Enhancing humanity with technology is increasingly common. But is it a good thing? ISCAST Fellow Victoria Lorrimar explores the Christian response to human enhancement.

Originally published in The Melbourne Anglican.

ISCAST opinion articles invite writers to share their perspectives on various science–faith topics to generate a constructive conversation. While ISCAST is committed to orthodox Christian faith and mainstream science, our writers may come from a range of positions and do not represent ISCAST.

What might humans become with technology?

The prospect of enhancing human capacities through technology has long been a theme in science fiction, and we are seeing more and more real-world implementation. But how should Christians think about human technological enhancement?

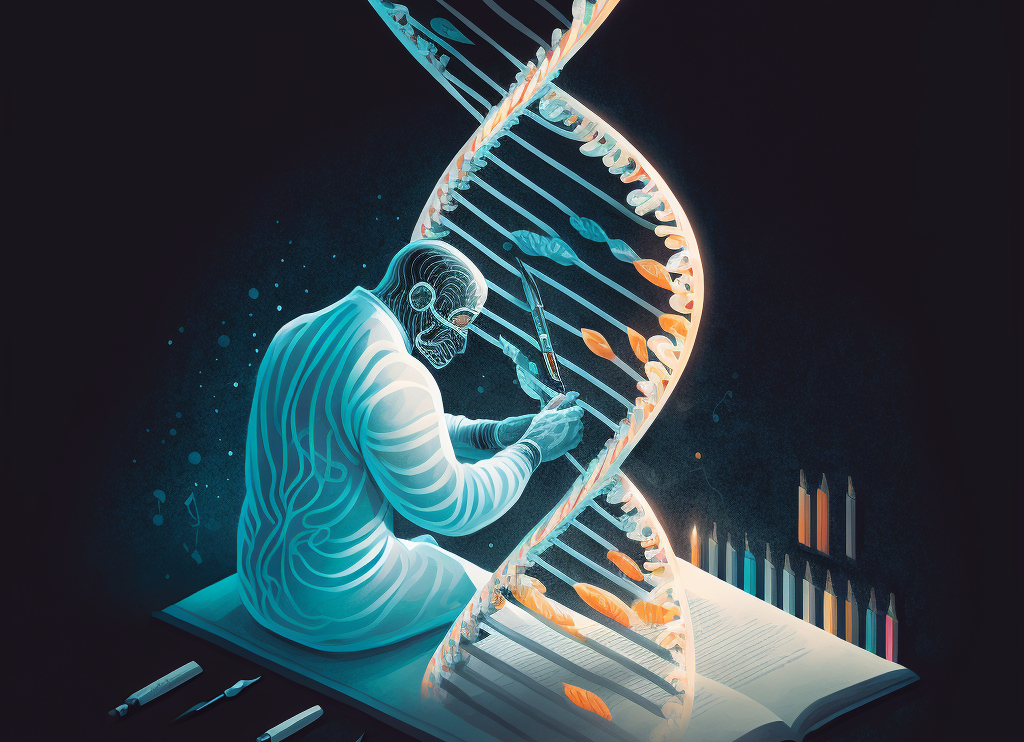

Christians rejecting particular technologies as “playing God” has a long history, often in the realm of medicine or agriculture. This is particularly true of technologies that might alter human characteristics in some way. It has been seen as an overstepping of the boundary between Creator and creation. For example, a 2016 North American study showed a stronger rejection of three hypothetical enhancements among individuals with higher religious commitment, who were predominantly Christian, than those with lower religious commitment or none. These suggested enhancements were gene editing to reduce disease risk, neural implants to improve cognitive abilities, and synthetic blood to improve physical abilities. Respondents who answered in the negative judged these as “meddling with nature” and “cross[ing] a line we should not cross”. Revealing more general perceptions, Christianity Today published the results with the sensationalist headline “Christians to Science: Leave Our Bodies How God Made Them”.

