Originally published in The Melbourne Anglican.

ISCAST fellow the Reverend Dr Robert Brennan is training manager and teaches theology at the Indigenous Wontulp-Bi-Buya College in Cairns, a college that provides theological tertiary education to First Nations people who would otherwise struggle to access it.

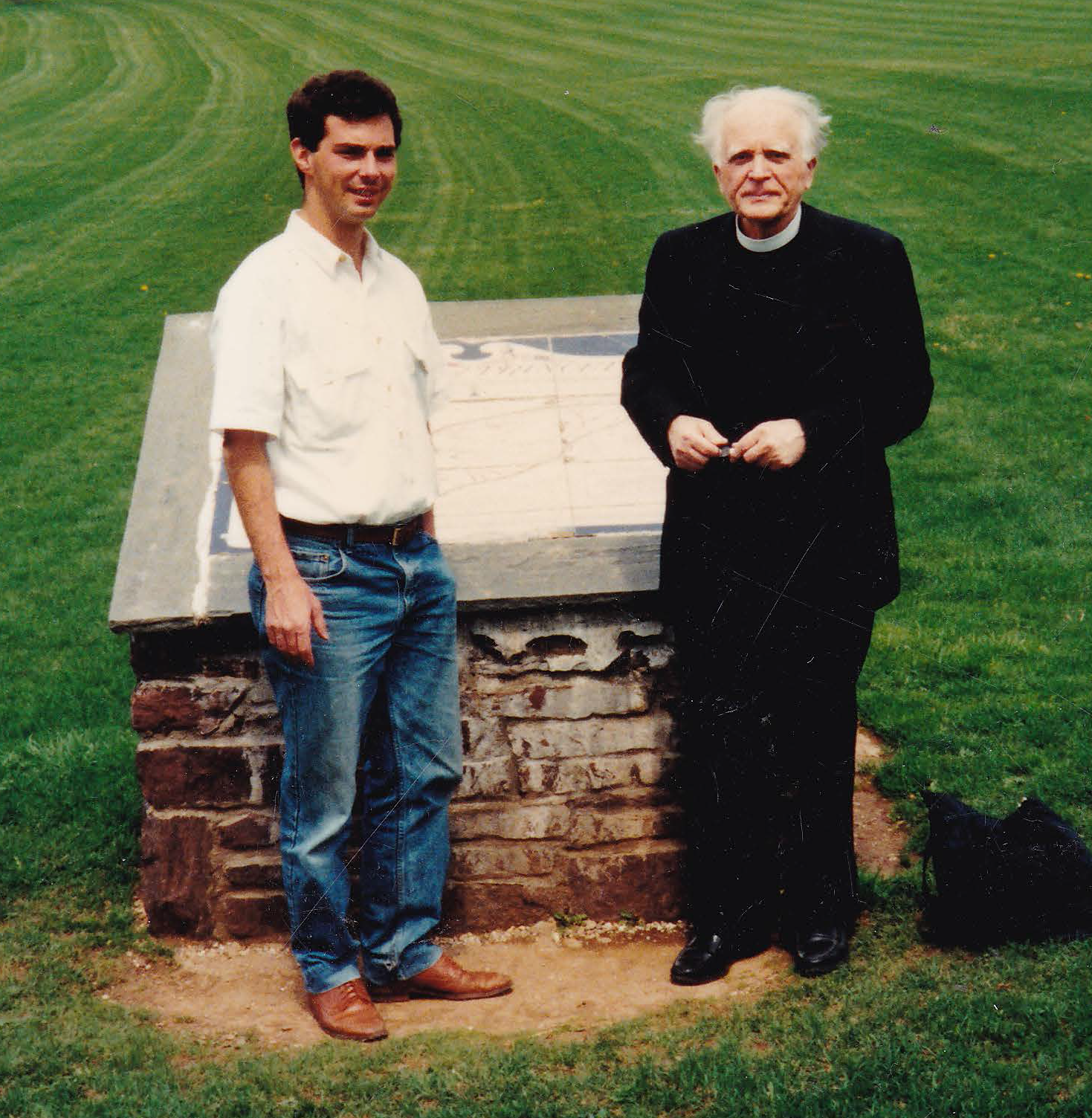

With interests in the historical development of the relationship between theology and science, he has written Describing the Hand of God: Divine Agency and Augustinian Obstacles to the Dialogue between Theology and Science.

