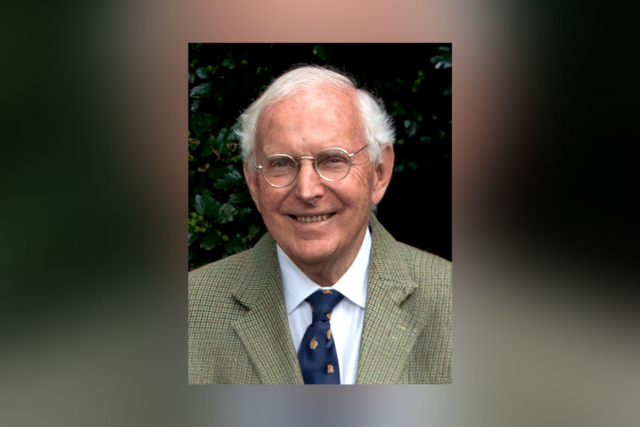

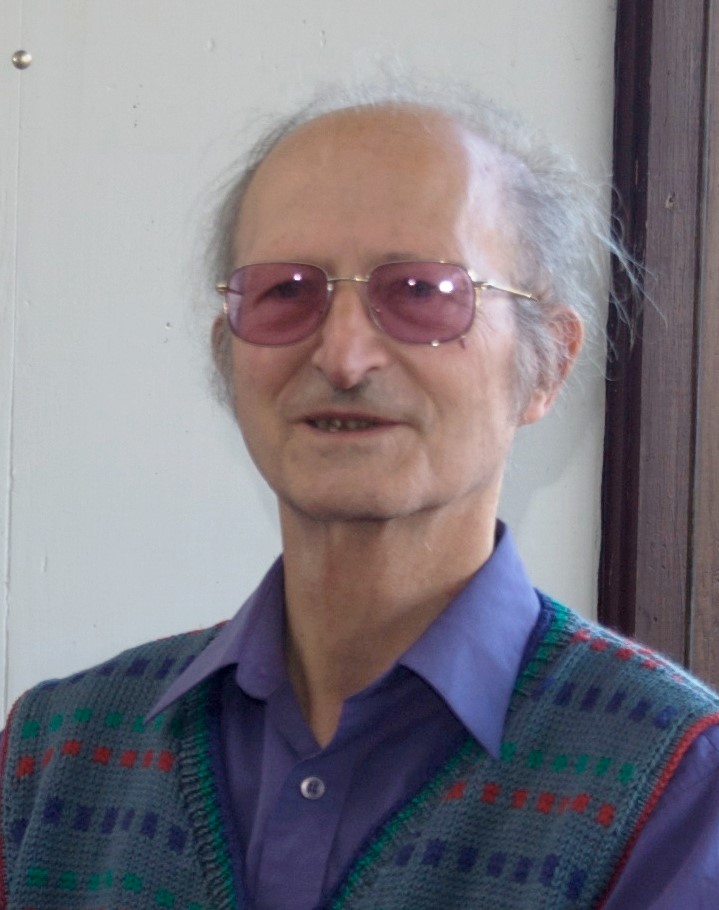

Geoff Nutting, a friend and colleague to many ISCASTians passed away in August 2016. This tribute is adapted from the funeral eulogy prepared by Geoff’s widow, Solway, and his son David and daughter Bridget. The afterword was prepared by Emeritus Professor John Pilbrow who first met Geoff 50 years ago.

Dr GEOFFREY HOWARD NUTTING[1]

14/10/1936 – 25/08/2017

After a life that spanned three continents and three different careers, Geoff died of cancer in Castlemaine, Australia, with members of his family at his bedside.

Born in Wolverhampton, UK, he attended Wolverhampton Grammar School for his secondary education and progressed to Durham University and later Oxford. He was the first in his family to gain tertiary qualifications: BA in Music from Durham (where his college was St John’s), and Diploma in Theology from Oxford.

It was through these interests of music and theology that he met Julia Hale. They married in London in 1960, and not long afterwards Geoff took up a position in the Music Department of the new University of Nigeria. In terms of his professional work, he felt the period in Nigeria (1961–1966) was the best time of his life. There he was free to lecture in Religious Studies and in History as well as Musicology. But civil war, the Biafran War, brought this treasured time to an end, and Geoff and Julia, son David and daughter Bridget, began a new life on his third continent, Australia.