Often the charge of “playing God” is rooted in fear, as new technologies shift the boundary between what we accept as given and what we can affect through our own action. When something new crosses that boundary into the realm of our own capability, we can be wary.

But what if we are too hasty in dismissing enhancement technologies, or technology more generally, as playing God? Imbued as we are with imaginations, ingenuity, and intellects, might such technologies be a legitimate aspect of human creativity?

Often the charge of “playing God” is rooted in fear, as new technologies shift the boundary between what we accept as given and what we can affect through our own action.

There are different kinds of creative acts. Two different types of creation are described in the Hebrew Scriptures in particular.

The main word for “create” in Hebrew is bara, used in the opening line of Genesis: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth”. This verb appears around 50 times in the Old Testament, and the most important thing to know about it is that the subject is always God. So, God is the one that is doing the creating. If we consider the stuff that is being created, then we have a list of things that include the cosmos, people, specific groups of people, geographical features, creatures, and phenomena. It’s also the verb that is used when David implores God to “create in him a pure heart” in Psalm 56.

So it’s pretty clear from the usage in the Old Testament that bara refers to God alone. It is an act that is uniquely divine and does not cross the divide between God and humanity. But this isn’t the only Hebrew word for “create”—we also have the verb yatsar, which is used in Genesis 2 to describe God’s fashioning of the human from the earth and the forming of other animals.

What’s especially interesting about yatsar is that it doesn’t just apply to God but is used to speak of human action as well, for instance in Isaiah 29:16 or Habbakuk 2:18. The term and its cognates invoke strong connotations of art and craftsmanship, referring to the work of the woodcarver, and of the potter. This is likely connected to the “lumps of clay” that made up the raw materials in Genesis 2:7.

With this verb, we build up an understanding of God as an artist, beginning a project in which we are graciously allowed to collaborate. In his book Making Good theologian Trevor Hart sums up this understanding, saying that at some key points in the story of God’s creative fashioning of a world fit for his own indwelling: “divine artistry actively solicits a corresponding creaturely creativity, apart from which the project cannot and will not come to fruition”.

With this verb, we build up an understanding of God as an artist, beginning a project in which we are graciously allowed to collaborate.

We tend to think of human creativity mainly in terms of art, but human making is not restricted to the artistic sphere. Through the modern period art and craftsmanship became increasingly separate from science and technology, but all of these endeavours have their place in human creativity.

If we can frame technological activity as within the scope of humanity’s created purpose, then our questions around human enhancement technology in particular shift. No longer is everything ruled off-limits from the outset as “playing God”.

Instead, Christians should practice discernment. Technological proposals move into the realm of ethics, as we weigh up the motives and outcomes of particular technologies. The theological questions are not concentrated on whether such technologies are permissible wholesale, but can instead explore the way in which such technologies are perceived in the broader culture, and the underpinning assumptions they reveal. Many techno-futurist visions portray technology as saviour, whether in science-fiction or the real world. They promote particular understandings of what makes for a good life—longevity, intelligence, efficiency—that may not always line up with a Christian understanding of flourishing, that should prioritise justice, equality, and mercy.

Christian theology has something valuable to contribute when it comes to an understanding of the human life and what it might look like to flourish. In Christian Ethics in a Technological Age theologian Brian Brock reminds us that the Christian story, “reveals as good news human ingenuity and the richness of creation’s given material order, insisting that the two can come together in the creation of good and beneficial techniques and mechanical artefacts”. In making this statement we affirm two basic claims: that human collaboration with God’s work can compete with mixed motives in a world that is still being redeemed, but also that we are freed from “the burden of ensuring that God triumphs over the powers of this age”.

There may be many aspects of technological enhancement that Christians will ultimately discern to be unwise, but faith ought not prevent us from being a part of the dialogue concerning technological possibilities. While there are certain acts of creation that God alone is capable of, the fact that we are invited into the overall project of ongoing creation gives us a sense of responsibility. We live out our lives within the tension of receiving our created life as a gift, but also understanding it to be a task requiring a response from us.