Christians and Nature

The Promised Land that Abram and Lot entered thousands of years ago was a land flowing with milk and honey. It was what the Jewish ecologist, Daniel Hillel, calls the Pastoral Domain and what we foresters call “Open Woodland”—essentially pasture dotted with trees.

When the Israelites invaded the land in about 1,200 BC, they found that the Philistines had beaten them to it (Joshua 1:19) and the only land available was in the hills, what Hillel calls the “Rainfed Domain”. This is reflected in the promises that God made to the Israelites:

Then I will send rain on your land in its season, both autumn and spring rains, so that you may gather in your grain, new wine and olive oil. (Deuteronomy 11:14; see also Leviticus 26:4; Deuteronomy 28:12; Jeremiah 5:24).

The Rainfed Domain was heavily forested, and there was little room available for settlement (Joshua7:15-18). They had to adapt to this new environment and, essentially it pitted them against nature to clear the forests to make room and to protect themselves from the wild animals. Thus we read about David, the shepherd, driving off wildlife to protect the sheep (1 Samuel 17:34,35) and Isaiah promising that forested areas like Sharon would become grazing land for sheep and goats as a sign of blessing (Isaiah 65:9,10).

By Isaiah’s day (about 590 BC) the deforestation really started to bite. Much of this was due to land clearing for settlement, successive foreign invasions and the civil wars (e.g. David v Absalom, in which, of the 20,000 casualties, more were lost in the forest than were killed in the battle (2 Samuel 18: 6–8)), fires, timber harvesting (e.g. Solomon and his building program (1 Kings 5.)), but mostly grazing. Scholars are unanimous that sheep and goats were (and are) the “ecological dominant”.

Scripture provides two glimpses of what the Rainfed Domain would have been like before humans took over: Psalm 104 and Job 38 – 41. Psalm 104 exults in God the Creator, and then marvels at that creation, recognising both the rural environment and the wilderness within that domain as being equally God’s.

The Job passage approaches wilderness from another perspective, with a bewildered Job beseeching God to end the divine silence. In chapter 38 God speaks, not with an explanation, but with a guided tour of nature. Here the majesty of God is seen not in things agricultural—the things useful to humans, but in an alien wilderness, the creatures there and the forces in play.

By Jesus’ day, not much of this remained and the animals Jesus talks about in his teaching were the ecological criminals, sheep and goats. However, the deforestation in Palestine continued and the Roman Emperor, Hadrian, in about 120 AD, had forest areas demarcated to ensure they were preserved. Many of these markers are still there today although the forests they were meant to protect have long-since gone.

Looking at Jesus’ ministry, he says nothing about these things. He refers mostly to the Jewish farming practices and the agricultural ecology the farmers had inherited, and he draws on these to make his points about God the loving heavenly father and our dependence on God. He does not speak about nature as it was or about the original flora and fauna (however much we might wish that he did—something about goats would have been nice!).

Today many of us are deeply concerned about nature and humanity’s impact on it (deforestation, climate change, salinity, and so on). And so we trawl through scripture to find some teaching that will give us a quintessentially Christian answer to the problems, perhaps a magic wand or a silver bullet; or a stick with which we can beat non-Christians over the head and tell them: “I told you so!” or “See! Christians are right, and you are wrong!”

But Jesus did not give that to us. One can derive statements to say that God’s creation is important but nothing to say what we should therefore do or what takes priority. Is feeding the poor more important than protecting biodiversity (assuming that this is an ‘either-or’ question)? Jesus doesn’t say. Does Jesus’ silence mean that we should not be concerned about our impact; an impact that will affect not only us, but other people in other places and in other times (e.g. our grandchildren)?

As Paul says: “By no means!!” There are a lot of things we wish Jesus had spoken about (e.g. the abolition of slavery) but he didn’t. Each one of us in our sciences are opening up new areas of knowledge which bring us challenges that were unforeseen both in Jesus’ day or in ours not so long ago (the concept of biodiversity was only coined in 1968!). Each of these call on us to take responsibility for the impact of these sciences and work out what should be done.

I see that the lack of explicit direction in Scripture is a gift to us. Scripture is not a manual providing answers for every conundrum that we face. These are challenges for us to work out ourselves, with our community and not by running to Daddy every time we want someone to do our thinking for us. It is time we put on big persons’ pants and grew up!

The answers to the challenges we face will change from age to age and as humanity’s demands on nature change, as our scientific knowledge changes and as nature responds or reacts to what we do. This is not a simple process and there are no magic wands. If anyone tries to say that they have ‘The Answer’, it is probably because they don’t know what the question is.