With a background in industrial physics, how did Robert come to be a Uniting Church minister teaching theology to Indigenous people? In this article, Robert reflects on his journey through science and theology.

I grew up loving science and looking to the heavens. It seemed natural to pursue physics to explain the wonder and beauty of creation. While learning science, I also grew in my understanding of the love and power of God.

Practical science entranced me. As a medical physicist, I specialised in ergonomics: designing tools and processes to fit human capabilities. Too often the tools and processes people use at work make people inefficient, error prone and put them at risk. I worked to improve people’s safety and health.

In this field, it was always people’s attitude that was the key to making them safer and their work better. We humans retain habits even when they are harmful. In working for better ergonomics, it often seemed impossible to break those habits and instil change. One would think it would be easy to offer people ways to work that did not wreck their hearing or health. It was not! People often stick with the familiar even when it is dangerous, hard or kills them slowly.

Ergonomics required flexible thinking, passionate care and unimaginable persistence to make change. It is interesting that this parallels pastoral work. In ministry too, people can take a lot of convincing to not wreck their lives by persisting with old habits.

I felt a sense of call to ministry from my late teens, but it seems God thought I needed to learn how the world worked in industry before going down the pastoral track. A lot of people could not understand how I could be a scientist and a person of faith. And, there were science-faith issues that I hoped could be resolved.

