thought of thanks to the Babe in the manger, for the amazing science that sits unnoticed in that little package, for the grace we received to discover it, and without which your world would turn upside down.