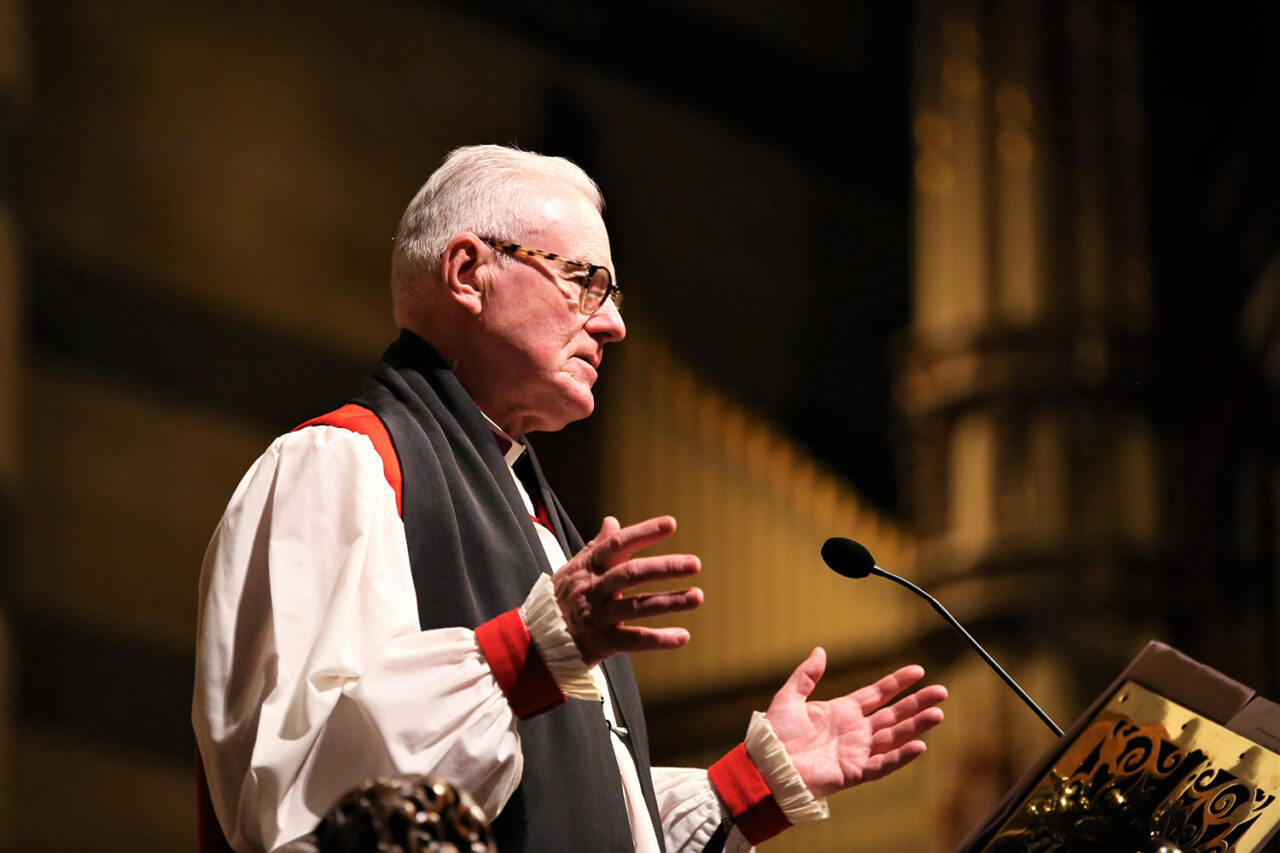

It’s not every day you hear a cathedral choir singing praises to God for the sciences, and even rarer to hear a sermon from an Archbishop about science–faith harmony.

The following was preached by Archbishop Philip Freier on the opening day of the 23rd International Congress of Genetics at a science–faith themed Evensong service at St Paul’s Cathedral, Melbourne.

16 July 2023

It is good to gather here this afternoon in celebration of the 23rd International Congress of Genetics. It was a little over 14 years ago that another international gathering of scientists took place in this cathedral on 8 February 2009 to observe the 200th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s birth and the 150th anniversary of the publication of his book, On the Origin of Species. We are just days from the 201st anniversary of Gregor Mendel’s birth, and, with these two pioneers, Darwin and Mendel, we have the foundations of the disciplines that emerged out of the early field of evolutionary biology: a field of science that brought together Darwin’s work on natural selection and Mendel’s work on the heritability of observable characteristics. Whilst Darwin was ignorant of Mendel’s work, Mendel knew Darwin’s and could see the rich opportunity that would come with the integration of their insights.

You have an ambitious theme for your congress, Genetics and Genomics: Linking Life and Society. Christian faith is part of the societies where its believers are found, and it is good for us to reflect on the question of life itself and the smaller subset of its expression in human society. It is part of our humanity that we strive for understanding and then to translate that understanding into technologies of various kinds.

We have all heard versions of the contemporary assumption that Christianity is a movement in conflict with scientific knowledge and responsible for leading people into dumb ignorance. I think that this could not be further from the truth even though Christians amongst others are engaged in the ethical questions that arise out of the some of the technological applications in the field of genetics and genomics.

I want to develop the position, as I suspect many of you already have accepted, that Christian faith and scientific endeavour are not mutually incompatible. I say this in full consciousness that Christian faith has a foundational understanding of God as Creator, something that we have expressed in the beautiful eloquence of the prologue to St John’s Gospel:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being in him was life, and the life was the light of all people. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.