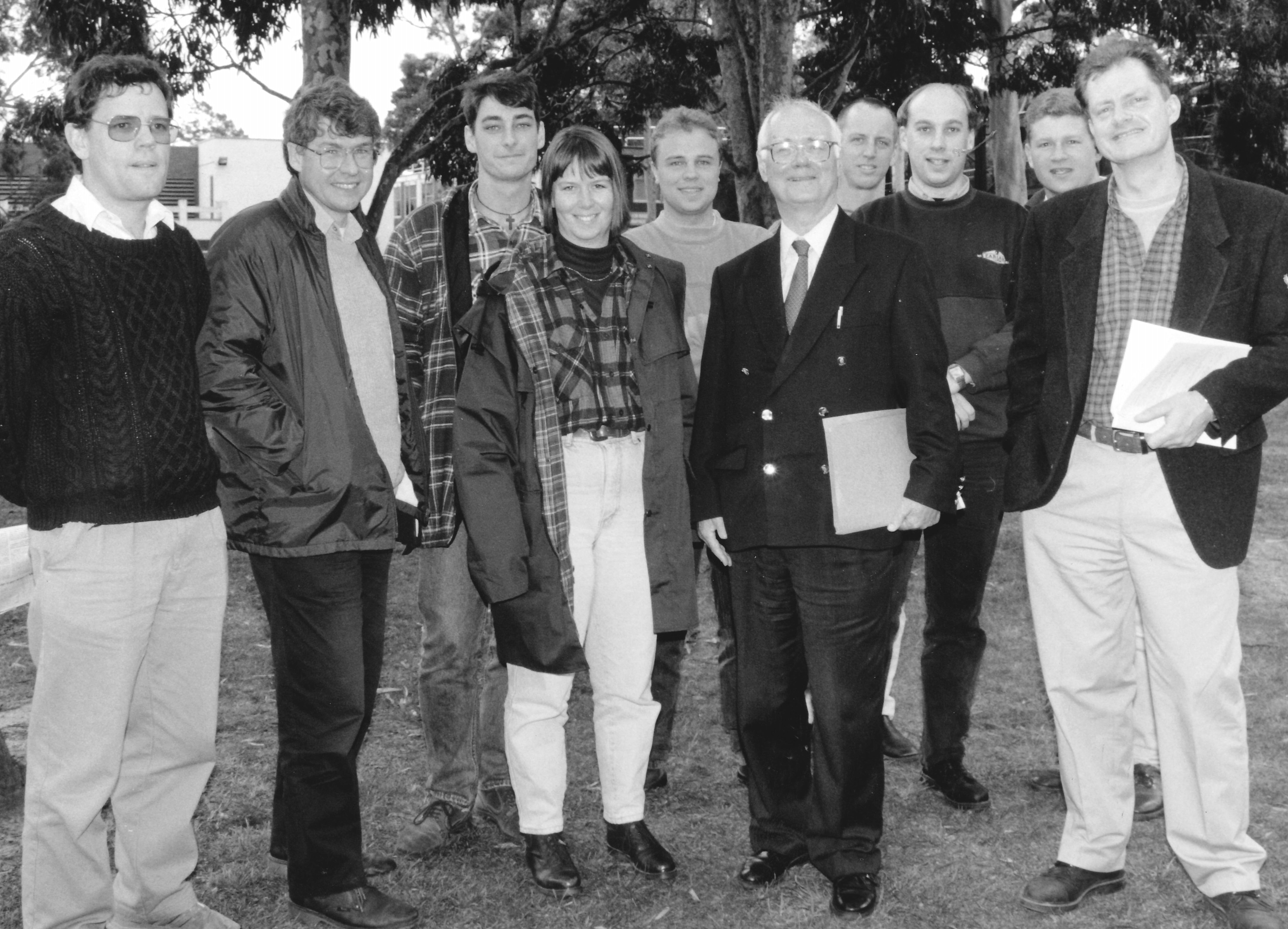

In my theological degree, I realised that I had been missing out on studying history. I absorbed both theology and history, and could not read enough. I also discovered that scientific training in careful logical thought is invaluable to good theological thinking.

But my earlier questions about the relationship of science to faith continued unanswered. My PhD was an opportunity to understand how the Holy Spirit’s work in people and the world influences science’s understanding of the world. Key leaders developing early modern science assumed the Holy Spirit’s work would reflect God’s perfection. They discovered, however that nature does not always reflect this. This led Darwin and others to conclude God did not act: “It couldn’t be God’s work.” This forced an all-or-nothing false dichotomy for important thinkers, a dichotomy that was shown to be based on an incomplete understanding of how God’s Spirit works in humans and nature.

A call to teach is part of my sense of a call to ministry. So, with a newly minted PhD, I started to look for a teaching post. But I always seemed to be the bridesmaid and never the bride. As I was about to give up a couple of good scientist friends encouraged me. “Keep trying, God has a place for you,” they said. Then a position at an ecumenical theological college in Cairns came up. It was the last place on earth I thought I would go. But I’ve been here for eight years now! It seems that God did have a place for me.

Indigenous communities need leaders and ministers, but Indigenous students have difficulty getting into and through mainstream theological training. Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are denied the opportunity to do tertiary study. Fortunately, at Wontulp-Bi-Buya College in Cairns, Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islanders can receive theological training.

The college is culturally appropriate. This means working within language limitations. It means allowing people to take time out to grieve and follow cultural practices without question. At other colleges students must make a case for every extension, these are not automatically given. Part of being culturally appropriate is to make those allowances. Then we see Indigenous men and women appointed to leadership positions. One of the high points of last year was seeing one of my students ordained by the Archbishop of Canterbury during a visit to Cairns.

I ask myself, “Why am I here at Wontulp-Bi-Buya?” and find three answers.

First, to persist for change in a seemingly impossible situation. Many of my students live in the poorest communities, too many have been told “You cannot do this”. Too many have been denied hope for generations. In Christ we have hope! But it takes much courage and endurance to hold up that light. I have a lot of experience with that.

Secondly, to learn to seek God’s strength every day. But this is nothing compared with the strength my students need, as they face poverty, family violence, alcohol and drugs, sexual abuse, systemic injustices and racism.

And, thirdly, to meet the needs of our theologically conservative students. It is good to have someone teaching who is theologically conservative, but mentally flexible enough to work with the interesting and diverse ways Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders think about theology from their own cultural perspective.

However, there is another issue that is becoming clearer to me around many of my Indigenous students’ relationship with science and religion.

Highly respected historians Peter Harrison and Stephen Gaukroger, and theologian John Milbank, have recently described how scientific reasoning came to dominate European cultural and racial thought in the late 19th century. Notably, this was contemporary with the worst excesses and violence of our colonial period.

I am tempted to link the dominant, often-unquestioned dogma “it is scientific therefore true,” with persistent structural racism. Structural racism is where a dominant culture assumes without question that their way of thinking and solving problems is the only or the best way to think. This could explain why many of the Indigenous people I work with have a deep distrust of science, and accept the conflict narrative that science opposes Christianity. More worryingly, others associate scientific reasoning as being the rationale for generations of abuse: including segregation into reserves, forced assimilation, and stories of unethical experimentation on their people.

To counter this, there is a recent move towards what has been called decolonisation. I am not sure that the term is helpful as it lumps too many ideas together. Nevertheless, it helps to actively question the stories that “everyone knows” about the relationship between science and religion. Quite possibly, this is part of why I need to continue where I am.