Geoff came to Monash University in 1967 as a Lecturer in Music. He found it very different from his time in Africa; no longer was he able to offer theology classes at the University, and the Australian culture and Australian style of English took a lot of getting used to. (Twenty years on, acceding to the demands of mateship, he was to choose to be known as Geoff rather than Geoffrey). At Monash, after three years and a promotion, he was unconvinced that musicology was right for him. He took time off, and reinvented himself as a Rare Book Cataloguer in the Monash University Library.

During 1988 he undertook formal training in Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE) in order to be a chaplain serving the mentally ill. He worked at Mont Park Hospital in Melbourne, and later informally in the Acute Psychiatric ward of Bendigo Hospital. There he carried his violin with him, ready to play Bach Bourrees or favourites like Danny Boy. He saw it as ‘waging peace’, giving his attention to each patient so s/he felt accepted and honoured just as s/he is. He was also researching medieval Western mystical theology, which led him to discover the Enneagram of Personality, and this became the roadmap for his understanding of how relationships flow easily for some people, and more turbulently for others.

Playing chamber music and listening to the best recordings through hi-fidelity sound equipment were a constant source of comfort to Geoff. Through music, and also the Enneagram, he met his second wife Solway. They began married life in 1996, living in Castlemaine, Victoria, which had already been his home for two years. ‘He was not a lofty intellectual, but a warm human being’, as a newly discovered English cousin described him. Geoff is remembered by his family for his many special qualities and gifts, in particular his gentleness, compassion, sense of justice and integrity. And he had a special love for dogs, communing effortlessly with his own and with those he met on his walks.

The Enneagram locates a person’s temperament as one of nine interconnected types, according to the value they hold most dear. In Geoff’s case, his highest goal was truth; at times his words could appear confronting to the unprepared! He put much valuable energy into using his understanding of each Enneagram type and its satellite positions, both in his personal relationships and in teaching people about connecting with others. Although his preferred mode was to work with individuals, he made a special mark on many in a larger community sense, through playing in music groups, preaching at church, advocating for just treatment of individuals, delivering papers at conferences, and writing for organisations.

His book, launched in 2011 and based on the thesis that earned him a Doctorate of Ministry Studies, was entitled On Becoming More Open to Others in God: Asperger Syndrome and the Enneagram. Largely autobiographical, in it he tells of his encounters with others from four different perspectives: historical, psychological, spiritual and the Enneagram. “You are your relationships” was his watchword.

Always quick to spot the flaw in an argument or the point of view others have overlooked, Geoff had a sharp and analytical mind. He expressed his convictions with strength and clarity, and with a directness that encouraged others to reflect more deeply on the issues discussed. His writings were meticulously crafted, revised again and again. He owned the description ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’, saying he had sought the diagnosis for research purposes. This led him into the field of research into Autism, to which he contributed Enneagram insights, while calling for interactions between professional and ‘client’ as human beings, not labels.

In recent years he contributed to a professional body concerned more with science than the humanities of all his previous experience. This was ISCAST, the Institute for the Study of Christianity in an Age of Science and Technology.

Geoff’s involvement with ISCAST is best described in his own words:-

“ISCAST has been, over almost all my final decade, my prime professional forum and network. Religious Studies and Philosophy had, from undergraduate days, been my passion. Admitted as Associate in 2009, and in 2011 elected a Fellow, I contributed papers to seven ISCAST gatherings: Biennial National COSAC conferences, and in the intervening years Victorian State Seminars. In all of this I have valued greatly the inspiration, support and affirmation of the current President, Associate Professor Alan Gijsbers.

With the exception of musical acoustics, which I had taught in an early lecturing career as musicologist, the scientific mindset, with its stress on the measurable, was to me a novel environment. For forty years long, with almost zero science taught in my 1950s English grammar schooling, I had addressed myself strictly to Humanities audiences. ISCAST was an invitation to a broad new vision of existence-in-creation.”