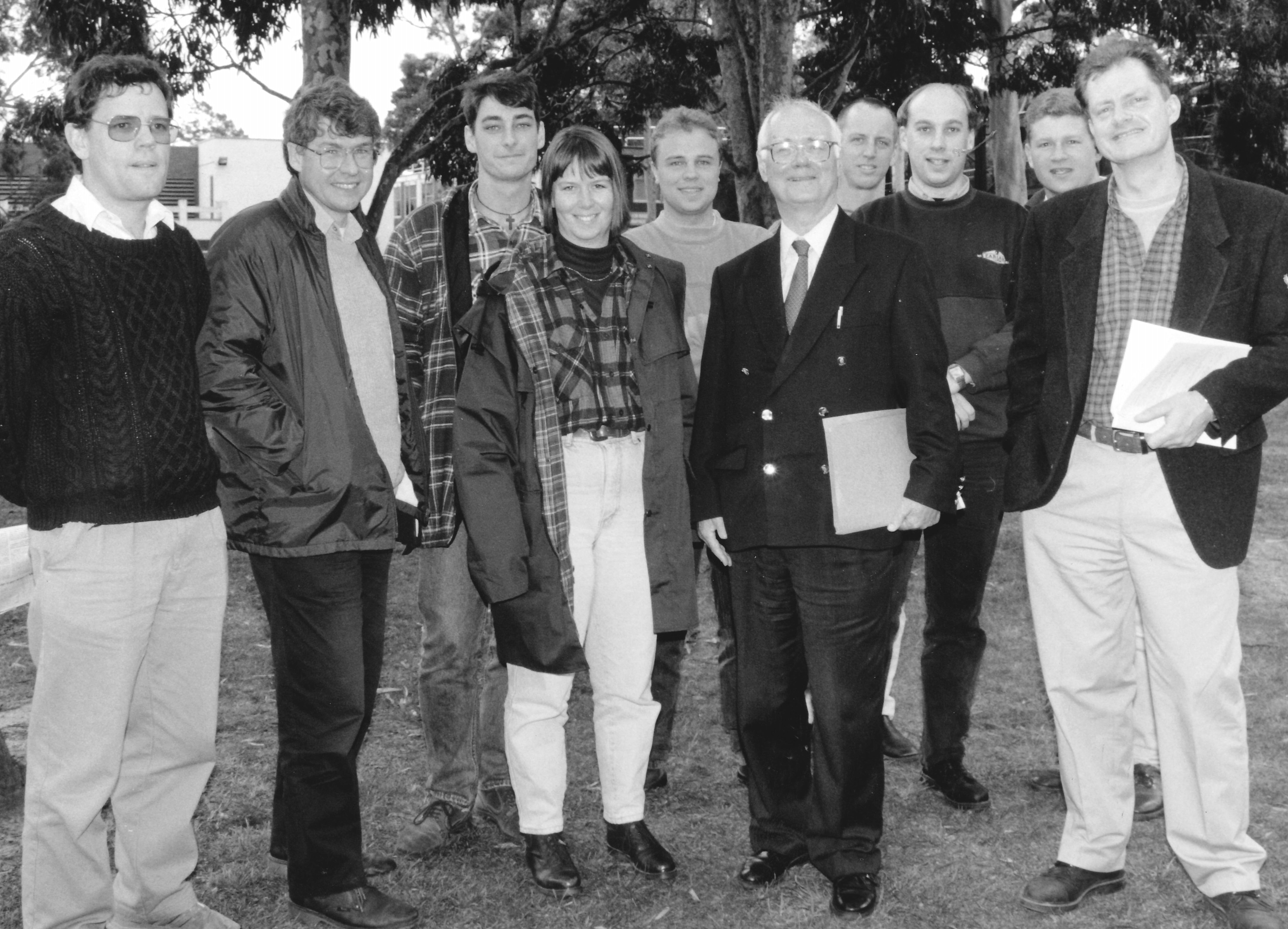

It is with this in mind that I look to our ISCASTian mandate. As Christian representatives of Australia’s scientific and professional elite, we have Jesus’ challenge: “of those to whom much has been given, much is expected”. We do not work through these issues by ourselves but with our colleagues (both Christian and non-Christian) within the context of our society and its struggles with the issues.

We also bring to the conversation an understanding of a loving, proactive God who loves not only us but the whole of creation, we also have the guidance of the Holy Spirit in our lives as we struggle with these things, and we do have the fellowship with each other as we struggle with the issues our sciences create.

My experience in ISCAST is that it is not in us persuading people that we are right that advances the conversation, it is how we conduct ourselves:

In your hearts revere Christ as Lord. Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks the reason for the hope you have. But do this with gentleness and respect. (1 Peter 3:15)

In the words of our Core Values, we offer our insights with “firm humility” and so provide a contribution which, without it, society’s response will be incomplete.

In an age when people are wondering whether Christianity and the church are relevant, the ball is in our court to demonstrate that it is. Not by providing pre-digested, religion-specific answers but by working incarnationally within our society as it too struggles with these issues.

There is no road map for these things and we need to acknowledge that we are feeling our way. It would be nice to be able to say: “Here is the way, walk ye in it!”. But, in God’s wisdom, that has not been given to us.

God grant us as individuals and as ISCAST and the Church the wisdom and intelligence guided by the Holy Spirit to work through these difficult situations as they change over space and time, working with our professional colleagues to help make society more just, more responsible and closer to the kingdom of God.