From the book of Genesis to the Psalms and through to the promise of a new heaven and new earth in the book of Revelation, the theological conviction that God is creator, and the measure of all things is inescapable. We should in no way be surprised that the creed commences with this affirmation: “I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.”

It thus makes sense to look at the doctrine of creation if we are to consider the wisdom of the church and how we might frame an understanding of faith’s relationship with science. Oliver Quick, writing in 1938 just before he became the Regius Professor of Divinity at Oxford, recalled the attitude, prevalent in that pre-war period that, “Darwin’s Origin of Species is [considered] today a good deal more profitable as theology than the first chapter of Genesis.” This view was confused he said and failed to distinguish between “a theological doctrine of creation and a scientific doctrine of origins.” “Natural science” he said “is concerned with the causal order of events as they actually happen and have happened in space and time. This, as it is traced backwards, brings us to certain primitive events which we may believe to have been the origin of life, or of the earth, or of the solar system or the stars. As to the nature and succession of these events it is doubtless true that the authority of such experts as Darwin is to be preferred to the author of Genesis.” But he goes on to make a telling point, “… theology is not interested primarily or chiefly in the question of temporal origins, even when it is stating its doctrine of creation. It is interested primarily and chiefly in the end or value of what has been created.”

Quick’s contribution to this question is a good example of the theologian’s contribution to the linking of life and society, of things as they are in themselves and how we engage with them and each other.

John Calvin’s commentary on Genesis, written at the time when astronomy was providing new knowledge of the universe, is instructive in helping to apply this distinction. He lived at a time in the early part of the sixteenth century when the structure of the universe was being described in new ways.

Calvin was in no doubt that Moses had used descriptions of the natural world that were consistent with both the worldview of his time and the rudimentary appearance of things. The cosmology of the book of Genesis is one of a terrestrial zone or layer that has been inserted as a dividing layer between the waters beneath the earth and the waters above the heavens. This, according to Calvin, “appears opposed to common sense, and quite incredible … to my mind, this is a certain principle, that nothing is here treated of but the visible form of the world. He who would learn astronomy, and other recondite arts, let him go elsewhere” (Commentary on Genesis, 1.6).

Calvin is wary of people who import a cosmology from a previous unscientific period into the core of Christian doctrine. “The assertion of some, that they embrace by faith what they have read concerning the waters above the heavens, notwithstanding their ignorance respecting them, is not in accordance with the design of Moses” (Commentary on Genesis, 1.6). Given that he was speaking into a faith/science debate as far as the insights of astronomy were with odds with cosmological conclusions from Scripture—which there can be no doubt that John Calvin considered authoritative—his praise for science and rejection of its critics invites us to see a parallel in the Young Earth Creation ideas that underlie the so called “creation science” and scientific thinking more broadly.

Moses makes two great luminaries; but astronomers prove, by conclusive reasons that the star of Saturn, which on account of its great distance, appears the least of all, is greater than the moon. Here lies the difference; Moses wrote in a popular style things which without instruction, all ordinary persons, endued with common sense, are able to understand; but astronomers investigate with great labour whatever the sagacity of the human mind can comprehend. Nevertheless, this study is not to be reprobated, nor this science to be condemned, because some frantic persons are wont boldly to reject whatever is unknown to them. For astronomy is not only pleasant, but also very useful to be known: it cannot be denied that this art unfolds the admirable wisdom of God. Wherefore, as ingenious men are to be honoured who have expended useful labour on this subject, so they who have leisure and capacity ought not to neglect this kind of exercise. (Commentary on Genesis, 1.16).

Bishop Lee Rayfield is a colleague of mine formerly the Bishop of Swindon in the Church of England and who was, by his professional training, an immunologist. Like other Anglican bishops he wears a pectoral cross as a symbol both of his office as a bishop and of his calling as a disciple of Christ. These are his reflections on what he chose as his bishops’ cross:

One of the distinctive symbols of office for a bishop is a pectoral cross. Quite often bishops will choose a design that reflects a significant aspect of their spiritual journey and convictions about God. When I was consecrated a bishop in 2005, I chose the emblem of The Society of Ordained Scientists—a cross surrounded by a “halo” of DNA, the physical building block of life. The cross of the Ordained Scientists reflects my own journey of faith as a biological scientist and my conviction that scientific insights and Christian belief are meant to be companions not competitors.

Are we able to look at the model of the DNA molecule, the physical building block of life (that stands in front of the pulpit) as a metaphor for faith and science? Can there in fact be two strands of truth inevitably needing each other to make the whole or are we looking a situation that will always be even at its best a tangled mess? Many of us will conclude the former and find our science and our faith mutually enriched by what they tell us about the world and ourselves.

Bishop Rowan Williams gives us a very thoughtful reflection that I will read as a conclusion to my words this afternoon.

Jesus is about discovering the world is more than you ever suspected, and so that you yourself are more than you suspected. The joy of the resurrection has a unique place in Christian faith and imagination because this event breaks open the shell of the world we thought we knew and projects us into the new and mysterious realm in which victorious mercy and inexhaustible love make the rules. And because it is the revelation of something utterly basic about reality itself, it is a joy that cannot just be at the mercy of passing feelings. It roots itself in the heart and remains as a foundation of everything else. The Christian is not therefore the person who has accepted a particular set of theories about the universe but the person who lives by the power of the joy that is laid bare in the event of the resurrection of Jesus (Sermon at Canterbury Cathedral, Easter 2011).