Geoff attended some seven major ISCAST events, the last being COSAC2015 [Conference on Science and Christianity] where he and Solway presented The Castlemaine Story, a community effort to care for the environment in the light of Climate Change and Global Warming.

Knowing his disease was terminal, Geoff yet hoped to write a second book, which might initially have been called D’you Hear What I Said? But the process was too daunting. In spite of his illness he remained committed to academia, and few who knew him through his articles and letters had any idea he would stop writing so soon.

He lived simply, almost monastically. To everything he would apply Occam’s Razor, going for simplicity, not multiplicity. A faithful churchgoer, he was a lay preacher and lay reader, and could read aloud biblical texts at sight with full meaning and conviction.

Above all, he searched for the truth as he saw it, which led him at the ripe age of eighty, to switch his allegiance from the Anglican to the Catholic Church, a transition and dedication which he had delayed for more than half a lifetime.

Geoff left this world, reconciled in his relationships, and at peace.

It is fitting to end with this tribute from ISCAST President, Alan Gijsbers, that captures the essence of a very special person:-

“Geoff was an unusual character of great heart, who vigorously pursued the truth as he saw it and sought to serve his Master faithfully and well. His struggle to understand himself was very open and sometimes quite fraught but this did not stop him from ministering to others out of his own struggles. Resting in peace has a particular resonance with him I think.”

AFTERWARD by Emeritus Professor John Pilbrow

I first met Geoff 50 years ago not long after he joined the staff of the Music Department at Monash University, and from time to time we both attended meetings of an informal Staff Christian Group. In 1973, when his Anglican Parish held a Mission, I was invited to lead a discussion in his home. Over the next decade or so, as Geoff was dealing with what was eventually diagnosed as Bipolar Disorder, he moved from the Music Department to the Main Library as a Rare Book Cataloguer. During a period of recovery, in 1980 Geoff participated in a Student Bible Study also attended by our eldest son. It was not until the late 1980’s before Geoff moved into Mental Health Chaplaincy, that we began to meet more frequently at the weekly Anglican Communion Service in the Monash Chapel. But then it was almost another 20 years before we met again. We were sorry to have lost touch and often wondered how he was getting along. It so happened that in May 2008, Susan and I stayed in Castlemaine overnight and attended the local Anglican Church. There we were delighted to meet up again with Geoff in what was then his local Parish! As we caught up with the years, Geoff learned about ISCAST, eventually becoming a Fellow. Through Geoff, I received an invitation to come back to Castlemaine in October 2010 to present a lecture, Making Sense of Faith in the Age of Science and Technology, to a combined Churches event attended by about a 100 people. Some came from as far away as Bendigo.

On subsequent visits to the Castlemaine area, Susan and I always made a point of visiting Geoff and Solway, and enjoying their friendship and fellowship.

Geoff’s journey was not everybody’s journey. In working through the issues raised by the Bipolar diagnosis with help from Psychiatrists, Geoff also acknowledged his debt to the Monks at Tarrawarra Abbey. He brought together these experiences, along with his time as a Mental Health Chaplain, into what became eventually a doctoral thesis, demonstrating a very deep level of self-awareness. The tribute above by Alan Gijsbers, from the perspective of both a Christian and a Physician, well captures the essence of Geoff’s character

Whilst ISCAST has in many ways been a de facto Faith-Science organisation, it is worth reflecting for a moment on the wider perspective contained in the full title – Institute for the Study of Christianity in an Age of Science and Technology. This implies that issues should go beyond simply the faith-science interface, reflecting on them in the light of the age in which we find ourselves. People such as Geoff have challenged us to live up to that wider mandate, and to move out of our comfort zones. Geoff also welcomed and saw the importance of the recent ISCAST principle of providing a ‘safe theological space’ in which to engage in the key issues of our day.

An unforgettable character, Geoff will be missed by friends and acquaintances alike for the challenges he brought to our thinking.

[1] This tribute is adapted from the funeral eulogy prepared by Geoff’s widow, Solway, and his son David and daughter Bridget. The afterword was prepared by Emeritus Professor John Pilbrow who first met Geoff 50 years ago.